Influences on Children’s Development and Progress in Key Stage 2:

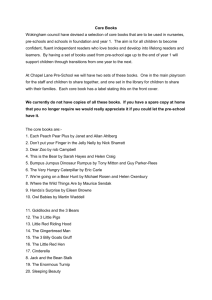

advertisement