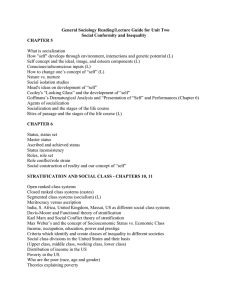

Living Standards, Inequality and Poverty: Labour’s Record

advertisement