V - THE EFFECTIVE USE OF LIFE INSURANCE Independent Research Project

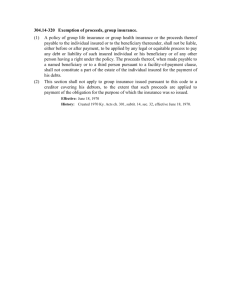

advertisement