R CHALLENGE ISING TO THE H

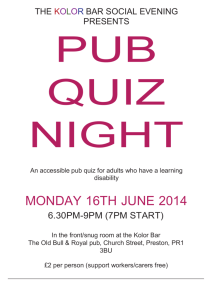

advertisement