ELAEIS GUINEENSIS RESPONSE TO LOCALIZED MARKETS IN SOUTH EASTERN GHANA, WEST AFRICA

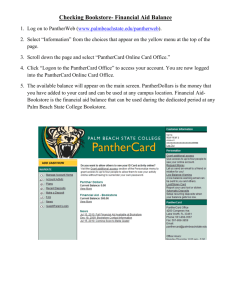

advertisement