Document 12831833

advertisement

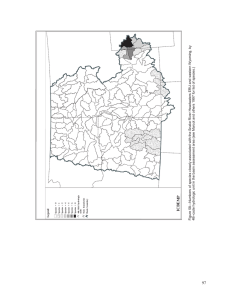

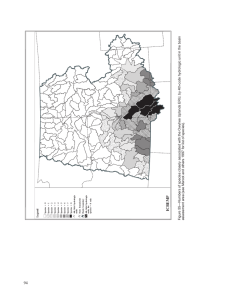

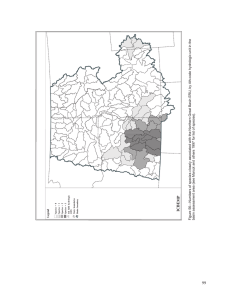

Figure 24—Recreation opportunities and metropolitan areas account for higher rates of population growth by county. 80 This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Text errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. 81 4.7 11.7 5.2 14.1 0.6 4.8 Construction Manufacturing SIC 242 Transportation 12.2* 4.2* 10.4 4.1 State & local Federal 7.8* 13.0* 14.6 23.2 3.9* 4.7* 14.0 18.8* 26.8 6.7 22.1* 4.3 2.8* 11.2 4.6 0.6 1.1 4.9* 4.5* 10.5 15.0* 27.4 6.2 21.4 5.7* 5.0* 11.5 5.4* 0.6 1.9* 7.3* 4.0 11.8 15.8* 27.2 5.5 21.9* 3.7 0.5 9.6 5.4* 0.8* 2.7* percent 14.2* 2.0 9.0 11.0 21.4 5.6 21.1 4.7 0.5 11.7 5.4* 0.3 4.7* 4.4* 12.2* 6.0* 13.4 17.8* 20.9 6.0* 10.3 16.3* 24.2 4.5 19.0 20.4 7.7* 4.5 2.7* 2.3* 4.9* 15.0* 3.5 0.0 2.6* Pendleton 12.6 5.1 0.4 2.5* Idaho Falls Twin Falls Boise 8.5* 4.1 11.1 15.1* 23.7 5.5 20.7 3.8 5.5* 16.0* 4.6 0.0 2.1* 1.8 4.6* 18.5* 23.1* 31.7* 6.8 20.3 6.0* 2.4* 4.4 3.5 1.5* 0.9 Redmond' Bend1 Butte Note: Farm employment is calculated as the difference between total employment and covered employment. Because it is calculated as a difference it includes rounding errors. 'Redmond-Bend is the portion of the Portland-Salem BEA region that is in the Basin. 2Timber and wood products, financial, insurance, and real estate industries. 2.2 2.7 16.4* 14.6 Government (all) Farm employment 11.9 25.0 28.4 4.6 Services 6.0 7.5 21.1 FIRE3 21.1 21.5 3.3 1.0* 11.3 4.2 0.2 4.4* Trade 4.3 2.5* 0.5 0.7 Mining 2.6* Basin average Tri-Cities Spokane! Missoula 1.1 Nation Agriculture services Industry Table 15—Employment in economic sectors of United States, the Basin, and Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) regions for 1995; asterisks indicate values above the national average. The non-metropolitan counties in the Basin have even better economic indicators than metropolitan counties. Per capita income is higher than the national average in all four states, although, except for Montana, growth rate is lower than the national average. Earnings per job in non-metropolitan counties are higher than the national average in the three Basin states, excluding Montana. The Basin's economy is small relative to the United States, accounting for only one percent of U.S. employment in 1995. The economic strengths of the Basin were characterized by identifying those economic activities within it that have a higher percentage of employment than the benchmark economy of the United States. Data for the percentage of employment in various economic sectors and areas (see table 15) suggest that the traditional notion that manufacturing is the driving sector of the Northwest economy, is too narrow (for example see Beuter 1995). The economic strengths of the Basin include agriculture and agricultural services. Mining and manufacturing, are less important to economies in the Basin than for the nation. Basin-wide, including both public and private lands, timber and wood products account for 2.5 percent of the jobs, cattle grazing accounts for 1.0 percent of the jobs, and mining accounts for 0.5 percent of the jobs. The percentage of jobs attributable to recreation is not shown here because the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) does not define it as an industry. In the discussion of recreation below, we calculate that 14.6 percent of jobs in the Basin are attributable to recreation. A more complex story emerges by looking at individual economic areas (called BEA regions; fig. 25) within the Basin. Agriculture is an economic strength in every region except the Butte BEA region. Mining in the Butte BEA region is double that of the national average, and it is important in the Idaho Falls BEA region as well. Manufacturing is a strong activity only in the Pendleton and Redmond-Bend BEA regions, and forest products and food 82 processing are important components of both. The importance of trade in each BEA region (except the Pendleton region) mirrors the United States. The same can be said about the service sector except there is more variability around the Basin. In the Boise BEA region, finance, insurance, and real estate are important activities. In several BEA regions construction and transportation are strong parts of the economy. The percentage of jobs supported by recreation is highest in the Idaho Falls (30%), Missoula (31%) and Redmond-Bend (25%) BEA regions. The past two decades have seen rapid population growth, and the evolution of what was a mature, resource-based, economy into a diverse economy oriented toward technology-based, transportation, and service sectors, with manufacturing, agriculture, and government sectors expected to decline over the next 50 years. Changes in current FS and BLM activities have little effect on the economy of the Basin. FS and BLM activities may have greater affect in specific communities, however. This study found there are 29 out of 539 censusrecognized places that may be sensitive to levels of public timber harvest14 (fig. 26). People hold both existence values and use values for ecosystem goods, functions, and conditions. Of the value provided society by the FS- and BLM-administered lands in the Basin now and by 2045, the existence of unroaded areas provides 47 and 41 percent; recreation provides 41 and 53 percent; timber provides 11 and 5 percent; and range provides less than 1 percent at both times. Market basket values per acre of FS- and BLMadministrated lands in the Basin are shown by ERU in figure 27. This market basket is only a subset of the measurable values of FS- and BLM-administered ecosystem goods, functions, and conditions: existence value of unroaded areas, recreation, timber, and range. This is the subset of ecosystem values (goods, function, and conditions) u The Component Assessment— Economic chapter defined isolated timber- dependent communities as those communities located more than 50 miles from another incorporated area with more than 10,000 people, and not located in either recreation or metropolitan counties. Figure 25—Economic subregions as defined by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. 83 that could be measured from information generated by the SIT; it is not comprehensive nor does it represent the total value of BLM and FS-administered lands in the Basin. It is an improvement on measuring only timber and range flows. Table 16 disaggregates the value of recreation for 12 recreational activities. Mining has long been an important activity in specific areas of FS- and BLM-administered land in the Basin. The Economics chapter of the Component Assessment has details on the three major components of the Basin mining industry: metallic minerals, phosphates, and aggregates (sand, gravel, and crushed stone) each of which has distinct economic characteristics. For metallic minerals and phosphate, activity is minor in spatial scale but significant in national and international commodity markets. Aggregate mining is more widely distributed throughout the Basin and lower in value; aggregates are primarily traded in local markets and used to construct buildings and infrastructure associated with human populations (photo 6). Although mining is important to jobs and income in a few communities in the Basin, when compared with a large, diverse, and growing economy, it represents a minor share of gross state product. Future minerals activity forecasts are in figure 28; the distribution depends on the locations of the deposits—quite specific for metals, minerals, and phosphate, but scattered for aggregates. Across the Basin, there are 180 mining and mineral processing sites in operation, 11 under development, and ten maintained on standby status; the value of production from these sites in 1992 was approximately $2.7 billion. Future activity will depend on a number of factors, most of them not directly affected by BLM or FS policy: the minerals present and their grade, global prices, extraction and remediation technology, and access. Counties differ in their reliance on timber and forage from FS- and BLM-administered lands. In some counties, FS- and BLM-administered lands provide a high proportion of the timber harvested Photo 6—Production of aggregates is a common mining activity on FS- BLM-administered lands. 84 Figure 26—The location of isolated timber-dependent communities within each BEA area. 85 Figure 27—Per acre market basket value of selected goods and services from FS- and BLM-administered lands. from all ownerships; in others, medium or low proportion (fig. 29). Similarly, forage from FSand BLM-administered lands is a high, medium, or low proportion of the total feed in each county (fig. 30). Those areas most reliant on Federal grazing are in the southern portion of the assessment area. These latter areas are dominated by rangeland vegetation types and large blocks of Federal ownership. Social15 Most of the social issues of interest relate to the rapid change occurring within the Basin. Changing economies are testing the ability of communities (both in the sense of "place" and in the sense of "communities of interest") to adapt to external changes. Increasing human populations focused primarily in metropolitan and high amenity areas are raising questions about the extent to which 15 Details are in the Component Assessment-Social chapter. 86 environmentally-based amenities are important in attracting population and business. Like people everywhere, the people of the Basin desire a higher quality of life. The Bureau of Census recognizes 476 communities within the project area, including 29 cities larger than 10,000 in population and 49 CensusDesignated Places, locations that are unincorporated but have an identity to the local population. Of the other 398 small rural communities, 68 percent are communities in the smallest size class of 1,500 or less. These range from 22 to 1,500 in size, with an average population of 520. In general, more-resilient communities tended to be larger, have an economy based on a mix of industries, be more autonomous, rated by residents as having a local government responsive to the public, and to have plans for dealing with change. 87 CONTINUED 89.28 5.43 5.87 9.28 5.09 0.60 0.04 0.05 0.34 0.16 35.49 Winter sports Camping Trail use Motor viewing Viewing wildlife Motor boating Non motor Off road vehicle Snow Mobile Total by ERU 0.15 4.20 Day use 0.14 1.21 0.19 12.24 5.44 5.40 6.33 14.88 12.80 6.96 3.22 Hunting 23.57 1.22 10.00 0.04 0.02 0.06 0.23 0.39 0.01 10.56 7.19 0.02 0.07 0.02 0.06 0.05 0.02 0.11 1.85 0.48 24.29 0.06 0.07 0.04 0.06 1.07 0.68 2.53 0.48 0.32 0.34 0.72 3.29 0.24 0.34 0.86 2.80 3.02 0.68 0.19 0.50 0.31 5.59 6.02 1.47 6.58 0.39 0.80 1.58 0.36 1.48 2.26 1.44 2.05 16.18 0.05 0.07 0.21 0.12 0.46 1.01 1.24 1.52 1.35 2.35 4.44 3.34 0.25 0.18 0.25 0.17 0.98 1.14 2.03 1.83 2.31 3.50 14.29 5.16 42.87 32.09 0.16 0.33 0.27 0.41 0.82 2.33 2.84 3.44 2.24 6.89 15.56 7.57 Dollars per acre (in 1994 dollars) - 8.32 0.01 0.05 0.03 0.38 0.13 0.17 0.32 0.49 1.10 0.29 2.86 2.50 10.95 0.02 0.11 0.04 0.10 0.64 0.29 0.58 0.64 2.11 0.71 2.82 2.88 23.58 0.20 0.11 0.77 0.32 0.68 0.92 2.62 1.41 5.68 3.13 4.03 3.71 1.72 2.51 39.37 0.14 0.31 0.52 0.77 1.26 21.62 0.07 0.12 0.21 0.25 0.88 0.98 1.81 2.78 2.25 2.65 2.77 4.97 5.18 5.78 6.08 8.90 8.07 ERU1 ERU 2 ERU 3 ERU 4 ERU 5 ERU 6 ERU 7 ERU 8 ERU 9 ERU 10 ERU 11I ERU 12! ERU 13 Fishing Activity Average by activity Table 16—Net economic value (willingness to pay) of current recreation activities on ' FS-BLM lands, by ecological reporting unit (ERU).