Taxes and Benefits: The Parties’ Plans

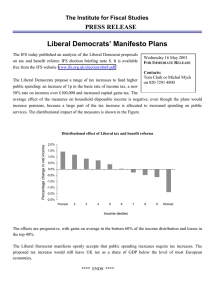

advertisement