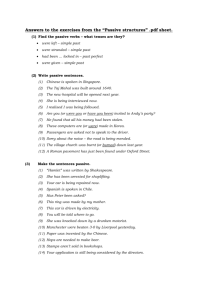

ARTICLE C T L

advertisement