Research Brief

Research Brief

DCSF-RB019

January 2008

ISBN 978 1 84775 085 3

WHAT MAKES A SUCCESSFUL TRANSITION FROM PRIMARY TO

SECONDARY SCHOOL?

Findings from the Effective Pre-school, Primary and Secondary

Education 3-14 (EPPSE) project

Maria Evangelou

1

, Brenda Taggart

2

, Kathy Sylva

1

, Edward Melhuish

3

, Pam Sammons

Iram Siraj-Blatchford

2

4 and

Introduction and Background

The transition from primary to secondary school is important in the lives of children and their families, yet research has shown that transitions can be stressful for children, that continuity of curriculum between primary and secondary school may suffer during transition and that some vulnerable children need intervention prior to transition (McGee et. al., 2004). In addition, the progress pupils make at primary school may not always be maintained after the move to secondary level. The Government’s

Five Year Strategy for Children and Learners has acknowledged that “ too many children still find the transition from primary to secondary school difficult –some fall back in their learning as a result” (DfES,

2004, p.61

).

As part of its commitment to ensuring that every young person achieves their full potential, the Government's Strategy aims to provide all pupils with a smooth transition from primary to secondary school.

This report presents the findings of a sub-study on transitions undertaken as part of the Effective Preschool, Primary and Secondary Education 3-14 (EPPSE 3-14 project), a major longitudinal study investigating the influence of pre-school, primary and secondary school on children’s cognitive and social/behavioural development in England. The transitions sub-study of more than 500 children and families sheds light on current transition practices and highlights what helps and hinders a successful transition. It takes into account the influence of child and family background characteristics such as socio-economic status (SES) and gender. It suggests how the transition experience could be improved to enhance smooth continuity between primary and secondary school.

Key findings

•

A range of practices were employed by schools which helped to support children's transitions including: the use of ‘bridging materials’; the sharing of information between schools; visits to schools by prospective teachers, children and their parents; distribution of booklets; talks at the schools; taster days and other joint social events between schools.

•

Most children (84%) said they felt prepared on entry to secondary school. Many believed that their family and/or teachers helped them to prepare by addressing worries, reassuring and encouraging them, explaining what to expect and how secondary school works, and by giving advice and tips on how to cope at their new school. A noteworthy minority, (16%), did not feel prepared when they changed schools, but only 3 per cent of children were worried or nervous a term after starting their secondary school .

1

Department of Education, University of Oxford,

2

Institute of Education, University of London, of Children, Families and Social Issues, Birkbeck University of London,

4

3

Institute for the Study

School of Education, University of

Nottingham

•

The data analysis revealed five aspects of a successful transition. A successful transition for children involved: o o o o o developing new friendships and improving their self esteem and confidence, having settled so well in school life that they caused no concerns to their parents, showing an increasing interest in school and school work, getting used to their new routines and school organisation with great ease, experiencing curriculum continuity.

•

Children who felt they had a lot of help from their secondary school to settle in were more likely to have a successful transition. This included help with getting to know their way around the school, relaxing rules in the early weeks, procedures to help pupils adapt, visits to schools, induction and taster days, and booklets.

•

If children had experienced bullying at secondary school, had encountered problems with dealing with different teachers and subjects or making new friends, then they also tended to experience a negative transition.

•

Low SES (socio-economic status) has been found to have an association with less positive transitions for children.

Aims

The aims of the project were:

•

•

•

To explore transition practices and identify successes and challenges in the six Local Authorities who were part of the original EPPSE study,

( www.ioe.ac.uk/projects/eppe ).

To explore the processes that support a pupils’ transition from primary to secondary schools and to identify any hindrances to a successful transition.

To explore the experiences and perceptions of both pupils and their parents of the transition process.

•

•

To identify any background characteristics of pupils and families that are associated with more positive transitions.

To describe the specific practices that lead to positive and negative transitions

(as reported by pupils and parents).

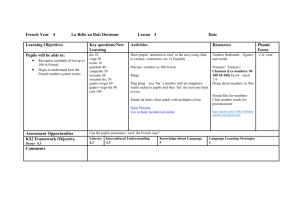

Methodology

By adopting a mixed methods approach, the study investigated the issues relating to transition for four distinctive groups: Local

Authorities (LA), children, parents and schools.

Officers in six Local Authorities were asked about the way transition was dealt with in their

Authority. Children at the end of their first term at secondary school completed a questionnaire on their thoughts and experiences of transition, and the study also sought their parents’ opinions in order to illustrate the whole family’s experience.

Finally, there were twelve case studies selected from the respondents of the questionnaire because of their positive experiences of transition. These involved interviews with the children and their primary and secondary teachers. This provided further details of the systems in place that support the transition processes between school phases.

The sample was drawn from 1190 children and their parents in the wider EPPSE project, who were making the transition to secondary school at the end of the 2005-06 academic year.

Responses were received from 550 children (a

46% response rate) and 569 parents from across England. The sample was selected from

6 Local Authorities in five regions (a Shire

County, an Inner London borough, a

Metropolitan authority in the Midlands, an East

Anglian authority, and two authorities in the

North East), being representative of urban, rural and inner-city areas (Sammons, Sylva et al.,

1999). Children were recruited to the case studies using stratified selection to get a balanced mix by region, gender, socioeconomic status (SES) and ethnicity. A wide range of data, already available from the main

EPPSE study was used to complement the analyses.

Current transition practices

The Local Authorities were responsible for the secondary admissions procedure, and issued information on this to schools and parents. The primary schools shared information on Key

Stage 2 results, attendance and special educational needs of individual pupils with the secondary schools. The interviews with the six

LA officials revealed that secondary schools do not appear to ‘trust’ the data on children provided by primary schools at Year 6 level, and this leads to a system of baseline re-testing of all children at Year 7. Guidelines on good practice, opportunities for training and formal systems to evaluate training and practice differed enormously between the six Local

Authority areas. Choice Advisors, a new

Government initiative being delivered in some areas, provide impartial advice and support to parents.

There were some interesting initiatives to ensure that children and their parents knew about secondary schools and felt comfortable with the process of transfer. These included information booklets about the secondary schools, open days, talks by the secondary teachers, and meetings with other children and staff. Visits to secondary schools were for whole classes at primary school or for families, where they could see examples of work and sample lessons. There were also visits by Year

7 teachers to feeder primary schools to help familiarise children with the teachers they would meet. Some schools structured the first day of

Year 7 so that the children were the only pupils at the school and could experience the space and facilities without other pupils around.

To help curriculum continuity some schools used ‘bridging materials’ where the same work books were used in both Years 6 and 7. There was some sharing of information on the skills and understanding pupils had achieved and on the style of lessons, for example, through the visit of Year 7 teachers to Year 6 classrooms to watch the class work and talk to individual pupils. Secondary school teachers initiated most of the contact.

In the schools attended by children in the study, there were various strategies used to support children in their transition to secondary school.

Most children (82%) attended open days.

These included tours of the school, head teacher talks, and meetings with other teachers and children. The majority of children said that their primary school teacher had talked to them about having more than one teacher in Year 7, behaviour and discipline, and changing classrooms between lessons. Half of the children had also been informed about having new subjects, and not being with the same pupils in all lessons. In many cases (63%), a

Year 7 teacher would have also visited the primary school during which they would have talked to the class/small group (68%), watched the class working (18%), taught the class

(17%), talked to individual pupils (13%) and/or talked during assembly (12%). Most children

(81%) had also paid additional visits to their new secondary school. Many children had also visited their new secondary school for special lessons, evening meetings for parents and children and attended joint events. Only seventeen per cent of the parents mentioned that their child had been assigned an older pupil as a mentor in secondary school.

Key Features of a Successful Transition

According to LA officers, a successful transition was one where the process was managed smoothly – with parental choices received on time, most parents getting their first choice of school and few appeals.

The analysis of the survey responses of children and their parents was used to identify children who had experienced a successful transition, defined in terms of the following five factors: children had greatly expanded their friendships and boosted their self-esteem and confidence once at secondary school; they had settled so well in school life that they caused no concerns to their parents; they were showing more interest in school and work in comparison to primary school; they were finding it very easy getting used to new routines; and/or they were finding work completed in Year 6 to be very useful for the work they were doing in Year 7.

One of the main features affecting a successful transition included whether or not children had received a lot of help from their secondary school. The sort of help that secondary schools could provide to their new pupils included: help with getting to know their way around the school, relaxing rules in the early weeks, procedures to help pupils adapt, visits to schools, induction and taster days, and

booklets, offering adequate information, encouragement, support and assistance with lessons and homework. The vast majority of children had been taught by their secondary schools how to use reference sources (90%), how to revise (87%), how to make notes (80%), and how to write an essay (77%). The majority of parents (80%) reported they had received enough feedback from the school about their child's progress and behaviour.

Other things that promoted a positive transition among children included: looking forward to going to secondary school; the friendliness of the older children at secondary school and those in their class; having moved to the same secondary school with most of their primary school friends; having older siblings who could offer them advice and support; and finding their new school work interesting.

Eighty four per cent of children had felt prepared for moving to secondary school, and after spending a term at their new school, nearly three quarters of the children said they felt happy. However, there were children – albeit a minority – who did not feel prepared.

What hinders a successful transition?

Local Authority officers felt that parents not understanding the admissions process, or trying to ‘subvert’ the system (e.g. pretending to live in an area to get a better chance of a school place) caused problems. In urban areas, problems may also have arisen where neighbouring authorities had different procedures – which often caused confusion among parents. There was also some concern about the National Pupil Database, which some

LA officers reported as not being sufficiently upto-date and occasionally holding duplicate records.

For children, analysis of the survey showed that experiences of bullying, worrying about their ability to do the work or about having new and different teachers for subjects, or worrying about whether they can make friends, were all associated with a poor experience of transition.

It is worth mentioning, that approximately 3 in every 10 children had some or many experiences of bullying according to their parents. Of the 165 parents who reported that their children had experienced some or a lot of problems with bullying 63 per cent of these children did not expand their friendships and did not boost their self-esteem and confidence;

72 per cent of these children did not settle well and were of particular concern to their parents; and 66 per cent of children did not get used to the new routines with great ease.

Transitions for vulnerable children

Overall, children with special educational needs

(SEN) or those from other vulnerable groups did not experience a less successful transition than other children. However, the survey data did highlight some interesting findings. Children with SEN, approximately 20 per cent of children in the sample, were more likely to be bullied – which is a key inhibitor of a successful transition. Out of the 110 children with SEN in the sample, 37 per cent had problems with bullying compared with 25 per cent of children without SEN who had problems with bullying.

On the positive side, children with SEN and other health problems were experiencing greater curriculum continuity between Years 6 and 7. It may be that the earlier and more individual transfer process that these children experience has prepared them better for the move and the work they will do in Year 7.

Of the 102 children living in low SES households, 72 per cent did not get used to the new routines with great ease and 58 per cent did not settle in very well. In comparison, of the

186 high SES children, 50 per cent did not get used to the new routines with great ease and

39 per cent did not settle in so well that they would cause no concern to their parents.

However, children of low SES did look forward to secondary school, which had a positive effect on them developing an interest in school and school work.

Conclusions and implications

This study was commissioned in light of concern about the transition experiences of children moving from primary to secondary school. Most of the children in the study had a positive transition experience, but a noticeable minority did not.

For children, parents and schools, the factors that identify a successful transition can be summarised as; social adjustment, institutional adjustment and curriculum interest and continuity. This report highlights a number of

influences that shape children’s transfer experiences and the likelihood of a successful transfer.

Social adjustment

The research identified that one important indicator of a successful transition was the extent that children have more and new friendships and higher self-esteem and report greater confidence after their transition to secondary school. The research suggests there is a need to help children develop their social and personal skills (friendships, self-esteem and confidence). Secondary schools could involve older children to help Year 7 children settle and this strategy may alleviate children’s and parents’ worries as well as reduce incidents of bullying. It is appropriate to develop clear systems to identify bullying and offer guidelines for Year 7 tutors, in order to refer those who appear to have problems after transfer to a support system or a scheme of

“buddies”. Older children in the school could assume the role of “an older sister/brother” since children with older siblings adjusted better in this regard. Using the PSHE (Personal,

Social and Health Education) curriculum to develop these skills, as well as using the period after the KS2 national assessments as a key period to help prepare children could help both in the transition process as well as the PHSE skills of older pupils.

Institutional adjustment

The survey showed that settling well into school life and getting used to new routines were two important elements of a successful transition.

These aspects can be improved by encouraging children in the same class to work collaboratively and help each other even if they are not always together in the same lessons.

Most secondary schools are structured around a “form” system. Whilst this is usually used as a

“registration” group and as a PSHE group, heads of Year could use this time more constructively to enhance children’s social skills and self-esteem. A possible way forward may be to establish smaller “tutor/focus” groups within the “form”.

The most successful schools, as identified from the case studies, were those with very close links and co-ordination between primary and secondary schools. A variety of opportunities for induction, taster days and visits between schools appear to improve the transition experience for children. Choice Advisors targeting families that may need additional help seems to be helpful in the areas where they have been used, but the initiative was not yet widespread.

Curriculum interest and continuity

A child’s curriculum interest and continuity were two further indicators of a successful transition.

Children need to understand what is expected of them in secondary school, be prepared for the level and style of work, and be challenged to build on progress at primary school. This helps to ensure a growing interest in school and work. Teachers reported wanting more information and a better understanding of the different approaches to teaching between primary and secondary schools. Parents also want to see schools better preparing their children for the work expected of them in secondary school. Interestingly, the study found that children with health problems actually reported higher curriculum interest and continuity which may be related to focused support for these children at the point of transfer.

The main responsibility of the Local Authorities was the administrative process of admissions.

Their major concern was to provide good clear information to parents at an early stage, have statutory deadlines for the process met and have as few appeals as possible. However, where the Inspectorate/Advisory team had a stronger role/interest in the process, there was a higher likelihood of innovative curriculum practices and continuity (such as working on the same texts in Year 6 and Year 7). The

Inspectorate/Advisory service had a key role in promoting good communication and sharing good practice between clusters/pyramids of schools. The Inspectorate/Advisory service might be encouraged further in such practices and in taking a more active interest in the pupil’s experience of transition. Creating strategies and ideas for the

Inspectorate/Advisory service to help promote curriculum continuity could be beneficial for ensuring pupil’s interest and avoiding the learning ‘dip’ associated with Year 7.

To ensure that children’s transitions are successful (and improved where needed), all three areas (social adjustment, institutional adjustment and curriculum interest and continuity) need to be taken into account when

planning transition strategies at Local Authority and school levels.

Links with EPPSE Research

This research brief is based on a report which concentrates on the transition experiences of children who are taking part in the longitudinal

EPPSE project. There will be opportunities in the future to follow their progress over the next few years, and relate this to their early years.

As the EPPSE project will continue to track children’s development into KS3, the findings from the Transition project will complement the model of analyses for children’s developmental progress at age 14 (Year 9). This will be achieved by using the current findings on a sub-sample as potential predictors to explore cognitive and socio/behavioural development in

Year 9.

Further Information

Copies of the full report (DCSF-RR019) – priced £4.95 – are available by writing to DCSF

Publications, PO Box 5050, Sherwood Park,

Annesley, Nottingham NG15 0DJ.

Cheques should be made payable to “DFES

Priced Publications”

Copies of this Research Brief (DCSF-RB019 ) are available free of charge from the address above (Tel 0845 60 222 60). Research Briefs and Research Reports can also be accessed at: www.dcsf.gov.uk/research/

Further information about this research can be obtained from Dr Maria Evangelou, Department of Education, University of Oxford. Email: maria.evangelou@education.ox.ac.uk

The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department for Children Schools and

Families.