Causal Effects of Schooling on Health Belief ⇤ Prabal K. De

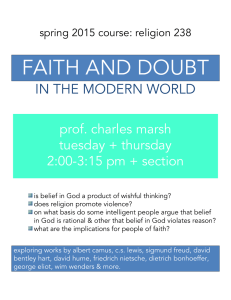

advertisement

Causal Effects of Schooling on Health Belief⇤ Prabal K. De† December 20, 2014 Abstract Health beliefs, or individual perceptions on the effects of health actions and behavior have been shown to be an important driver of health behaviors and outcomes. Unfortunately, very little research exists on the determinants of health beliefs. Though higher educational attainment in terms of formal schooling should in principle lead to better health beliefs, the relationship is confounded by omitted variables like motivation that may positively affect both education and health knowledge acquisition. In this paper I try to tackle two problems. I use data from India, a country characterized by tremendous variations in upper secondary educational achievements that allows me to see the effects of an extra year of upper secondary schooling on health beliefs. Additionally, I use arguably exogenous variations in age at menarche combined with poor sanitation facilities in schools in India to create a new instrument for schooling to control for the endogeneity. My results show that while education improves certain health beliefs such as reproductive health beliefs and AIDS awareness, it has no impact on other types of health belief like environmental health among ever-married women of age 15-49. Keywords: Health belief, Education, Instrumental Variable JEL Codes: : I12; J16; O12 ⇤I am grateful to Punit Arora, Marta Bengoa, Maria Binz-Scharf, Kevin Foster, Kameshwari Shankar and seminar participants at the New York State Economic Association Annual Meeting for many helpful comments. All remaining errors are mine. † Department of Economics and Business, The City College of New York and The Graduate Center. 160 Convent Avenue, New York, NY 10031, Phone:+1-212-6506208, Email:pde@ccny.cuny.edu 1 1 Introduction Health beliefs are defined as individual perceptions on how various health actions would increase or decrease the likelihood of health outcomes, with respect to both personal and public health. For example, whether or not a person is aware of the existence a global disease like AIDS and the ways it gets transmitted may affect his various health behaviors, influencing both individual and communal health outcome. Even though policy makers are ultimately interested in health outcomes, learning about health beliefs and changing such beliefs may be equally important. Question is: What determines health beliefs? Insights from human capital theory and health production function suggests that educational attainment should lead to better health beliefs. This paper offers new insights in answering that question showing that in societies where both upper secondary education and beliefs on diseases are incomplete, schooling may play an important role in improving correct health beliefs.1 That educational attainment (completed schooling) is positively correlated with better health outcomes is well documented.2 However, there is no single channel through which the benefits of schooling works (Braveman et al., 2011). First, higher education may increase the probability of finding a job leading to higher income and consequently affording good healthcare. Second, education may positively affect both personal traits and social support. Third, education, particularly in countries where primary education is not universal and illiteracy is still pervasive, may lead to better health belief. I investigate the third link in the context of India, a middle-income country that ranks 163 among 223 countries in the world in terms of life expectancy at birth.3 Though there is a rich and 1 The recent (and ongoing at the time of writing this paper) Ebola crisis shows that this issue is not restricted to poor countries in Asia and Africa. For relatively new diseases, public health belief formation takes time and has far-reaching implications for health outcomes. 2 For example, in the United States, the average difference in (male) life expectancy between a college graduate and a high school dropout is 13 years. National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health (2012): figure 32. Globally, countries with higher schooling attainment also typically have higher life expectancy. 3 “India.” CIA World Factbook 2 growing body of research connecting health belief to health outcomes, there is little research on the determinants of health belief. Role of information and acquiring such information is emphasized in standard economic models as a key to finding the optimal economic behavior. Therefore, we want to know how individuals can obtain such information. Intuitively, education is a straightforward candidate variable - more schooling may help individuals learn more about diseases, their causes and effects. However, the role of education, typically captured by years of schooling, in promoting correct health belief is not obvious. UNESCO statistics suggest that more than 700 million of the world’s adult population are still not literate; two thirds of them women. It will be incorrect to assume that they have no source of information to form health beliefs. Public information campaigns work simultaneously with expansions of schooling. On the other hand, there are no obvious reasons why more formally educated individuals are likely to form correct beliefs on all dimensions of health.4 Moreover, schooling may affect one set of beliefs, but not others. For example, sex education in schools can enhance attending students’ belief on reproductive health and awareness on AIDS, but those students’ belief on environmental health may remain unchanged. To summarize, that more schooling may lead to better health beliefs is a testable hypothesis. This paper formally tests such a hypothesis and tries to establish the causal role that years of schooling plays in generating better health awareness and belief. Identifying the effects of education on outcome variables is a challenge, because educational choices are often endogenous. Even after controlling for many observed variables, there may remain omitted variables such as motivation, drive and other unobservable personal characteristics that may influence both education choice and the outcome variables. For example, a motivated (motivation being the unobserved variable) person may try to acquire both health knowledge and education more. So it may be the case that the personal trait is driving the result, not education per se. In this paper I have used the timing of the onset of menarche as an instrumental variable (IV) for Ib. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2102rank.html 4 India had the third-largest number of people living with HIV in the world at the end of 2013, according to the UN AIDS program, and it accounts for more than half of all AIDS-related deaths in the Asia-Pacific. 3 schooling. Though age at menarche has been used an instrumental variable in some other contexts, to my knowledge this is the first time it is being used as an instrument for schooling. In India, this instrument is relevant due to the unfortunate reality of school sanitation infrastructure in many parts of the country, particularly in rural areas. According to a 2008 report submitted to the Indian Parliament, more than 466,000 elementary schools did not have toilet facilities. However, lack of toilets in school is particularly problematic for young girls in their recent years after puberty. Attending school becomes more costly for them due to lack of safety and privacy. This leads to missing school and eventually dropout. Though I will discuss the data and econometric methods in details later in the paper, it is instructive to illustrate my basic instrumental variable strategy at the outset. Figure 1 plots average years of schooling against the range of ages at which first menstrual cycle occurred for a of group 15-49 years old women. It shows that average schooling increases moderately with age at menarche up to age 12, the global average, but beyond it, average year of schooling increases more sharply with later onset of puberty. Additionally, it shows that (unsurprisingly) there is a big gap between urban and rural schooling attainment, though the age-at-menarche-education relationship holds true for both urban and rural areas. This graph comes with the caveat that the relationship is likely to be more complex, as other variables may also drive education rendering the age at menarche an insignificant predictor. However, we will see that my instrument is indeed relevant in an econometric sense. Please insert Figure 1 Here I examine a variety of women’s health belief - questions regarding reproductive health, neonatal care and AIDS. The belief system is not trivial. For example, more than 40% of the married women surveyed in 2004 answered that they had not heard about AIDS. I find that educational attainment does play a positive and significant role in enhancing health belief. This is true after correcting for the endogeneity of education and controlling for a variety of candidate explanatory variables such 4 as religion, caste, urbanity and poverty. The main finding is that higher educational achievement generally improves some particular forms of health belief among ever-married women in India. Such improvements are observed in reproductive health belief and AIDS awareness. More schooling, however, does not seem to increase awareness on indoor pollution or men’s health. I hope to expand the existing literature on the relationship between education, health belief and health outcome. The first contribution is to document that education has a causal role to play in enhancing health belief. Secondly, my instrumentation strategy shows that infrastructure such as clean, safe toilets may be as important as teachers and school materials in promoting education for girls. Together, they have implications for both global education and health policy. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. I start with discussion of health belief model and its implications. Next I turn to exploring the link between school sanitation and education in India and elsewhere. Section 4 discusses the survey data, sample selection and estimation strategy. The following section presents and analyzes my main results. Section 6 and 7 present sensitivity analysis and main caveats respectively. The final section concludes with discussion of policy implications for my findings. 2 Importance of Health Beliefs and Role of Education According to the traditional health production model, individuals choose and accumulate health inputs like diet, exercise and care to produce healthy days that are both consumption and investment good (Grossman, 1972). Education or formal schooling has been used as an input to production of both health behavior and health outcome. Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2008) provides an excellent account of the role of education in promoting health behavior in the United States. Elsewhere, Jurges et al. (2011) show how expansion of education changed health behavior in West Germany. Alsan and Cutler (2013) found that exogenous expansions in girls’ schooling led to a reduction in 5 their unsafe sexual behavior. However, not all studies have found a positive and significant effect of education on health behavior and outcome. In a recent paper Braakmann (2011) found in the U.K. in the context of expansion of schooling in certain parts of the country no effect of education on various health related measures nor an effect on health related behavior, e.g., smoking, drinking or eating various types of food. Though traditional health production function does not formally include health beliefs, “Health Belief Models”, popular in the public health literature may help us understand the role health beliefs play. Health Belief Model (HBM) is a conceptual formulation to understand a wide array of both affirmative and negative individual actions. Rosenstock (1974) argued that for an individual to ‘behave’ appropriately to avoid a disease, she needs to believe (i) that she is susceptible to the disease, (ii) that the disease is likely to affect her life, and (iii) that taking certain actions can help moderate the severity of the disease, should it happen. Meta-studies on empirical evidence, which have been updated periodically, have largely found support for the model (Carpenter, 2010; Jones 2013). Therefore, correct belief leads to choice of better inputs leading to more productive output. Though formal schooling has been the most commonly used variable as a determinant of health outcomes despite its limitations like not controlling for the quality of schools and informal education, it has been never been to test as an explanatory variable for health beliefs. The determinants of health beliefs and relevant policy implications for HBM have large been restricted to the design of health communications, not formal schooling. In particular, the link between variations in primary and upper-primary schooling and health belief was not vigorously pursued, perhaps because the developed world had already achieved universal primary education at the time of development of HBM. A small literature does emphasize the importance of individual and parental health belief in explaining better health outcome and behavior (but does not deal with the determinants of health belief as I do). The evidence is mixed here too. Miller (2011) shows how better maternal belief was correlated with better health outcome for their children in Kenya. Kan and Tsai (2004) find 6 a link between individuals’ belief concerning the health risks of obesity and their tendency to be obese in Taiwan. Contrarily, analyzing parents’ response to their children’s weight report card, Prina and Royer (2014) found no evidence that better parental belief leads to lowering of incidence of obesity. A subset of the research brings education, health belief and health behavior together such as Kenkel(1991) and and Hsieh et al. (1991) in the context of smoking in the US. However, the link is between knowledge and behavior with education being a mediating factor. 3 Sanitation and School Education Sanitation facilities (or lack thereof) have been getting attention among the highest policy circles in India. 5. This is both unsurprising and encouraging as the overall state of toilet facilities in India has remained poor despite the country achieving phenomenal economic growth since 1991. Unfortunately, obtaining reliable data both on general sanitation facilities and facilities in school is difficult. Official data has largely (and often deliberately) underestimated the lack of infrastructure, as evident from the discrepancies in numbers that emerge from various surveys 6 In my sample, I find general patterns that (i) toilets are missing from many schools, and (ii) not all schools with toilets have separate provisions for boys and girls. This is reported in Table 1. Please insert Table 1 Here We can see that the problem of lack of toilet is particularly severe in government schools where almost 40% of the schools do not have a toilet. Even when a school does have toilet facilities, it 5 Recently, in his address to the nation on India?s Independence Day, Prime Minister Mr. Narendra Modi has called for construction of toilets across schools of India as part of his “Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM)” ( Clean India) campaign. The government also promptly published a draft 6 Since the general lack of safe sanitation facilities in India is indisputable, I do not belabor on this point. Dean Spears maintains an excellent website on various sanitation issues in India http://riceinstitute.org/wordpress/author/dean-spears/. Interested readers are encouraged to consult it for further details. 7 may not necessarily have separate ones for boys and girls.7 The link between lack of sanitation and girl student drop out is a global phenomenon. According to UNICEF, one in ten school girls in Africa miss classes or drop out completely due to their period. Similar reports can be found in Asian countries like Bangladesh and Nepal. In India, both enrollment and completion rates for girl students have persistently been loIr than boys, particularly at the upper primary (6th to 8th grade) and secondary levels. For example, in 2002-2003, the year preceding the survey that I are using, 93% of the girls in the relevant age Ire enrolled in primary schools as opposed to 97% of the boys. [WDI, 2014]. However the wedge becomes 9% (65.3% for boys as opposed to 56.2% for girls) for the upper primary enrollments. 8 This means that girls drop out at a faster rate than boys. Though variables like parental gender preference, gender-biased employment market and cultural phenomena like early marriage may explain a part of the gap, it is increasingly understood that for young girls, menstruation creates an obstacle to schooling, leading girls to drop out of school once they reach puberty due to lack of adequate school based sanitation facilities and privacy. Empirically, there are conflicting claims on the effects of menstruation, lack of sanitary products, lack of toilets and girls? education. While Oster and Thornton (2011) do not find any effects of randomly distributing modern menstruation products to adolescent girls in Nepal, Adukia(2013) shows that inadequate school sanitation does hinders educational attainment in India. However, the results may be consistent as even though girls are equipped with sanitary products, lack of toilets, particularly separate toilets, in school may still prevent girls from attending school. Moreover, in many parts of Indian society, particularly in rural India, menstruation is often associated with taboos and ostracization. Since my identification strategy relies on girls achieving menarche and not either access to sanitary products or lack of toilets directly, it is consistent with multiple chan7 Since school information is provided in a different module in the survey, we cannot separate out rural and urban schools. 8 Note that one should use these numbers with caution. These are enrollment rates, while the actual attendance rates are likely to be much more less. 8 nels being at work simultaneously to make the probability of a girl dropping out of school at menarche higher. 4 Empirical Analysis In this section I use survey data from India to provide evidence on the impacts of education on health belief and belief. 4.1 Data and Sample Construction My data comes from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS), which is a nationally representative survey of 41,554 households located in 384 (out of 593 districts identified in 2001 Indian Census) districts in 33 states and union territories of India. The primary sampling unit is household(s) living in the same residence. The survey has a panel component, but since most of the variables of my interest are found only on the 2005 sample (and the panel component is much smaller), I restrict my analysis to cross-section data. It has two modules on individual and household data. The household module contains information on location including urban vs. rural location, family background such as religion and castes within religion and economic status. The second module was administered to 33,510 ever-married women aged 15-49. This module has detailed health and education related questions. IHDS is particularly suitable for my purposes, because not only does it ask very detailed demographic, economic and health questions, but it also contains some rare questions on health outcome, health belief, marriage practices and decision-making including the timing of menarche, age at first marriage, self-rated health and outcome of all pregnancies that it asks each ever-married woman. It also has both primary and constructed variables on religion and castes - categories that have historically played an immensely important role in Indian societies. These variables allow us to control for many competing hypotheses on the determinants of health belief. 9 To construct my sample, I first consider all ever-married women aged 15-49. Then I check for missing values and outliers. Having eliminated them, I are left with 33400 ever-married women in the relevant age range with roughly 64% living in rural areas. Table 2 reports mean and standard deviations of some key variables across rural and urban areas. For my identification strategy, I have included ever-married women who have at least one year of schooling. This is the only sample selection I have made. For girls who were never enrolled in school, as is the case for many children in India, dropping out of school is irrelevant. Therefore, my results need to be interpreted as the effects of additional schooling on health belief conditional on the student getting enrolled. 4.2 Selection of Variables IHDS contains a survey module called ‘Health Beliefs’ where all ever-married women ages 15-49 are asked about their opinion on a set of health-related questions such as - “Is it harmful to drink 1-2 glasses of milk every day during pregnancy?” or “Have you ever heard of an illness called AIDS?” my dependent variables come from this module where I have retained three questions on maternal health, neonatal health and AIDS. My independent variables belong to three categories: demographic, economic and locational, apart from my main variable of interest - number of years of schooling completed. 9 Among demographic variables, I control for age and age-squared. I control for both religion and caste of a woman. The survey categorizes five religions - Hindu (majority), Muslim, Christian, Sikh and Jain. There is a complex caste system among Hindus that is a vestige of thousands of years of social development. I follow the categorization in the survey. I use Brahmins as the base category as historically Brahmins have been the most privileged class in terms of social status and political power. There are other high castes like merchant class. Then there are numerous “lower” castes 9 Unfortunately, parental education is not available for most women. 10 categorized as “Scheduled Castes”, “Scheduled Tribes” and “Other Backward Classes”. “Dalits” constitutes the lowest rung of the caste hierarchy. Generally, these groups have historically suffered economic and social discrimination. Finally, there are tribal groups that often deviate from the mainstream socio-cultural-political architecture of Hindu casteism. 4.3 10 Descriptive Statistics Table 2 presents some relevant descriptive statistics. Though my subsequent analysis does not use all the variables, it is instructive to analyze these descriptive statistics to examine some national patterns to better understand my results. Columns (1), (2) and (3) show the means of the variables used in the study and some other relevant variables for the whole sample and by urbanity status respectively. I focus on urbanity because educational opportunities are very different in urban areas. I also see that for all the variables, average values in urban locations are significantly different from rural locations. The first variable reports the proportion of ever-married women aged 15-49 who report that their general health is “very good” as opposed to good and worse. Only less than 20% of the women interviewed deemed their health “very good” indicating a generally low level of self-rated health. 11 Rows 2-4 report averages for my three main dependent variables. Though statistically women residing in urban locations are different from those living in rural locations for all three variables, the difference is remarkable with respect to the variable that captures the answer to the question “Have you heard of a disease called AIDS?”. Overall, more than 40% of the respondents have reported to have not heard about AIDS. The proportion is more than 50% for rural women. This goes on to show that there is a large scope for enhancing health belief and awareness. There is also a big difference in the literacy rate between rural and urban location, attesting to the fact that rural India was still lacking in educational opportunities, at least at the time of the survey 10 An elaborate discussion of caste system is beyond the scope of this paper. self-rated health is not perfect as an indicator. However, the proportion is drastically loIr than, say, proportion of Americans who report self-rated health as “very good?. The comparable number for the U.S., according to the nationally representative National Health Interview Survey, is 62%. 11 Arguably, 11 in 2003. Please insert Table 2 Here 4.4 Econometric Modeling In this section I try to estimate the effects of additional schooling on health belief. I estimate regressions of the form Yi = b0 + b1 ⇤ Ei + Xi ⇤ b02 + ei , (1) where Yi is the dependent variable and represents one of the three health belief variables that I use - (i) belief of maternal health (ii) Neonatal health and (iii) AIDS awareness for the ith woman. It is a binary variable that takes value equals unity when the woman has the correct belief/awareness and zero otherwise. Ei represents years of schooling conditional on having enrolled in school, and Xi represents the following set of controls: age, age-squared, employment status (binary with employed equalling unity), urban location (binary with urban location equalling unity), indicator for individual belonging to below poverty line (binary with below poverty line equalling one) and religion and caste indicators with Hindu Brahmin being the base category. Finally, ei is the residual error term. Equation (1) can be estimated with a Probit model assuming normality of the error distribution. The estimated coefficient corresponding to the education variable would then show us the association between schooling and health belief. I will report this estimate as the baseline results for most of my estimations. However, for the reasons discussed in the introduction, Ei is likely to be endogenous, making my Probit estimate biased and inconsistent, and as a result, I cannot make causal interpretation of the role of education in health belief. my identifying assumption is that ages at menarche is largely exogenously determined and combined with the poor infrastructure in many schools in India, girls drop out after they reach 12 puberty. Consequently, girls having later puberty will have higher years of schooling on average. To capture this, I have created a variable called “late menarche” that assumes value of one if the respondent has reported her age at menarche to be 13 or higher, the global average and zero otherwise. 12 my instrumental variable strategy requires that age at menarche can explain variations in education even after controlling for other explanatory variables included in Xi above. Therefore, I estimate the following equation (2) along with equation (1) above, where Zi is a binary variable that takes value one is the reported age at menarche is 13 or higher and zero otherwise. Ei = a0 + a1 ⇤ Zi + Xi ⇤ a02 + ui , (2) Since all of my dependent variables are binary in nature (owing partly to the way the survey questions were designed) and my endogenous regressor is continuous, I estimate the system of equation (1) and (2) by the maximum likelihood method. Finally, robust standard errors are used in the analysis to correct for possible heteroscedasticity. I discuss alternative methods of estimating (1) and (2) and corresponding results in the robustness section. 4.5 Instrumental Validity An instrumental variable strategy has to pass a two-part validity test. First, it has to be relevant in the sense that the instrument should be able to explain variations in the endogenous variables even after controlling for all other explanatory variables. Second, it has to be exogenous and excluded in the sense that its effects on the dependent variable in equation (1) should transmit through the endogenous variable and not independently. I argue that women experiencing late menarche had higher schooling and age at menarche being biologically determined are orthogonal to the omitted variables that may affect education and health beliefs.13 12 I also perform the same analysis with a continuous measure of age at menarche. However, I a binary variable is less prone to recall error. 13 As far as my instrumental variable strategy is concerned, using age at menarche as an instrumental variable per se is not my innovation, though I am not aware of any work that used the variable for instrumenting education. The most 13 As the pattern in Figure 1 illustrates, the first requirement seems to be satisfied in the IHDS data. However, I need to control for the other explanatory variables to see if my instrument is relevant. 14 Table 3 reports the results from various first stage regressions. Column (1) does not include any controls and column (2) includes full set of controls. Column (3) includes district fixed effects allowing for the possibility that various district-level variables may drive educational outcomes of its residents. In all three specifications, the first stage is strong. The relevant variable, the indicator for late menarche, is positively and significantly associated with schooling. I also have very high values of F-stat assuaging any concern for weak instruments. Some notable aspects of the first stage results are the positive association between education and urbanity and negative association between education and poverty, as expected. Also, except for Christians, every other religious-caste group has loIr educational attainment than the base group Brahmins, who have historically been the most educated among all castes. Only counterintuitive result is the negative correlation between wage employment and education. The clue to this paradox can be found in the descriptive statistics table, where I can see that urban area has a higher wage labor force participation for the sample, which consists of ever married women. A large part of wage income comes from agricultural wage work that does not necessarily require formal schooling. Additionally, age at menarche has to be excluded from the main relationship between education health belief.instruments need to be orthogonal to the error term in the reduced form equation. Genetic factors are thought to be the strongest determinants of age at menarche. Research into the external determinants of age at menarche faces the same challenge of identifying the causal thorough use of this variable as an instrument has been made by Field and Ambrus (2008), though they instrument age at marriage with age at menarche. However, some of their other arguments are also relevant for my analysis, and I shall refer to them in section 4.5. In other studies, Rios-Neto and Miranda-Ribeiro (2009) use age at menarche as an instrument for sexual debut in Brazil. Mukhopadhyay and Crouse (2014) use age at menarche of a sibling as the instrument for BMI of a female respondent. Therefore, the particular strategy I use in this paper is novel. 14 To be sure, these results correspond to the estimation of (1) and (2) with or without controls for the first dependent variable “pregnancy belief”. As I will find out when I discuss my results, my estimation sample varies slightly depending on the outcome variable in use (due to non-reporting issues). Since the differences in the number of observations in are small, no qualitative difference can be found across these three specifications in terms of first stage regressions. I am reporting three columns instead of nine to avoid clutter. 14 effects of those variables. Since controlled field experiments are difficult to carry out in this field, some studies have either adopted ingenious methods in observational studies, while some have used laboratory experiments. In one remarkable study involving 1,283 pairs of monozygotic and dizygotic twins, Kaprio et al. (1995) found that the correlation between ages at menarche among monozygotic twins was three times more than their counterpart dizygotic twins confirming the importance of genetic factors. Laboratory experiments, however, show that a number of external factors such that extreme weather, physical stress, exposure to lead or plastic, peer-group sex composition and extreme changes in diets like malnutrition or obesity may delay or hasten puberty (Field and Ambrus, 2008). Among these, the last variable is of the most concern to us. 15 India, despite experiencing steady economic growth since 1991, still suffers from the problem of malnutrition. According to the UNISEF, one in three malnourished children in the world lives in India. There two reasons why this is not a big concern for our strategy. First, malnutrition is strongly correlated with poverty. There has not been any widespread and sustained food crisis or famine in India since 1955, the earliest year a 49 year old woman could have been born who was interviewed in 2004. Therefore, lack of access to food could only have been caused by lack of income. Second, in order to have any influence on the age at menarche biologically, malnutrition has to affect hormone-releasing agents. Laboratory experimental studies show that the form of malnutrition has to be extreme to precipitate a hormonal change that would alter the genetically determined age at menarche. 16 There is a well-established medical literature that argues that age at menarche is largely genetically determined. Though some recent studies like Dossus et al. (2012) find positive correlations between age at menarche and variables like income, urbanity and lifestyle, there is no conclusive evidence yet to defy the natural variations in the age of puberty. 15 India 17 is a tropical country with very few remote areas having extreme temperature. Very few adolescent girls perform hard labor. Lead and plastic pollutions are a concern only in urban settings and controlled for in our analysis. Finally, there is a priori reason to believe that some of these women had extraordinary peer group sex composition. 16 Discussion in paragraph has mostly been based on Field and Ambrus (2008) who perform a similar analysis in Bangladesh, a country that was formerly a part of India under British rule and share many characteristics like weather, economy and culture making such arguments relevant here also. 17 Field and Ambrus (2008) offer a comprehensive discussion of the role of genetic factors in the determination of 15 Please insert Table 3 Here My main concern is whether age at menarche directly affects health belief. One can reasonably argue that girls having early maturation may also start learning about reproductive health sooner. Hence they are more likely to report higher incidence of correct belief. If this is the case, then I would see a positive association between health belief and early onset of menarche (which would translate into a negative association between health belief and the variable I are using in this paper - late menarche). This is not the case as Table 4 shows. Late onset of menarche is associated positively and significantly with health belief suggesting that there is no prima facie evidence of early menarche directly leading to better health belief. Please insert Table 4 Here 5 Main Results The section presents empirical results on the impact of schooling on health belief. The results for estimating equation (1), and the system of equations (1) and (2) are reported in Tables 5A5C, when the dependent variables are pregnancy health belief, neonatal health belief and AIDS awareness respectively. There are four columns in each of them. Columns (1) and (3) provide single equation Probit model estimates (marginal effects) from equations of form (1). Columns (2) and (4) report results from joint estimation of (1) and (2) by maximum likelihood methods. The columns are also organized to separate estimates without controls (columns (1) and (2)) from with controls (columns (3) and (4)). age at menarche including references that date before 2008. They also explain how some of the laboratory findings in developed country are not relevant for country like Bangladesh. Since they belong to the subcontinent (and indeed part of the same nation for many years) such arguments are valid in this case also. I do not repeat those arguments here. 16 I start with the estimates from single equation Probit models as they provide the baseline indication of possible correlation between the dependent and the main explanatory variable. Without any controls and correction for endogeneity, there is a statistically significant positive effect of education on health belief for all three dependent variables as columns (1) and rows (1) show in tables 3A-3C. The results indicate that an additional year of schooling by itself can lead to an increase in the probability of having relevant health belief by .02 percent point to 4 percent points. However, when I introduce controls, the average return to one extra year of education is not significant for pregnancy health belief according to Probit estimates. Though for the other two dependent variables schooling remains positive and significant even after introducing controls. Please insert Table 5A-5C Here Looking at columns (2) and (4), my instrumental variable estimates suggest a strong and positive effect of schooling on health beliefs. The effects are substantial: even after controlling for several variables, an extra year of schooling for an average woman is likely to increase correct health belief by 22%. That estimators that do not correct for endogeneity underestimate the effects of educational attainment is shown elsewhere in the literature (Card, 1999, 2001; Griliches, 1977). Though my dependent variables are unconventional (not income or wages), similar logic can explain the potential underestimated values of Probit estimates. If motivation and/or intelligence enhance health belief, as is intuitive, and if they are omitted from the regression, they are likely to bias the Probit estimates downward. Similar effects are obtained for the other two dependent variables under consideration. In both of these cases, educational attainment is positive and significant without controlling for endogeneity, but instrumental variable estimates are larger in magnitude. Interestingly, the results suggest that it is not generally the case that rural and poor women have worse health beliefs for the first two variables that deal with reproductive health. However, as far as AIDS awareness is concerned, the effects are reversed. The conclusion from this section is that while educational attainment matters, the exact nature of such influence in interaction with other 17 variables is not homogenous. Depending on the nature of the question concerned, I get divergent patterns. I will elaborate on this point in section 7. 6 Robustness In this section I perform two sensitivity analyses to check if my results are robust to alternative specification and estimation methods. First, instead of my baseline maximum likelihood estimation, I use linear two-stage estimation. While the former guarantees that the predicted values of the (binary) dependent variable will lie between zero and one, it depends on the assumption of joint normality of error terms. This may be a tenuous assumption in practice. An alternative is to estimate the model using linear 2SLS method. According to Angrist (1991), there exist conditions under which linear instrumental variables will consistently estimate average treatment effects. Results from linear 2SLS are presented in Panel A of Table 6. Comparing the coefficient estimate for the dependent variable pregnancy health belief with my baseline estimate (Table 5A, row (1), Column (4)), I are assured that not only are the estimates qualitatively same, they are also quantitatively similar. Similar patterns can be found for the other two dependent variables also. Please insert Table 6 Here Second, I include district fixed effects in my estimates. Districts are possibly the most important administrative units in India. There are 630 districts belonging to 27 states. Districts vary widely in terms of infrastructure like road and schools even within a state. Therefore, there may be observed and unobserved variables at the district level that may drive the educational achievements of its residents. Inclusion of district fixed effects imposes greater burden on other explanatory variables as my outcome variables can potentially be explained mostly by location. However, as Panel B of Table 4 shows, the effects of education remains significant, though the magnitude is diminished after controlling for the district fixed effects. 18 7 Caveats - Schooling does not improve all health belief The health belief questions that I analyzed so far are rather personal in nature for ever-married women of 15-49 years. The same survey module also contains questions that are not related to reproductive or sexual health. It asks (i) question on indoor air pollution (Is smoke from a wood/dung burning traditional oven good for health, harmful for health or do you think it doesn’t really matter?); and (ii) question on male sterilization (Do men become physically weak even months after sterilization?). This section examines if higher educational attainment leads to better awareness on these issues. The brief answer is the negative. Please insert Table 7 Here The results are presented in Table 7. For brevity I have presented only the maximum likelihood IV estimates, my baseline model. The first row shows that in the case of indoor pollution, schooling has no significant on an individual woman’s belief on indoor pollution caused by the smoke from a wood or dung-burning oven. For the second variable, educational attainment actually has a negative and significant effect on correct belief. Interestingly, for the other control variables, the pattern of significance is as expected - urban women know better, women living below poverty line know worse (though not significantly in one case) and every other caste-religious group (except Christians) know worse than Brahmins, the historically learned caste. The health effects of indoor pollution in developing countries has received attention from social scientists only recently (Balakrisnan et al., 2013; Gall et al., 2013; Hanna, 2014). Though the ill-effects of using indoor ovens is well-documented, the reason as to why a large section of world population is using such technology is not clear. The latest explanation comes from Kishore (2013), who argues that in India, women’s position in the household is a determinant of the use of traditional oven. My analysis provides a simple explanation - despite the international spread in awareness, a large section of the poor in the world are still in the dark on the negative effects 19 of indoor air pollution. Unfortunately, the results suggest that formal schooling does not play any role in promoting such awareness also. This is not unexpected, as environmental issues were not included in school curriculum in India before 2005, the year of the survey. The results for male sterilization question is not surprising. Though male sterilization as a family planning to tool has been available in India for some time, the awareness level has always been low. In fact in a recent study Mahapatra et al. (2014) has found that awareness on modern methods of male sterilization is lacking even among community workers interviewed. Sex education in Indian school is in its infancy and topics of intercourse and reproduction remain largely taboo in Indian schools, both urban and rural. Therefore, the results that formal schooling does not enhance knowledge on contraceptive behavior of opposite sex should not come as a surprise. 8 Conclusion and Policy Implications In this paper I have explored the role schooling attainment plays in forming correct health beliefs among ever-married women between ages 15-49 in India and find that for these women, higher schooling significantly leads to better health belief with respect to reproductive health and AIDS awareness. On the contrary, schooling does not seem to play a role in enhancing belief on indoor pollution or men’s health. To correct for the potential endogeneity introduced by the schooling variable, I have used age at menarche as an instrument for schooling noting that in India many girls leave school after they reach puberty due to poor sanitary conditions in their schools. I find that age at menarche is a strong predictor of schooling achievement with girls having late menarche going on to have more years of schooling. Combined with the biological evidence that forces that are exogenous to my structural relationship determine age at menarche, I argue that I have been able to establish a causal relationship between education and health belief. This is the main contribution of the paper. This relationship is at the confluence of education and health policy. Poor countries often 20 struggle to spread awareness on diseases like AIDS. my results suggest that expansion in schooling, particularly in rural areas, through better infrastructure can go a long way in aiding such efforts. Improvements in sanitation can go a long way to combating the problem. In particular, building toilets in schools enables girls to manage their periods more easily. Fortunately, expansion of sanitation has been a priority in Indian public policy over the past few years. Hopefully, education and health outcomes would improver in the near future. 21 References Adukia, A. (2013). Sanitation and Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Education. Alsan, M. M., & Cutler, D. M. (2013). Girls’ education and HIV risk: Evidence from Uganda. Journal of Health Economics, 32(5), 863-872. Angrist, J. (1991). Instrumental variables estimation of average treatment effects in econometrics and epidemiology. NBER Working Paper. Balakrishnan, K., Ramaswamy, P., Sambandam, S., Thangavel, G., Ghosh, S., Johnson, P., & Thanasekaraan, V. (2011). Air pollution from household solid fuel combustion in India: an overview of exposure and health related information to inform health research priorities. Global health action, 4. Berger, M. C., & Leigh, J. P. (1989). Schooling, self-selection, and health. Journal of Human Resources, , 433-455. Braakmann, N. (2011). The causal relationship between education, health and health related behaviour: Evidence from a natural experiment in England. Journal of Health Economics, 30(4), 753-763. Card, D. (2001). Estimating the return to schooling: progress on some persistent econometric problems, Econometrica, 69(5): 1127-1160. Card, D. (1999). The Causal Effect of Education on Earnings, in (O. Ashenfelter and D. Card, eds). , Handbook of Labour Economics, vol. 3A. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, North-Holland, and pp.-1801– 1863. Carpenter, C. J. (2010). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health communication, 25(8), 661-669. Cutler, D. M., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2010). Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics, 29(1), 1-28. Dossus, L., Kvaskoff, M., Bijon, A., Fervers, B., Boutron-Ruault, M. C., Mesrine, S., & Clavel-Chapelon, F. (2012). Determinants of age at menarche and time to menstrual cycle regularity in the French E3N cohort. Annals of epidemiology, 22(10), 723-730. Field, E., & Ambrus, A. (2008). Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in Bangladesh. Journal of Political Economy, 116(5), 881-930. 22 Griliches, Z. (1977). Estimating the Returns to Schooling: Some Econometric Problems, Econometrica, 45: 1-22. Gall, E. T., Carter, E. M., Matt Earnest, C., & Stephens, B. (2013). Indoor air pollution in developing countries: research and implementation needs for improvements in global public health. American journal of public health, 103(4), e67-e72. Greenstone, M., & Hanna, R. (2011). Environmental regulations, air and water pollution, and infant mortality in India. American Economic Review, October. Hsieh, C., Yen, L., Liu, J., & Chyongchiou Jeng Lin. (1996). Smoking, health knowledge, and anti-smoking campaigns: An empirical study in Taiwan. Journal of Health Economics, 15(1), 87-104. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-6296(95)00033-X Jürges, H., Reinhold, S., & Salm, M. (2011). Does schooling affect health behavior? Evidence from the educational expansion in Western Germany. Economics of Education Review, 30(5), 862-872. Kan, K., & Tsai, W. (2004). Obesity and risk knowledge. Journal of Health Economics, 23(5), 907-934. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.12.006 Kenkel, D. S. (1991). Health behavior, health knowledge, and schooling. Journal of Political Economy, , 287-305. Kishore, Avinash. "Essays on Economics of Indoor and Outdoor Air Pollution in India." Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn3:HUL.InstRepos:10403669 Lavy, V., & Zablotsky, A. (2011). Mother's schooling, fertility, and children's education: Evidence from a natural experiment. National Bureau of Economic Research. MAHAPATRA, Swati et al. Assessment of knowledge and perception regarding male sterilization (Non-Scalpel Vasectomy) among community health workers in Jharkhand, India. Indian Journal of Community Health, [S.l.], v. 26, n. 4, p. 428433, dec. 2014. ISSN 2248-9509. Miller, E. M. (2011). Maternal health and knowledge and infant health outcomes in the Arial people of northern Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 73(8), 1266-1274. Mukhopadhyay, S. (2014). Causal effects of BMI on wage. Mimeo. Department of Economics, University of Nevada Reno. 23 Oster, E., & Thornton, R. (2011). Menstruation, sanitary products, and school attendance: Evidence from a randomized evaluation. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 91-100. Prina, S., & Royer, H. (2014). The importance of parental knowledge: Evidence from weight report cards in Mexico. Journal of Health Economics, 37(0), 232-247. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.07.001 Rios-Neto and Miranda-Ribeiro (2009) : Intra- and intergenerational consequences of teenage childbearing in two Brazilian cities: Exploring the role of age at menarche and sexual debut. Paper presented at the XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference, Marrakech, Sep 27- Oct 2, 2009. Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education & Behavior, 2(4), 328-335. Spears, D. (2012). Effects of rural sanitation on infant mortality and human capital: evidence from India's Total Sanitation Campaign. Mimeo. Princeton University. WDI (World Development Indicator) Database (2014). World Bank. Washington, DC. 24 Figure 1. Relationship between age at menarche and average schooling. 25 Table&1:&&School&Toilet&Facilities&in&the&Sample& & (1) Variable School has a toilet (binary; =1 if yes) Observations Standard deviations in brackets Variable School has separate toilets (binary; =1 if yes), conditional on school having a toilet and admitting girls Observations Standard deviations in brackets 26 Government Schools 0.6092 (.4881) 2031 (2) Private Schools 0.7832 (.4122) 1748 Government Schools Private Schools 0.7532 (.4313) 1236 0.7928 (.4054) 1369 Table&2.&Descriptive&Statistics& ! Variable Self-rated health very good Correct belief Pregnancy Correct belief breast serum Aware of AIDS Literate Dummy Years of Schooling Employed Married within same caste Arranged Marriage Gold Dowry Common Cash Dowry Common No access to electricity Observations Standard deviations in brackets *** Significant at the 1% level (1) Total (2) Rural (3) Urban 0.1556 (.3625) 0.7785 (.4153) 0.7562 (.4294) 0.5877 (.4922) 0.5596 (.4964) 4.6257 (4.8087) 0.2345 (.4237) 0.945 (.228) 0.572 (.4948) 0.7513 (.4323) 0.3991 (.4897) 0.2122 (.4089) 33400 0.1386 (.3455) 0.7663 (.4232) 0.7367 (.4404) 0.4723 (.4992) 0.4616 (.4985) 3.3968 (4.1905) 0.2895 (.4535) 0.9515 (.2147) 0.5811 (.4934) 0.7106 (.4535) 0.414 (.4926) 0.3026 (.4594) 21398 0.1861 (.3892)*** 0.7997 (.4003) *** 0.791 (.4066) *** 0.7925 (.4055) *** 0.7342 (.4418) *** 6.8053 (5.056) *** 0.1365 (.3433) *** 0.9333 (.2495) *** 0.5559 (.4969) *** 0.8239 (.381) *** 0.3725 (.4835) *** 0.0518 (.2216) *** 12002 Notes: For all variables the p-value for the t-test between urban and rural is less than 0.01 making the difference significant at 1% level. The values are not reported to avoid clutter. 27 Table 3: First Stage Results Dependent Variable - Years of Schooling Late_menarche (1) 0.53 (0.051) Age Age-squared Employed URBAN POOR (2) 0.418*** (0.0480) 0.121*** (0.0228) -0.00264*** (0.000347) -0.205*** (0.0731) 1.904*** (0.0484) -1.575*** (0.0650) (3) 0.415*** (0.0488) 0.115*** (0.0228) -0.00257*** (0.000346) -0.169** (0.0739) 1.955*** (0.0504) -1.564*** (0.0661) -0.676*** (0.100) -1.398*** (0.0959) -2.170*** (0.105) -1.663*** (0.145) -2.265*** (0.116) -0.425** (0.174) 0.818*** (0.172) YES Caste/Religion Groups: (Base Group is Brahmin) Other High caste District FE p-value for Fstatistic NO -0.610*** (0.0984) -1.377*** (0.0941) -2.098*** (0.103) -1.461*** (0.139) -2.170*** (0.114) -0.370** (0.173) 0.933*** (0.172) NO 0.00 0.00 0.00 Observations 18,010 18,010 17,851 OBC Dalit Adivasi Muslim Sikh, Jain Christian Notes: Robust Standard Errors are in parentheses *** Significant at the 1% level, ** Significant at the 5% level, * Significant at the 10% level The sample size refers to the second stage regressions with the dependent variable “Correct belief on Pregnancy Health Question” Please refer to the Appendix for detailed variable descriptions. 28 Table 4: Correlation between late menarche and health belief late_menarche N (1) (2) (3) Pregnancy Health Neo-natal Health Question AIDS Awareness 0.136*** (0.0158) 31677 0.183*** (0.0151) 33006 0.0991*** (0.0140) 33144 Notes: Robust Standard Errors are in parentheses. *** Significant at the 1% level, ** Significant at the 5% level, * Significant at the 10% level Please refer to the Appendix for detailed variable descriptions. 29 Table 5A: Probit and Instrumental Variable Estimates of the Effects of Education on Health Belief Dependent Variable: Correct belief on Pregnancy Health Question (1) Probit (2) IV (3) Probit (4) IV 0.00258*** (0.000880) 0.192*** (0.0207) 0.000593 (0.000973) 0.000108 (0.00310) 7.21e-06 (4.67e-05) 0.0201** (0.00877) 0.0350*** (0.00647) 0.00374 (0.00933) 0.220*** (0.0239) -0.0263*** (0.00979) 0.000599*** (0.000154) 0.0977*** (0.0274) -0.325*** (0.0566) 0.355*** (0.0463) -0.0127 (0.0120) -0.0159 (0.0116) -0.0142 (0.0131) -0.0321* (0.0179) -0.0768*** (0.0150) 0.0130 (0.0211) 0.0354* (0.0196) 18,010 0.104** (0.0422) 0.272*** (0.0531) 0.432*** (0.0688) 0.254*** (0.0703) 0.306*** (0.0849) 0.106 (0.0697) -0.0819 (0.0727) 18,010 VARIABLES Years of Schooling Age Age-squared Employed URBAN POOR Caste/Religion Groups: (Base Group is Brahmin) Other High caste OBC Dalit Adivasi Muslim Sikh, Jain Christian Observations 18,029 18,029 Notes: Robust Standard Errors are in parentheses *** Significant at the 1% level, ** Significant at the 5% level, * Significant at the 10% level Coefficients are marginal effects. Please refer to the Appendix for detailed variable descriptions. 30 Table 5B: Probit and Instrumental Variable Estimates of the Effects of Education on Health Belief Dependent Variable: Correct belief on Neo-natal Health Question VARIABLES Years of Schooling (1) Probit (2) IV (3) Probit (4) IV 0.0148*** (0.000846) 0.274*** (0.00605) 0.0145*** (0.000923) 0.00248 (0.00291) -2.80e-06 (4.40e-05) 0.0199** (0.00834) -0.00377 (0.00609) 0.0397*** (0.00878) 0.306*** (0.00619) -0.0291*** (0.00837) 0.000731*** (0.000127) 0.0934*** (0.0255) -0.536*** (0.0233) 0.513*** (0.0251) -0.0269** (0.0117) -0.0126 (0.0111) -0.0243* (0.0125) -0.136*** (0.0183) -0.0603*** (0.0139) 0.0769*** (0.0174) 0.112*** (0.0151) 18,476 0.130*** (0.0369) 0.385*** (0.0373) 0.557*** (0.0441) 0.227*** (0.0603) 0.534*** (0.0502) 0.263*** (0.0689) 0.0806 (0.0788) 18,476 Age Age-squared Employed URBAN POOR Caste/Religion Groups: (Base Group is Brahmins) Other High caste OBC Dalit Adivasi Muslim Sikh, Jain Christian Observations 18,495 18,495 Notes: Robust Standard Errors are in parentheses *** Significant at the 1% level, ** Significant at the 5% level, * Significant at the 10% level Please refer to the Appendix for detailed variable descriptions. 31 Table 5C: Probit and Instrumental Variable Estimates of the Effects of Education on Health Belief Dependent Variable: Correct belief on AIDS Awareness (1) Probit (2) IV (3) Probit (4) IV 0.0460*** (0.000827) 0.295*** (0.0222) 0.0398*** (0.000903) 0.00985*** (0.00260) -0.000138*** (3.95e-05) 0.00194 (0.00732) 0.114*** (0.00560) -0.0303*** (0.00739) 0.299*** (0.0293) 0.0215 (0.0133) -0.000169 (0.000221) 0.0357 (0.0319) 0.187* (0.110) 0.102 (0.0782) 0.0102 (0.0118) -0.0142 (0.0113) -0.0130 (0.0123) -0.0547*** (0.0158) -0.0884*** (0.0138) -0.0143 (0.0208) 0.119*** (0.0163) 18,539 0.134** (0.0562) 0.150* (0.0797) 0.256** (0.105) 0.0208 (0.101) 0.00189 (0.128) -0.0138 (0.0870) 0.562*** (0.139) 18,539 VARIABLES Years of Schooling Age Age-squared Employed URBAN POOR Caste/Religion Groups: (Base Group is Brahmins) Other High caste OBC Dalit Adivasi Muslim Sikh, Jain Christian Observations 18,557 18,557 Notes: Robust Standard Errors are in parentheses *** Significant at the 1% level, ** Significant at the 5% level, * Significant at the 10% level Please refer to the Appendix for detailed variable descriptions. 32 Table 6: Robustness Tests PANEL A: 2SLS Estimates (1) VARIABLES Pregnancy (2) Neonatal Years of Schooling 0.229*** 0.306*** (0.0233) (0.00700) Observations 17,851 18,456 Standard errors in brackets *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 (3) AIDS 0.325*** (0.0229) 18,539 PANEL B: Estimates including District Fixed Effects (1) (2) (3) VARIABLES Pregnancy Neonatal AIDS Years of Schooling 0.0943*** 0.214*** (0.0179) (0.0236) Observations 17,525 17,981 Robust standard errors in brackets *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 0.0872*** (0.0128) 18,042 Notes: Both regressions control for all the variables included in Tables 3A-3C. 33 Table 7: Effects of Education on Alternative health belief questions VARIABLES Years of Schooling Age Age-squared Employed URBAN POOR Sterilization Indoor Pollution -0.234*** (0.0198) 0.0427*** (0.00943) -0.000814*** (0.000145) -0.0253 (0.0285) 0.588*** (0.0253) -0.425*** (0.0355) -0.0151 (0.0493) 0.0127 (0.0125) -0.000191 (0.000211) -0.0958*** (0.0317) 0.183** (0.0925) -0.123 (0.0828) -0.149*** (0.0392) -0.352*** (0.0450) -0.572*** (0.0517) -0.201*** (0.0678) -0.597*** (0.0554) -0.214*** (0.0680) 0.674*** (0.0844) 13,760 -0.261*** (0.0552) -0.348*** (0.0794) -0.209* (0.114) -0.511*** (0.0896) -0.484*** (0.114) 0.170* (0.102) 0.0419 (0.0970) 18,535 Caste/Religion Groups: (Base Group is Brahmins) Other High caste OBC Dalit Adivasi Muslim Sikh, Jain Christian Observations Standard errors in brackets *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 Please refer to the Appendix for detailed variable descriptions. 34 Appendix Dependent Variables: Correct belief on Pregnancy Health Question: Survey Question: Is it harmful to drink 1-2 glasses of milk every day during pregnancy? Correct belief on Neo-natal Health Question: Survey Question: Do you think that the first thin milk that comes out Good=1 after a baby is born is good for the baby, harmful for the baby, or it doesn't matter? Correct belief on AIDS Awareness Survey Question: Have you ever heard of an illness called AIDS? Sterilization Survey Question: Do men become physically weak even months after sterilization? Indoor Pollution Survey Question: Is smoke from a wood/dung burning traditional chulha good for health, harmful for health or do you think it doesn't really matter? Instrumental Variables: Late_menarche: = 1 if age at menarche >12, 0 otherwise. Explanatory Variables: Age, Age-squared: Continuous varables. Employed = 1 if wage-employed, 0 otherwise URBAN = 1 if urban location, 0 otherwise POOR = 1 if below poverty line, 0 otherwise 35