THE USE AND POTENTIAL OF THE PITA PLANT, AECHMEA MAGDALENAE

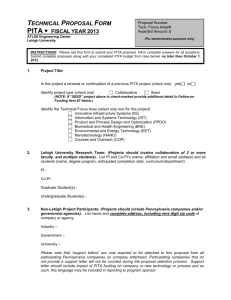

advertisement