UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL1010: INTRODUCTION TO EUROPEAN PREHISTORY 2015-16

advertisement

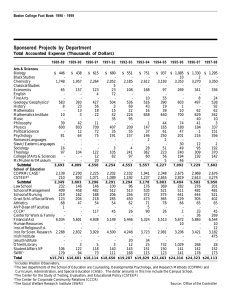

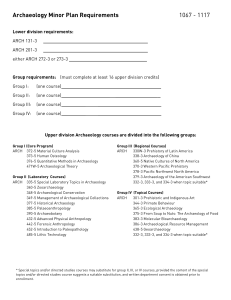

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL1010: INTRODUCTION TO EUROPEAN PREHISTORY 2015-16 Year 1 Option, 0.5 unit Turnitin Class ID: 2970081 Turnitin Password: IoA1516 Co-ordinator: STEPHEN SHENNAN s.shennan@ucl.ac.uk Room 407 Telephone number: 020-7679-4739 Room 410, Term II, Mondays 11:00 – 13:00 1 1 OVERVIEW Short description Europe is the smallest of the five continents, only a peninsula of Eurasia in geographical terms. It is not a clearly defined area and open to influences from all directions. There are several different macro-regions, but their boundaries shift with changing climates and modes of production. An unequal distribution of mineral resources, diverse and flexible ecologies, major topographic barriers, and distinct topographic axes of communication add to the diversity and unique aspects of past and present Europe, which is the area with the longest tradition of prehistoric research and the densest network of known sites. This course assesses prehistoric Europe from the first peopling of the continent about 1.2 million years ago until the first century AD when the expanding empire of Rome absorbed parts of the continent into its boundaries. Major topics of the course will be: - the earliest occupation of Europe; - European Neanderthals; - the arrival of modern humans in Europe; - late Pleistocene and early Holocene hunter-gatherers of Europe; - the origins of farming and its spread across Europe; - the emergence and development of social hierarchies and long-distance connections; - the growth of states and urban centres in the Mediterranean and Europe north of the Alps; - the impact of Rome on European societies. 2 Week-by-week summary Date 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11/01/2016 18/01/2016 25/01/2016 01/02/2016 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 08/02/2016 15-19. Feb 22/02/2016 29/02/2016 07/03/2016 14/03/2016 18 19 20 21/03/2016 Topic lecturer Part 1: introducing Europe Introduction: course organisation and objectives. Prehistoric Europe and its time-scales Part 2: hunters and gatherers The peopling of Europe: the early evidence The European Neanderthals The arrival of modern humans Late Pleistocene hunters and post-glacial developments Practical - handling session Mesolithic hunters, gatherers and fishers Part 3: early farming communities The origins of farming and the spread of agriculture across Europe The Neolithisation of North-Western Europe Early metals and rising inequality READING WEEK (NO TEACHING) The creation of supra-regional networks: Corded Ware, Bell Beakers (and Indo-Europeans?) Part 4: complex agrarian societies The beginnings of the Bronze Age Farmers and chieftains of Bronze Age Europe The rise of states in the Mediterranean The Iron Age north of the Alps The Iron Age in the British Isles Nomads of the Steppe Zone from the early Bronze Age to the Scythians Greeks, Phoenicians and others across the Mediterranean The impact of Rome on European societies Practical, handling session Stephen Shennan (SJS) Mark Roberts (MR) MR MR MR MR Marc Vander Linden (MVL) SJS SJS SJS SJS SJS SJS Borja Legarra Herrero MVL MVL Ulrike Sommer (US) Corinna Riva Kris Lockyear SJS/US Basic texts Cunliffe, B. (ed.), 1994. The Oxford Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) Cunliffe, B. 2008. Europe between the oceans: themes and variations: 9000 BC-AD 1000. New Haven: Yale University Press. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN Core reading for the second half of the course. Bogucki, P. Crabtree, P. M. 2004. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000. Encyclopedia of the Barbarian world. London, Thompson/Gale. INST ARCH DA 100 BOG Methods of assessment This course is assessed by means of: - two pieces of coursework, which each contribute 50% to the final grade for the course. 3 Teaching methods This handbook contains the basic information about the content and administration of the course. Additional subject-specific reading lists and individual session handouts may be given out at appropriate points in the course. The Course Moodle is the best source of up-to date information and should be consulted if in doubt. If students have queries about the objectives, structure, content, assessment or organisation of the course, they should consult the Course Co-ordinator (Stephen Shennan). This course will be taught by lectures, seminars and two practicals (material handling sessions). The lectures will introduce the main issues and themes of the course, and will be concluded with brief discussions. The material handling sessions will provide students with the opportunity of studying typical artefacts from each of the main periods covered by the course. These artefacts will come from a broad range of European contexts and allow students to develop skills of comparative analysis of stylistic types, various technologies, and different raw materials. Workload There will be 18 hours of lectures and 2 hours of practical sessions for this course. Students will be expected to undertake around 48 hours of reading for the course, plus 120 hours preparing for and producing the assessed work. This adds up to a total workload of some 188 hours for the course. 2 AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND ASSESSMENT Aims This course aims at introducing students to the main chronological divisions of prehistoric Europe, and related questions. Particular attention will be paid to the changing nature of the evidence, and how this shapes our interpretations of the past. Objectives On successful completion of this course a student should: Be familiar with the main chronological divisions of European prehistory, and corresponding social and economic developments. Recognise main artefact types, settlement and funerary practices relating to each makor periods and regions studied Have a basic understanding of the major interpretative themes relating to prehistoric Europe Learning Outcomes On successful completion of the course, students should be able to demonstrate/have developed: application of acquired knowledge, and critical assessment of existing methods and interpretations writing skills, including structuring and articulating arguments based on archaeological evidence Coursework Assessment tasks All students must submit two standard essays (2,375 – 2,625 words each), one for section 1, one for section 2 - section 1 (submission deadline: Tuesday 23 February 2016) - section 2 (submission deadline: Thursday 28 April 2016) 4 SECTION 1 Essay 1 Evaluate the evidence for big-game hunting (as opposed to scavenging) in the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic of Europe. Suggested reading Binford, L. R. 1981. Bones: ancient men and modern myths. Orlando, Academic Press. INST ARCH BB 3 BIN (The book that started the discussion) Mellars, P. 1996. The Neanderthal Legacy: an archaeological perspective from Western Europe. Princeton, Princeton University. Chapter 7. INST ARCH. DA 120 MEL Roberts, M. B. 1997/98. Boxgrove: Palaeolithic hunters by the seashore. Archaeology International 1, 8-13. INST ARCH. PERS Scott, K. 1980. Two hunting episodes of Middle Palaeolithic age at La Cotte de Saint Brelade, Jersey (Channel Islands). World Archaeology 12, 137-52. NET Stiner, M. C. N., Munro, D., Surovell, T. A. 2000. The tortoise and the hare. Small-Game use, the broadspectrum revolution and Palaeolithic demography. Current Anthropology 41, 39-73. Net Thieme, H. 1997. Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany. Nature 385, 807-810. NET Villa, P. 1990. Torralba and Aridos: elephant exploitation in Middle Pleistocene Spain. Journal of Human Evolution 19, 299-310. NET see also Richards, M. B. et al. 2000. Neanderthal diet at Vindija and Neanderthal predation: The evidence from stable isotopes. Proceedings National Academy Science USA 97/13, 7663–7666. Thieme, H. (ed.), 2007. Die Schöninger Speere: Mensch und Jagd vor 400 000 Jahren. Stuttgart, Theiss. INST ARCH DAD 12 Qto THI excellent illustrations and up-to date information Villa, P., Lenoir, M. 2009. Hunting and hunting Weapons of the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic of Europe. In: Hublin, J.-J., Richards, M. P. (eds.), The Evolution of hominin Diets: Integrating Approaches to the Study of Palaeolithic Subsistence. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. New York, Springer, 59-85. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4020-9699. Essay 2 Outline the process of colonization of Europe by the anatomically modern humans and the extinction of Neanderthals. Suggested reading d'Errico, F. 2003. The invisible frontier. A multiple species model for the origin of behavioural modernity. Evolutionary Anthropology 12, 188-202. ONLINE Hoffecker, J. F. 1999. Neanderthals and modern humans in Eastern Europe. Evolutionary Anthropology 7/4, 129-141. ONLINE *Mellars, P. 1994. The Upper Palaeolithic revolution. In: Cunliffe, B. (ed.) The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 42-78. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) 5 Mellars, P. 2004. Neanderthals and the modern human colonization of Europe. Nature 432, 461-465. ONLINE Mellars, P. et al. 1999. The Neanderthal problem continued. Current Anthropology 40/3, 341-364. ONLINE Zilhão, J., d'Errico F.1999. The chronology and taphonomy of the earliest Aurignacian and its implications for the understanding of Neandertal extinction. Journal of World Prehistory 13/1, 1-68. INST ARCH Pers Essay 3 Outline the arguments for the existence of social complexity during the European Mesolithic Suggested reading Bailey, G., Spikins, P. (eds) 2008. Mesolithic Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. INST ARCH DA 130 BAI (edited volume, with several contributions directly discussing the issue of 'complex hunter-gatherers') Conneller, C., Milner, N., Taylor, B & Taylor, M. 2012. Substantial settlement in the European Early Mesolithic: new research at Star Carr. Antiquity 86: 1004-1020. Conneller, J., Warren, G. (eds) 2006. Mesolithic Britain and Ireland: New Approaches. Stroud, Tempus. INST ARCH DAA 130 CON, ISSUE DESK IOA CON 7 Kozłowski, St. K. 2009. Thinking Mesolithic. Oxford, Oxbow. INST ARCH DA Qto KOZ SECTION 2 Essay 4 Outline the arguments for or against the role of local foragers in the introduction of farming practices in Europe. Pick one or more specific areas, like south-eastern, central, Mediterranean or north-western Europe. See reading lists for lectures 8 and 9 Essay 5 Evaluate the evidence for hierarchies and social inequality in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe. Are there any long-term trends? See reading list for lecture 11 Essay 6 How convincing is the evidence for prehistoric urbanism in Iron Age Europe? See reading list for lectures 15 and 16 If students are unclear about the nature of an assignment, they should discuss this with the Course Coordinator. Students are not permitted to re-write and re-submit essays in order to try to improve their marks. However, the Course Co-ordinator is willing to discuss an outline of the student's approach to the assignment, provided this is planned suitably in advance of the submission date. 6 Word limits The following should not be included in the word-count: title page, contents pages, lists of figure and tables, abstract, preface, acknowledgements, bibliography, lists of references, captions and contents of tables and figures, appendices. Word-counts for each essay will be between 2,375-2,625 words Penalties will only be imposed if you exceed the upper figure in the range. There is no penalty for using fewer words than the lower figure in the range: the lower figure is simply for your guidance to indicate the sort of length that is expected. 3 SCHEDULE AND SYLLABUS Teaching schedule Lectures will be held 11:00-13:00 on Mondays, in room 410. Practical sessions will be held 11:00-13:00 on Mondays, in room 410. Syllabus I. INTRODUCING EUROPE 1. Stephen Shennan: Introducing prehistoric Europe What is Europe, how has it been defined, and why? There are numerous different definitions of the boundaries of Europe, and even the concept of ‘Europe’ itself is relatively recent. The lecture will begin by highlighting some of these different views by looking at the climatic and geographic variation which exists within ‘Europe’, followed by a short appraisal of the cultural, linguistic and political evolution of the concept. Implications for the study of prehistoric Europe will be considered. Reading: Cunliffe, B. (ed.), 1994. The Oxford Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, p. 1- 3 (introduction) and table 14. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) Gramsch, A. 2000. 'Reflexiveness' in archaeology, nationalism, and Europeanism. Archaeological Dialogues 7/1. INST ARCH Pers and NET Kristiansen, K. 2008. Do we need the ‘archaeology of Europe’? Archaeological Dialogues 15/1, 5-25. ONLINE Renfrew, C. 1994. The identity of Europe in prehistoric archaeology. Journal of European Archaeology 2/2, 153173. INST ARCH Pers Schnapp, A. 1996. The discovery of the past: the origins of archaeology. London, British Museum Press. INST ARCH AG SCH Additional reading: Ascherson, N. 1995. Black Sea. Chapter 2 (but the whole book is worth reading). SSEES. Misc.IX.a ASC. On order for IoA Library. Biehl, P., Gramsch, A., Marciniak, A. 2002. Archaeologies of Europe: Histories and identities, an introduction. In: Biehl, P. Gramsch, A., Marciniak, A. (eds), Archaeologies of Europe. Münster, Waxmann, 25-34. INST ARCH AF BIE 7 Graves-Brown, P., Jones, S., Gamble C. (eds) 1995. Cultural Identity and Archaeology: The Construction of European Communities. New York, Routledge. INST ARCH BD GRA (ISSUE DESK) Pluciennik, M. 1998. Archaeology, archaeologists and 'Europe'. Antiquity 72, 816-824. INST ARCH PERS and NET Pounds, N. J. G. 1990. A Historical Geography of Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. GEOGRAPHY K 60 POU Rowlands, M. 1987. Europe in Prehistory. Culture and History 1, 63-78. Stores II. HUNTERS AND GATHERERS 2. Mark Roberts: The peopling of Europe: the early evidence The first areas of Europe to be colonised were in the Mediterranean belt of southern Europe, with sites such as Orce in southern Spain dating back to over 1myr. The earliest widespread settlement in the more temperate latitudes of central and western Europe dates to post 0.6 Million years. The rare hominin fossils from Lower Palaeolithic sites have been attributed to Homo erectus, H. antecessor and H. heidelbergensis. Who were these people? How did they survive? We will consider the evidence, which may provide answers to these questions. Essential reading Foley, R. Lahr, M. M. 2003. On stony ground: lithic technology, human evolution, and the emergence of culture. Evolutionary Anthropology 12, 109-122. ONLINE. Roebroeks, W. 2006. The human colonisation of Europe: where are we? Journal of Quaternary Science 21, 425435. ONLINE Additional reading Abate, E. and Sagri, M. 2012. Early to Middle Pleistocene homo dispersals from Africa to Eurasia: geological, climatic and environmental constraints. Quaternary International 267, 3-19. Ashton, N.M. and Lewis, S.G. 2012. The environmental contexts of the earliest occupation of north-west Europe: the British Palaeolithic record. Quaternary International 271, 50-64. Azarello, M. et al., 2009. The lithic industry of the Early Pleistocene site of Pirro Nord (Apricena South Italy): the evidence of human occupation between 1.3 and 1.7 Ma. L’Anthropologie 113, 47-58. Balter, M. 2014. The killing ground. Science 344 (6188), 1080-1083. DOI:10.1126/science.344.6188.1080 Carbonell, E. Ramos, R.S., Rodríguez, P.X., Mosquera, M., Ollé, A., Vergès, J.M., Martínez-Navarro, B. and Bermúdez de Castro, J.M. 2010. Early hominid dispersals: A technological hypothesis for “out of Africa”. Quaternary International 223-224, 36-44. Carbonell, E., Rodríguez, X. P. 2006. The first human settlement of Mediterranean Europe. Comptes Rendus Palevolution 5, 291-298. Online Crochet, J-Y. et al. 2009. Une nouvelle faune de vertebras contintaux, associée à des artefacts dans le Pléistocène inférieur de l’ Hérault (Sud de la France), vers 1.57 Ma. Comptes Rendus Palevol 8, 725-736. Dennel, R., Martinón-Torres, M. and Bermúdez de Castro, J.M. 2010. Out of Asia: the initial colonisation of Europe in the Early and Middle Pleistocene. Quaternary International 223-224, 439. Dennel, R.W. and Roebroeks, W.M. 2005. Out of Africa: An Asian perspective on early human dispersal from Africa. Nature 438: 1099-1104. Despriée, J. et al., 2006. Une occupation humaine au Pléistocène inférieur sur la bordure du Massif Central. Comptes Rendus Palevol 5, 821-828. Gamble, C. 1999. The Palaeolithic societies of Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapters 4 and 5. INST ARCH DA120 GAM (ISSUE DESK) Leroy, S.A.G., Arpe, K. and Mikolajewicz, U. 2010. Vegetation context and climatic limits of the Early Pleistocene hominin dispersal in Europe. Quaternary Science Reviews 29: 1-16. 8 Lycett, S.J. 2009. Understanding ancient hominin dispersals using artefactual data: a phylogeographic analysis of Acheulean handaxes. PLoS ONE 4 (10)/e7404: 1–6. Lycett, S.J. and von Cramon-Taubadel, N. 2008. Acheulean variability and hominin dispersals: a modelbound approach. Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (3), 553–562. Mancini, M. 2012. The genus Homo from Africa to Europe: evolution of terrestrial ecosystems and dispersal routes. Quaternary International 267, 1-2. Messager et al., 2011. Palaeoenvironments of early hominins in temperate and Mediterranean Eurasia: new palaeobotanical data from Palaeolithic key sites and synchronous natural sequences. Quaternary Science Reviews 30, 1439-1447. Moncel, M-H., 2010. Oldest human expansions in Eurasia: favouring and limiting factors. Quaternary International 223-224, 1-9. Mounier, A., Marchal, F. and Condemi, S. 2009. Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible. Journal of Human Evolution 56, 219–246. Palumbo, M.R. 2013. What about causal mechanisms promoting early hominin dispersal in Eurasia? A research agenda for answering a hotly debated question. Quaternary International 295, 13-27 Parés, J.M. et al., 2012. New views on an old move: hominin migration into Eurasia. Quaternary International. Available to download not yet published. Parfitt, S.A., et al. 2010. Early Pleistocene human occupation at the edge of the boreal zone in northwest Europe. Nature 466, 229-233. Preece, R.C. and Parfitt, S.A. 2012. The Early and early Middle Pleistocene context of human occupation and lowland glaciation in Britain and northern Europe. Quaternary International 271, 6-28. Rodríguez, J. et al. 2013. Mammalian palaeobiogeography and the distribution of Homo in Early Pleistocene Europe. Quaternary International 295, 48-58. Rolland, N. 1998. The Lower Palaeolithic settlement of Eurasia, with special reference to Europe. In: Petraglia, M., Korisettar, D. (eds.), Early human behavior in global context. London, Routledge, 187-220. INST ARCH BC 120 PET van der Made, J. and Mateos, A., 2010. Longstanding biogeographic patterns and the dispersal of early Homo out of Africa and into Europe. Quaternary International 223-224, 195-200. van der Made, J., 2011. Biogeography and climatic change as a context to human dispersal out of Africa and within Eurasia. Quaternary Science Reviews 30, 1353-1367. See also Bosinski, G., Lordkipanidze, D., Weidemann, K. 1995. Der altpaläolithische Fundplatz Dmanisi (Georgien, Kaukasus). Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums 42, 1995, 21–203. INST ARCH PERS Carbonell et al. 2010. Cannibalism as a palaeoeconomic system. Current Anthropology, 51 (4). Carbonelll, E. 2008. The first hominin of Europe. Nature 452, 465-469. http://www.nature.com/news/2008/080326/full/news.2008.691.html. Video of Atapuerca discoveries: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7313005.stm Eren, M.I., Roos, C.I., Story, B., von Cramon-Taubadel., N. and Lycett, S.J. 2014. The role of raw material differences in stone tool shape variation: an experimental assessment. Journal of Archaeological Science. 49, 472–487. Gabunia, L. K. et al. 2000. A. Earliest Pleistocene Hominid Cranial Remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, Geological Setting, and Age. Science 288, 1019–1025. Gaudzinski S, Turner E, Anzidei AP, Alvarez-Fernández E, Arroyo-Cabrales J, et al. 2005 The use of proboscidean remains in every-day Palaeolithic life. Quaternary International 126–128, 179–194. Hewitt, G. 1996. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 58: 247-76. Richards, M.P. 2002. A brief review of the archaeological for Palaeolithic and Neolithic subsistence. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 56, 1-12. 9 Spikins, P. A., Rutherford, H.A. and Needham, A.P., 2010. From hominity to humanity: compassion from the earliest archaics to modern humans. Time and Mind: The Journal of Human Consciousness and Compassion 3(3), 303-326. Stewart, J.R and Stringer, C.B., 2012. Human evolution out of Africa: the role of refugia and climate change. Science 335, 1317-1321. Stewart, J.R. et al. 2009. Refugia revisited: individualistic responses of species in space and time. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277 (1682), 661-671. Stringer, C.B., 2014. Britain: one million years of the Human Story. London: The Natural History Museum. Villa, P, & Lenoir M. 2009. Hunting and hunting weapons of the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic of Europe. In J-J Hublin & M.P. Richards (eds.) The evolution of hominin diets. Dordrecht: Springer. 59-85. Villa, P., and Roebroeks, W. 2014. Neandertal Demise: An Archaeological Analysis of the Modern Human Superiority Complex. PLoS ONE 9(4): e96424. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096424 Wadley, L. et al. 2009. Implications for complex cognition from the hafting of tools with compound adhesives in the Middle Stone Age, South Africa. PNAS 106 (24), 9590-9594. Wilkins, J. et al. 2012. Evidence for early hafted hunting technology. Science 338, 942-946. 3. Mark Roberts: The European Neanderthals Neanderthals were a species restricted to Europe and the Near East. They evolved from more archaic European populations, and were anatomically adapted to the cold conditions of the European Pleistocene from ca. 300,000 to 30,000 years ago. The specific anatomical backgrounds of Neanderthals and their varied cultural features will be revised in this lecture. Essential reading Hayden, B. 1993. The cultural capacities of Neanderthals: a review and re-evaluation. Journal of Human Evolution 24, 113-146. ONLINE Stringer, C. Gamble, C. 1993. In Search of Neanderthals, solving the puzzle of human origins. London, Thames and Hudson. Especially chapters 4, 7. INST ARCH BB1 STR (ISSUE DESK) Additional reading Adler, D.S. et al. 2014. Early Levallois technology and Lower to Middle Palaeolithic transition in the Southern Caucasus. Science 345 (6204), 1609-1613. Barshay-Szmidt, C.C., Eizenberg, L. and Deschamps, M. 2012. Radiocarbon (AMS) dating the Classic Aurignacian, Proto-Aurignacian and Vasconian Mousterian at Gatzarria Cave (Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France), PALEO [En ligne], paleo.revues.org/2250. Caron, F. et al. 2011. The reality of Neanderthal symbolic behaviour at the Grotte du Renne, Arcy-sur Cure, France. PLoS One 6(6): e21545. doi10.1371/journal.pone.0021545. Dediu, D. and Levinson, S.C. 2013. On the Antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neanderthal linguistic capacities and its consequences. Frontiers in Psychology 4, 1-17. Endicott, P., Ho, S.Y. W. and Stringer, C.B. 2010. Using genetic evidence to evaluate four anthropological hypotheses for the timing of Neanderthal and modern human origins. Journal of Human Evolution 59, 87-95. Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S. and Kindler, L. 2012. Research perspectives for the study of Neanderthal subsistence strategies based on the analysis of archaeozoological assemblages. Quaternary International. 247, 59-68. Hardy, B.L. 2010. Climatic variability and plant food distribution in Pleistocene Europe: implications for Neanderthal diet and subsistence. Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (5-6), 662-679. Henry, A.G., Brooks, A.S. and Piperno, D.R. 2010. Microfossils in calculus demonstrate the consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets (Shanidar III, Iraq; Spy I & II, Belgium). PNAS Mellars, P. 1996. The Neanderthal Legacy: an archaeological perspective from Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press. INST ARCH DA120 MEL (ISSUE DESK) 10 Pettitt, P. B. 2000. Neanderthal lifecycles: developmental cycles and social phases in the lives of the last archaics. World Archaeology 31/3, 351-66. ONLINE Pettitt, P. B. 2002. The Neanderthal dead: exploring mortuary variability in Middle Palaeolithic Eurasia. Before Farming 4, 1-26. ONLINE Rae, T.C., Koppe, T. and Stringer, C.B., 2011. The Neanderthal face is not cold adapted. Journal of Human Evolution 60, 234-239. Richter, J. et al. 2012. Contextual areas of early Homo sapiens and their significance for human dispersal from Africa into Eurasia between 200ka and 70ka. Quaternary International 274, 5-24. 4. Mark Roberts: The arrival of modern humans The Upper Palaeolithic from 40,000-12,000 years ago spans the last great Ice Age. At the beginning of this period Neanderthal populations were replaced by modern humans in Europe. This biological change is accompanied by significant changes in human behaviour affecting the social, economic, ritual and artistic activities of these groups who explored all but the most northerly areas of Europe. Essential reading Mellars, P. 1994. The Upper Palaeolithic Revolution. In: Cunliffe, B. (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 42-78. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) Mellars, P. 2004: Neanderthals and the modern human colonization of Europe. Nature 432, 461-465. ONLINE Additional reading d'Errico, F. 2003. The invisible frontier. A multiple species model for the origin of behavioural modernity. Evolutionary Anthropology 12, 188-202. ONLINE Mellars, P. et al. 1999. The Neanderthal problem continued. Current Anthropology 40/3, 341-364. ONLINE Zilhão, J. 2006. Neandertals and Moderns mixed, and it matters. Evolutionary Anthropology 15, 183-195. ONLINE 5. Mark Roberts: Late Pleistocene hunters and post-glacial developments During the Upper Palaeolithic period several cultures were appearing, usually associated with symbolic representations considered as the earliest obvious artistic manifestations. This lecture will explore the relationships between the Upper Palaeolithic art and Late Pleistocene human adaptations and, finally, the cultural answers to the beginning of the current warm inter-glacial (the Holocene) and the appearance of the Mesolithic. Essential reading Bahn, P. Vertut, J. 1997. Journey through the Ice Age. London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson. INST ARCH BC300 BAR (ISSUE DESK) Lawson, A. J. 2012. Painted caves: Palaeolithic rock art in Western Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press. INST ARCH DA 120 LAW Additional reading Anikovich, M.V., et al. 2007. Early Upper Palaeolithic in Eastern Europe and Implications for the Dispersal of Modern Humans. Science 315, 223-226. Banks, W.E., d’Errico, F. and Zilhāo, J. 2013. Human-climate interaction during the early Upper Palaeolithic: testing the hypothesis of an adaptive shift between the proto-Aurignacian and the early Aurignacian. Journal of Human Evolution 64. 39-55. Bar-Yosef, O. and Bordes, J-G., 2010. Who were the makers of the Châtelperronian culture? Journal of Human Evolution 59, 586-593. Bar-Yosef, O., 2002. The Upper Palaeolithic Revolution. Annual Review of Anthropology 31, 363-393. Clottes, J. 1996. Thematic changes in Upper Palaeolithic art: a view from Grotte Chauvet. Antiquity 70, 27688. Online 11 Cuenca-Bescós, G. et al. 2012. Relationship between Magdalenian subsistence and environmental change: the mammalian evidence from El Mirón (Spain). Quaternary International 272-273, 125-137. Dayet, L., d’Errico, F. and Garcia-Morena, R. 2014. Searching for consistencies in Châtelperronian pigment use. Journal of Archaeological Science 44, 180-193. Dinnis, R., 2012. The archaeology of Britain’s first modern Humans. Antiquity 86 (333), 627-641. Eren, M.I., Greenspan, A. and Sampson, G.C. 2008. Are Upper Paleolithic blade cores more productive than Middle Paleolithic discoidal cores? A replication experiment. Journal of Human Evolution. 55, 952-961. Gamble, C. 1991. The social context of European Palaeolithic art. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 57, 3-15. INST ARCH Pers Krause, J., et al. 2010. The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia. Nature 464, 894-897. Miller, R. 2012. Mapping the expansion of the Northwestern Magdalenian. Quaternary International 272-273, 209-230. Niven, L. 2007. From carcass to cave: large mammal exploitation during the Aurignacian at Vogelherd, Germany. Journal of Human Evolution 53, 362-382. Otte, M. 2012. Appearance, expansion and dilution of the Magdalenian civilisation. Quaternary International 272-273, 354-361. Pettitt, P. and White, M.J., 2013. The British Palaeolithic: human societies at the edge of the Pleistocene world. Routledge. Pitulko, V.V., et al. 2012. The oldest art of the Eurasian Arctic: personal ornaments and symbolic objects from Yana RHS, Arctic Siberia. Antiquity 86 (333), 642-659. Schwendler, R.H. 2012. Diversity in social organisation across Magdalenian Western Europe ca. 17-12,000 BP. Quaternary International 272-273, 333-353. Straus, L., Leesch, D. and Terberger, T. 2012. The Magdalenian settlement of Europe: an introduction. Quaternary International 272-273, 1-5. Tolksdorf, J.F., et al. 2009. The Early Mesolithic Haverbeck site, Northwest Germany: evidence for Preboreal settlement in the Western and Central European Plain. Journal of Archaeological Science 36, 1466-1476. White, R. 2003. Prehistoric art: the symbolic journey of humankind. New York, Harry N. Abrams. INST ARCH BC 300 WHI See also: Anikovich, M. 1992. Early Upper Palaeolithic Industries of Eastern Europe. Journal of World Prehistory 672, 205-245. Beresford, M. 2012. Beyond the ice: Creswell Crags and its place in a wider European context. Oxford, Archaeopress. On order Desdemaines-Hugon, Chr. 2010. Stepping-stones: a journey through the Ice Age caves of the Dordogne. New Haven, Yale University Press. INST ARCH DAC 22 DES 6. Mark Roberts, Stephen Shennan: practical, handling session You will be divided into small groups in order to study and handle a range of artefacts from the Collection of the Institute of Archaeology relating to the Stone Ages. You may want to revise the basic types of stone tools and the types of tools typical for each period of the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic. Bring your notes and handouts! 7. Marc Vander Linden: Mesolithic hunters, gatherers and fishers The Mesolithic covers the period between the end of the Pleistocene, and before the introduction of agriculture. In this sense, it is best defined as the period corresponding to Holocene huntergs, gathers and 12 fishers. The period is characterised by a much reduced home-range compared to the Palaeolithic and an increased reliance on small game hunting and gathering. In North-Western Europe, there is a marked preference for using rich coastal ecosystems, whilst the nature of the evidence across much of continental Europe is very changing. Esssential reading Mithen, S. J. 1994. The Mesolithic Age. In: Cunliffe, B. (ed.) The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 79-135. INST ARCH D A 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) Additional reading Bailey, G. and Spikins, P. (eds) 2008. Mesolithic Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. INST ARCH DA 130 BAI (Chapters on individual countries and areas) Conneller, J., Warren, G. (eds) 2006. Mesolithic Britain and Ireland: New Approaches. Stroud, Tempus. INST ARCH DAA 130 CON, ISSUE DESK IOA CON 7 Kozłowski, St. K. 2009. Thinking Mesolithic. Oxford, Oxbow. INST ARCH DA Qto KOZ See also: Bell, M. 2007. Prehistoric coastal communities: the Mesolithic in western Britain. CBA Research Report 149. York: Council for British Archaeology. INST ARCH DAA Qto Series COU 149 Conneller, J. 2005. Moving beyond sites: Mesolithic technology in the landscape. In: Milner, N. J., Woodman, P. (eds.), Mesolithic Studies at the Beginning of the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, Oxbow, 42-55. INST ARCH DA 130 MIL Finlay, N. et al. (eds) 2009. From Bann Flakes to Bushmills: papers in honour of Professor Peter Woodman. Oxford, Oxbow. INST ARCH DAA 100 FIN Gaffney, V., Fitch, S. Smith, D. 2009. Europe's lost world: the rediscovery of Doggerland. York: Council for British Archeology. INST ARCH DAA Qto Series COU 160 Larsson, L. et al. (eds) 2003. Mesolithic on the move: papers presented at the Sixth International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, Stockholm 2000. Oxford, Oxbow, 2003. INST ARCH DA Qto LAR McCartan, S. et al. (eds) 2009. Mesolithic horizons: papers presented at the Seventh International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, Belfast 2005. Oxford, Oxbow Books. INST ARCH DA Qto CAR Online journal Mesolithic miscellany https://sites.google.com/site/mesolithicmiscellany/ (Provides reports and up-to-date assessments of regional evidence and thematic issues) III: EARLY FARMING COMMUNITIES 8. Stephen Shennan: The origins of farming and the spread of agriculture across Europe Archaeologists have paid extensive attention to the transition from an economy based on foraging to one based on farming, what Gordon Childe labelled the ‘Neolithic Revolution’. The diffusion of farming practices across Europe, from southeast to northwest, took some three thousand years from c. 7000 to c. 4000 BC. The lecture will consider the nature and characteristics of the earliest farming societies in Mediterranean, Southeast, and Central Europe. Essential reading Barker, G. 2006. The agricultural revolution in prehistory: why did foragers become farmers? Oxford, Oxford University Press. Chapter 8 on Europe. INST ARCH HA BAR and ISSUE DESK IOA BAR 24 Shennan, S.J. 2009. Evolutionary Demography and the Population History of the European Early Neolithic. Human Biology 81, 339-355. ONLINE Whittle, A. 1994. The first farmers. In: Cunliffe, B. (ed), The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 136-166. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) 13 Zeder, M. A. 2008. Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean basin: origins, diffusion, and impact. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105, 11597–11604. ONLINE Additional reading Bentley, A., M. O’Brien, K. Manning, S. Shennan 2015. On the relevance of the European Neolithic. Antiquity 89: 1203–1210 Bernabeu Auban, J., O. García Puchol, M. Barton, S. McClure and S. Pardo Gordo 2015. Radiocarbon dates, climatic events, and social dynamics during the Early Neolithic in Mediterranean Iberia. Quaternary International in press. ONLINE Bogaard, A. 2004. Neolithic farming in central Europe. London, Routledge. INST ARCH DA 140 BOG Bollongino, R. et al. 2013. 2000 Years of Parallel Societies in Stone Age Central Europe. Science 342, 479-481. ONLINE Colledge, S., Conolly, J. (eds.) 2007. The origins and spread of domestic plants in southwest Asia and Europe. Walnut Creek, Left Coast Press. INST ARCH HA COL (individual chapters on various countries/areas) Colledge, S., J. Conolly, K. Dobney, K. Manning and S. Shennan (eds.) 2013. The Origins and Spread of Domestic Animals in Southwest Asia and Europe. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. (individual chapters on various countries/areas) Hadjikoumis, A., Robinson E., Viner, S. (eds.) 2011. Dynamics of neolithisation: studies in honour of Andrew Sherratt. Oxford, Oxbow. INST ARCH DA 140 GAD (individual chapters on various countries/areas) Harris, D. R. 1996. The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia: an overview. In: Harris, D. R. (ed.), The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, 552-573. ISSUE DESK IOA HAR 8 Robb, J. 2007. The early Mediterranean village: agency, material culture, and social change in Neolithic Italy. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. INST ARCH DAF 100 ROB Shennan, S., S.S. Downey, A. Timpson, K. Edinborough, S. Colledge, T. Kerig, K. Manning & M.G. Thomas 2013. Regional population collapse followed initial agriculture booms in mid-Holocene Europe. Nature Communications 4:2486. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3486. ONLINE Skoglund, P. et al. 2012. Origins and Genetic Legacy of Neolithic Farmers and Hunter-Gatherers in Europe. Science 336, 466-469. ONLINE Whittle, A. 1996. Europe in the Neolithic: the Creation of New Worlds. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, Chapters 3, 4 and 6 INST ARCH DA 140 WHI (ISSUE DESK) Whittle, A., Cummings, V. (eds.) 2007. Going over: the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition in north-west Europe. London, British Academy. INST ARCH DA 140 WHI, ISSUE DESK IOA WHI 6 (individual chapters on various countries/areas) 9. Stephen Shennan: The Neolithisation of North-Western Europe Whilst farming practices were introduced in south-eastern, Mediterranean and central Europe during the 7th and 6th mill. cal. BC, it was to be another millennium until the new economy reached the plains of northern Europe and the British Isles, with their different soils and environmental conditions. This lecture is going to look at this 'secondary' episode of neolithisation, across the North European Plain (FunnelNecked Beakers culture), Britain and Ireland. Particular attention will also been paid to the simultaneous changes in the Neolithic ‘core areas’ of central Europe and how these provided the foundations for the re14 expansion of farming across North-Western Europe. For instance, the long-standing villages which characterise the first Neolithic of central Europe give way to smaller, more ephemeral house forms. Various categories of monumental architecture also appear, including megalithic tombs. Essential reading Midgley, M. 1992. The TRB Culture: the first farmers of the north-European plains. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. Chapter 10. DA 140 MID Rowley-Conwy, P. 2011. Westward Ho! The Spread of Agriculturalism from Central Europe to the Atlantic. Current Anthropology, Vol. 52, No. S4, S431-S451. ONLINE Whitehouse, N.J. et al. 2014. Neolithic agriculture on the European western frontier: the boom and bust of early farming in Ireland. Journal of Archaeological Science 51: 181–205. ONLINE Zvelebil, M. 2007. Innovating Hunter-Gatherers. The Mesolithic in the Baltic. In: Bailey, G. Spikins, P. (eds.), Mesolithic Europe. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 18-59. INST ARCH DA 130 BAI Additional reading Bradley, R. 2007. The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2. ISSUE DESK IoA BRA 11 and INST ARCH DAA 100 BRA. Collard, M., K. Edinborough, S.J. Shennan and M.G. Thomas 2010. Radiocarbon evidence indicates that migrants introduced farming to Britain. Journal of Archaeological Science 37, 866-870. ONLINE Fairbairn, A. S. 2000. On the spread of crops across Neolithic Britain, with special reference to Southern England. In A. S. Fairbairn (ed.), Plants in Neolithic Britain and beyond. Oxford, Oxbow, 107-121. Skoglund, P. et al. 2014. Genomic Diversity and Admixture Differs for Stone-Age Scandinavian Foragers and Farmers. Science 344, 747-750. ONLINE Stevens, C.J. and D.Q. Fuller 2012. Did Neolithic farming fail? The case for a Bronze Age agricultural revolution in the British Isles. Antiquity 86: 707–722. ONLINE Whittle, A., Healey, F. and Bayliss, A. 2011. Gathering time: dating the Early Neolithic enclosures of southern Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Oxbow books. INST ARCH DAA 140 Qto WHI and ISSUE DESK IOA WHI 18 10. Stephen Shennan: Early metals and rising inequality Recent evidence demonstrates that copper metallurgy was practised in south-eastern Europe (e.g. Serbia) from the late 6th mill. cal. BC onwards. Throughout the succeeding 5th millennium cal. BC, numerous finds of copper tools, as well as old ornaments, attest to a massive demand for the new material. Changes in settlement structures (the end of tell settlements) and burial customs (appearance of large extramural graveyards) indicate shifts in social organisation and, possibly, increasing social inequality. This is accompanied by evidence for widespread exchange networks for precious goods. We will look critically at the evidence for increased social complexity and the factors cited to explain this development. Essential reading Bailey, D. W. 2000. Balkan Prehistory. London, Routledge, Chapters 5 and 6. lNST ARCH DAR BAl. lNST ARCH ISSUE DESK BAl2 Chapman, J. 1991. The creation of social arenas in the Neolithic and copper age of South-East Europe: the case of Varna. In: Garwood, P., Jennings, P. Skeates, R. Toms, J. (eds), Sacred and profane. Oxford Committee for archaeology Monograph 32. Oxford, Oxbow, 152-171. DA Qto GAR 15 Todorova, H. 1978. The Eneolithic in Bulgaria in the 5th Millenium BC. BAR International Series 49. Oxford, British Archeological Reports. Chapter 6 (see Bulgarian original for photographs of the finds). INST ARCH DARB Qto TOD Whittle, A. 1996. Europe in the Neolithic: The Creation of New Worlds. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapter 5. INST ARCH DA 140 WHI (ISSUE DESK) Additional reading Chapman, J., Higham, T., Slavchev, V., Gaydarska, B. Honch, N. 2006. The Social Context of the Emergence, Development and Abandonment of the Varna Cemetery, Bulgaria. European Journal of Archaeology 9/2-3, 159–183. ONLINE Ciuk, K. et al. (eds.) 2008. Mysteries of ancient Ukraine: the remarkable Trypilian culture 5400-2700 BC. Toronto, Royal Ontario Museum. INST ARCH DAK Qto CIU Kienlin, T. 2010. Transitions and transformations: Approaches to Eneolithic (Copper Age) and Bronze Age Metalworking and Society in Eastern Central Europe and the Carpathian Basin. BAR Int. Series 2184. Oxford, Archaeopress, Chapter 5. DA Qto KIE Radivojevic, M. et al. 2010. On the origins of extractive metallurgy: new evidence from Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science 37: 2775-2787. ONLINE 11. Stephen Shennan: The creation of supra-regional networks: Corded Ware, Bell Beakers (and Indo-Europeans?) Towards the end of the Neolithic, we observe extremely widespread distributions of sets of drinking equipment, the Globular Amphorae complex of Eastern Europe, slightly later the Corded Ware Beakers of eastern and central Europe and the Bell Beakers to the west. The very distinctive beakers were accompanied by a few dress accessories and weapon-parts, otherwise the local ceramic traditions continued more or less unchanged. Burial tended to be in single graves, often under barrows, with a gender-specific ritual. While the spread of these ‘complexes’ was formerly interpreted in the context of the creation of supra-regional networks, characterised by shared material culture, new social values and norms, recent genetic studies have reintroduced the possibility of migrations. Essential reading Allentoft, M. et al. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522: 167-172. ONLINE Cunliffe, B. (ed.) 1994. The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Chapter 7. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) Cunliffe, B. 2015. By Steppe, Desert and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Chapter 3: Horses and copper. INST ARCH DAK 15. Czebreszuk, J. 2004. Bell Beakers: an outline of present stage of research. In: Czebreszuk, J. (ed.), Similar but different. Bell beakers in Europe. Poznań: Adam Mickiewicz University, 223-224. INST ARCH DA 150 CZE Haak, W. et al. 2015. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522: 207–211. ONLINE Vandkilde, H. 2007. Culture and change in central European prehistory: 6th to 1st millennium BC. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, Chapter 5, 65-90. INST ARCH DA 100 VAN Additional reading Anthony, D. 2007. The Horse, The Wheel and Language. How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton Univ. Press. ISSUE DESK IOA ANT and online as an ebook. 16 Benz, M., van Willingen, S. 1998. Some new approaches to the Bell Beaker "phenomenon": lost paradise? Proceedings of the 2nd Meeting of the "Association Archéologie et gobelets," Feldberg (Germany), 18th-20th April 1997. BAR international series 690. Oxford, BAR. INST ARCH DA Qto BEN Fokkens, H., Nicolis, F. (eds) 2012. Background to beakers. Inquiries into regional cultural backgrounds of the Bell Beaker Complex. Leiden, Sidestone Press. INST ARCH DA 150 FOK Milisauskas, S. (ed.) 2002. European prehistory, a survey. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. Chapter 8, 247-276. INST ARCH DA 100 MIL Renfrew, A. C. 1987. Archaeology and Language. The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. Penguin. INST ARCH BD REN Sherratt, A. 1991. Sacred and profane substances: The ritual use of Narcotics in later Neolithic Europe: 403430. In: Sherratt, A. Economy and society in prehistoric Europe. Changing Perspectives. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press. INST ARCH DA 100 SHE Vander Linden, M. 2007. For equalities are plural: reassessing the social in Europe during the third millennium bc. World Archaeology 39, 177-193. IV: COMPLEX AGRARIAN SOCIETIES 12. Stephen Shennan: The beginnings of the Bronze Age The archaeological record of the Bronze Age has historically been dominated by metal. Its increasing use required extensive trade networks, especially as alloying with tin became common in the later part of the early Bronze Age. As tin is found only in a few restricted areas like Cornwall and the Ore Mountains, an interregional trade developed that entailed intense contacts. The use of the new metal was related to various economic and technical changes, and metal goods also provided another means of expressing identity, alongside ceramics and stone. Bronze artefacts are thus commonly found in burials, and hoards, and more rarely in settlements. Thanks to intensive fieldwork carried out across much of Europe over the past two decades, it is now possible to contextualise the wide range of practices linked to metal production and consumption, and to paint a more nuanced picture of the societies of the beginnings of the Bronze Age. Essential reading Harding, A. and Fokkens, H. (eds). 2013. The Oxford Handbook of European Bronze Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sherratt, A. 1994. The emergence of elites: Earlier Bronze Age Europe, 2500-1300 BC. In: B. Cunliffe (ed.), The Oxford illustrated prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 244-276. ISSUE DESK IOA CUN 6 or INST ARCH DA 100 CUN or TEACHING COLL. INST ARCH 398 Vandkilde, H. 2007. Culture and change in Central European prehistory, 6th to 1st millenium BC. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. Esp. Chapter 7 on Early Bronze Age. INST ARCH DA 100 VAN Additional reading Bradley, R. 2007. The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2. ISSUE DESK IoA BRA 11 and INST ARCH DAA 100 BRA. Harding, A. 2000. European societies in the Bronze Age. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. ISSUE DESK IOA HAR, IoA DA 150 Kristiansen, K., Larsson, Th. 2005. The rise of Bronze Age society: travels, transmissions and transformations. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapter 4 on Early Bronze Age. INST ARCH DA 150 KRI Prescott, Chr., Glørstad, H. (eds.) 2012. Becoming European? The transformation of third millennium Europe and the trajectory of second millennium BC. Oxford, Oxbow. INST ARCH DA 100 PRE 17 Roberts, B. W. 2008. The Bronze Age. In: Atkins, L., Atkins R., Leitch, V. (eds.), The Handbook of British Archaeology (revised edition). London: Constable and Robinson, 60-91. INST ARCH DAA 100 ADK Shennan, St. J. 1993. Commodities, transactions and growth in the central European Early Bronze Age. European Journal of Archaeology 1/2, 59-72. INST ARCH PERS 13. Stephen Shennan: Farmers and chieftains of Bronze Age Europe The archaeological record of the Bronze Age has traditionally been dominated by metals, and a concomitant discourse based on typology, the identification of similar stylistic features and eventually of putative large-scale networks. Thanks to new research projects and the development of commercial archaeology, a more detailed perception of the Bronze Age is now emerging. In this lecture, we will review changes in settlement pattern, funerary practices across the second and early first millennium cal. BC, as well as the rise of new practices such as hoarding. Essential reading Harding, A. and Fokkens, H. (eds). 2013. The Oxford Handbook of European Bronze Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sherratt, A. 1994. The emergence of elites: Earlier Bronze Age Europe, 2500-1300 BC. In: B. Cunliffe (ed.) The Oxford illustrated prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 244-276. ISSUE DESK IOA CUN 6 or INST ARCH DA 100 CUN or TEACHING COLL. INST ARCH 398 Sherratt, A. 1994. Reform in Barbarian Europe, 1.300-600 BC. In: B. Cunliffe (ed.) The Oxford illustrated prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 304-335. ISSUE DESK IOA CUN 6 or INST ARCH DA 100 CUN or TEACHING COLL. INST ARCH 398 Vandkilde, H. 2007. Culture and change in Central European prehistory, 6th to 1st Millenium BC. Aarhus, Aarhus University Press. Esp. Chapter 8 on Middle and Late Bronze Age. INST ARCH DA 100 VAN Additional reading Bradley, R. 1990. The passage of arms: an archaeological analysis of prehistoric hoards and votive deposits. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. INST ARCH BC 100 BRA Bradley, R. 2007. The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2. ISSUE DESK IoA BRA 11 and INST ARCH DAA 100 BRA. Fontijn, D. 2005. Giving up weapons. In: Parker Pearson, M., Thorpe, I. J. N. (eds), Warfare, violence and slavery in prehistory. Proceedings of a Prehistoric Society conference at Sheffield University. BAR international series 1374. Oxford, Archaeopress, 145-154. HJ Qto PAR Fontijn, D. 2008. Everything in its right place? On selective deposition, landscape and the construction of identity in later prehistory. In: Jones, A. (ed.), Prehistoric Europe. Oxford, Blackwell, 86-106. INST ARCH DA 100 JON Gilman, A. 1981. The development of social stratification in Bronze Age Europe. Current Anthropology 22, 122. INST. ARCH PERS and Net Harding, A. 2000. European societies in the Bronze Age. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. ISSUE DESK IOA HAR, IoA DA 150 Kristiansen, K., Larsson, Th. 2005. The rise of Bronze Age society: travels, transmissions and transformations. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. INST ARCH DA 150 KRI Pare, Ch. (ed.), Metals make the world go round: the supply and circulation of metals in Bronze Age Europe. Oxford: Oxbow. INST ARCH DA Qto PAR 18 14. Borja Legarra Herrero: The rise of states in the Mediterranean The rise in the Aegean of complex palatial structures surrounded by extensive towns and territories, and accompanied by the development of a limited literacy, has normally marked the origins of the first states in Europe. Recent research in the Iberian Peninsula has challenged this view, bringing new views on the rise of complex societies in the Mediterranean during the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC. The lecture will present the fundamental information to place and understand these processes in Iberia (3000 BC in the Guadalquivir Valley, and 2000 BC in SE Spain) and the Aegean (2000 BC on the island of Crete, and ca. 1400 BC on the Greek mainland). The lecture will explain how current debates balance ‘world-systemic’ and internal developmental approaches to explain these major changes and why they occurred across the Mediterranean significantly earlier than in temperate Europe. The collapse of the last of these palace societies around 1200 BC is a precursor to the very different Iron Age city-states of the Mediterranean world. Essential reading Broodbank, C. 2009. The Mediterranean and its hinterland. In: Cunliffe, B., Gosden, C., Joyce, R. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 677-722. INST ARCH AH CUN Chapman, R. 2005. ‘Changing social relations in the Mediterranean Copper and Bronze Ages’, in Blake and Knapp (eds.) The Archaeology of Mediterranean Prehistory, 77-101. Issue desk BLA 9; DAG 100 BLA. Gilman, A. (2013). Were There States during the Later Prehistory of Southern Iberia? In M. C. Berrocal, L. García Sanjuán & A. Gilman (Eds.), The Prehistory of Iberia. Debating Early Social Stratification and the State (pp. 10-28). New York: Routledge. INST ARCH TC 3769. INST ARCH DAP CRU. Legarra Herrero. 2016. Primary state processes on Bronze Age Crete: A social approach to change in early complex societies. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26(2). Available in Moodle. Additional reading Aranda Jiménez, G., Montón Subías, S., & Sánchez Romero, M. (2015). The Archaeology of Bronze Age Iberia. Argaric Societies. London: Routledge. INST ARCH DAP 100 ARA Bintliff, J.L. 2012. The Complete Archaeology of Greece. From hunter-gatherers to the 20th century A.D. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. DAE 100 BIN. Chapman, R. 2003. Archaeologies of Complexity. London: Routledge. INST ARCH AH CHA Cherry, J. F. 1984. The emergence of the state in the prehistoric Aegean. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 30, 18-48. Main LINGUISTICS Periodicals Cline, E. (ed.) 2010. The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. IOA CLI 2. Díaz-del-Río, P. 2010. Scaling the social context of Copper Age aggregations in Iberia. Proceedings of the XV World Congress (Lisbon, 4-9 September 2006). Oxford: Archaeopress. AH Qto INT Halstead, P. 1992. The Mycenaean palatial economy: making the most of the gaps in the evidence. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 38, 57-86. Main, LINGUISTICS Periodicals Lull, V., Micó, R., Rihuete-Herrada, C., & Risch, R. (2014). The La Bastida fortification: new light and new questions on Early Bronze Age societies in the western Mediterranean. Antiquity, 88(340), 395410. Inst Arch Pers Myers, J. W. Myers, E. E. Cadogan, G. 1992. The Aerial Atlas of Ancient Crete. DAG 14 Qto MYE; YATES Qto E 10 MYE Nocete, F., Lizcano, R., Peramo, A., & Gómez, E. (2010). Emergence, collapse and continuity of the first political system in the Guadalquivir Basin from the fourth to the second millennium BC: The long-term sequence of Úbeda (Spain). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 29(2), 219-237. Inst Arch Pers. Shelmerdine, C. (ed.) 2008. The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. IoA Issue desk SHE 16; DAG 100 SHE 19 Sherratt, A. G. 1993. What would a Bronze Age world-system look like? Relations between temperate Europe and the Mediterranean in late prehistory. Journal of European Archaeology 1/2, 1-57. Inst Arch Pers Sherratt, A. G., Sherratt, E. S. 1991. From luxuries to commodities: the nature of Mediterranean Bronze Age trading systems. In: N. Gale (ed.) Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 90. Åstrom, Jonsered, 351-386. Issue Desk DAG Qto STU 90 Whitelaw, T. 2001. From sites to communities: defining the human dimensions of Minoan urbanism. In: Branigan, K. (ed.) Urbanism in the Aegean Bronze Age. Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology 4, Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 15-37. Issue Desk BRA; DAE 100 BRA 15. Marc Vander Linden: The Iron Age north of the Alps The Iron Age is characterised, in continental Europe, by increased movement of goods, techniques and ideas, manifested by the development of supra-regional trends. As part of this session, we will review changes in funerary practices, which remain a privileged source of information on social structure, and especially the evidence for settlement. During the Early Iron Age, fortified settlements are linked to rich chariot burials, often associated with imports from the Mediterranean world. The settlement pattern changes dramatically during the Later Iron Age, wit the development of dedicated sanctuaries, a dense network of farmsteads and, during the last two centuries BC, the creation of extensive settlement, the socalled oppida (Latin for towns). Essential reading Collis, J. 1992 (reprinted from 1984). The European Iron Age. London, Batsford. Chapters 3 and 4. INST ARCH DA 160 COL (ISSUE DESK) Cunliffe, B. 1994. Iron Age Societies in Western Europe and beyond, 800-140 BC. In: Cunliffe, B. (ed.) The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 336-372. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) Cunliffe, B. 2008. Europe between the oceans: themes and variations, 9000 BC-AD 1000. New Haven, Yale University Press. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN Chapters 8+9. Additional reading Bradley, R. 2007. The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Chapter 2. ISSUE DESK IoA BRA 11 and INST ARCH DAA 100 BRA. Collis, J. 2003. The Celts: origins, myths & inventions. Stroud, Tempus. INST ARCH DA 161 COL Dietler, M. 1994. "Our Ancestors the Gauls": Archaeology, Ethnic Nationalism, and the Manipulation of Celtic Identity in Modern Europe. American Anthropologist NS 96/3, 584-605. NET Fernández-Götz, M., Krausse, D. 2012. Heuneburg, first city North of the Alps. Current Archaeology 55, 2834. ONLINE Kern, A. 2009. Kingdom of salt: 7000 years of Hallstatt. Veröffentlichung der Prähistorischen Abteilung 3. Vienna, Natural History Museum. INST ARCH DABB KER Moscati, S. (ed.) 1991. The Celts. London, Thames and Hudson. INST ARCH CELTIC QUARTOS AI0 MOS (ISSUE DESK) Thurston, T. 2009. Unity and diversity in the European Iron Age: out of th mists, some clarity? Journal of Archaeological Research 17 (4): 347-423. Wells, P. 2001. Beyond Celts, Germans and Scythians: archaeology and identity in Iron Age Europe. London, Duckworth. INST ARCH DA 160 WEL 16. Marc Vander Linden: The Iron Age in the British Isles After a drop in the circulation and deposition of bronze artefacts at the beginning of the 1 st mil. Cal. BC, iron becomes gradually more important. This new technological preference is accompanied by changes in funerary practices and, especially in settlement pattern, with the multiplication of roundhouses, enclosed 20 settlements, hillforts (during the period between 600 and 400 cal. BC), and, towards the end of the sequence, the construction and use of 'oppida' reminiscent of extent contemporary continental sites. Links with the continent, and the Roman Empire during the last century BC and first century AD are well attested. Essential reading Collis, J. 1992 (reprinted from 1984). The European Iron Age. London, Batsford. Chapters 3 and 4. INST ARCH DA 160 COL (ISSUE DESK) Cunliffe, B. 1994. Iron Age Societies in Western Europe and beyond, 800-140 BC. In: Cunliffe, B. (ed.) The Oxford Illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 336-372. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK) Cunliffe, B. 2008. Europe between the oceans: themes and variations, 9000 BC-AD 1000. New Haven, Yale University Press. INST ARCH DA 100 CUN Chapters 8+9. Additional reading Collis, J. 2003. The Celts: origins, myths & inventions. Stroud, Tempus. INST ARCH DA 161 COL Haselgrove, C. & Moore, T. (eds). The later Iron Age in Britain and beyond. Oxford: Oxbow Books. INST ARCH DAA 160 Qto HAS Haselgrove, C. & Pope, R. (eds) 2007. The earlier Iron Age in Britain and the near continent. Oxford: Oxbow Books. INST ARCH DAA 160 Qto HAS Thurston, T. 2009. Unity and diversity in the European Iron Age: out of th mists, some clarity? Journal of Archaeological Research 17 (4): 347-423. Wells, P. 2001. Beyond Celts, Germans and Scythians: archaeology and identity in Iron Age Europe. London, Duckworth. INST ARCH DA 160 WEL 17. Ulrike Sommer: Nomads of the Steppe Zone from the early Bronze Age to the Scythians During the early Bronze Age, true nomadism developed in the steppe zone of Eastern Europe and Asia. Horse-drawn wagons were used as mobile homes, und sumptious burials in large barrows (urgans) marked the land. The steppe-zone provided a large contact zone throughout history, connecting China, Persia and the cultures around the Black Sea, at times extending as far west as the Carpathian Basin. We will look at the development of this nomadic way of life and the interaction with settled communities. In the Iron Age, the Scythians came into contact with Greek settlers around the Black Sea, which left a deep mark on their material culture. Essential reading Dolukhanov, P. M. 2002. Alternative Revolutions: hunter-gatherers, farmers and stock-breeders in the Northwestern Pontic area. In: Boyle, K. Renfrew, C. Levine, M. Ancient interactions: East and West in Eurasia. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 13-24. INST ARCH DBK BOY Frachetti, M. D. 2008. Pastoralist landscapes and social interaction in Bronze Age Eurasia. Berkeley, University of California Press. Chapter 2, An Archaeology of Bronze Age Eurasia, 31-72. INST ARCH DBK FRA Rolle, R. 1989. The Scythians. London, Batsford. INST ARCH DAK 160 ROL Very traditional, but still a good English-language overview. Additional reading Alekseev, A. 2000. The Golden Deer of Eurasia: Scythian and Sarmatian treasures from the Russian steppes-The Hermitage, Saint Petersburg and the Archaeological Museum Ufa. New Haven: Yale University Press. INST ARCH DAK 15 Qto ARU 21 Chernych, E. N. 2008. Formation of The Eurasian “Steppe Belt” of stockbreeding Cultures: Viewed through the Prism of Archaeometallurgy and Radiocarbon Dating. Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 35/3, 36–53. INST ARCH PERS *Dolukhanov, P. M. 1996. The early Slavs: Eastern Europe from the initial settlement to the Kievan Rus. London, Longman. Chapters 5 and 6. INST ARCH DA 100 DOL Kohl, Ph. 2007. Making of Bronze Age Eurasia. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. INST ARCH DBK KOH and Online excellent as a reference work Piotrovsky, B. 1987. Scythian Art. Oxford, Phaidon. Reeder, E. D. 1999. Scythian Gold: Treasures from Ancient Ukraine. New York, Harry N. Abrams. SSEES U.XX.3 SCY Shishlina, N. I. 2008. Reconstruction of the Bronze Age of the Caspian Steppes: life styles and life ways of pastoral nomads. BAR International Series 1876. Oxford, Archaeopress. INST ARCH DBK Qto SHI See also Aruz, J. Farkas, A. Fino, E. V. (eds) 2007.The golden deer of Eurasia: perspectives on the Steppe Nomads of the ancient world. New Haven, Yale University Press. INST ARCH DAK 15 ARU Braund, D. (ed.), 2005. Scythians and Greeks: cultural interaction in Scythia, Athens and the early Roman Empire (sixth century BC to first century AD). Exeter, University of Exeter Press. INST ARCH DAK 15 BRA Kadrow, Sl. et al. (eds) 1994. Nomadism and pastoralism in the circle of Baltic-Pontic early agrarian cultures, 50001650 BC. Baltic-Pontic studies 2. Poznań: Institute of Prehistory, Adam Mickiewicz University. INST ARCH DAK 15 KAD 18. Corinna Riva: Greeks, Phoenicians and others across the Mediterranean During the first millennium BC mobility increased throughout the Mediterranean and urban life developed. By the 6th century BC at latest Greeks, Phoenicians, Etruscans and others had established cities around the Mediterranean coast and in the hinterland. These states were very different from the MinoanMycenaean palace states. They developed new urban settlements and a type of political organisation that was new in Europe, if well known in the Near East, the city state. By the mid-first millennium BC, many of them developed formal legal systems, adopted alphabetical writing and coinage and engaged in stateorganised military operations and construction projects. A class system emerged, with aristocrats at the top and slaves at the bottom. Both the Greek and the Phoenician city states founded colonies and traded with the European hinterland. We are going to look how goods and ideas may have been transferred and manipulated during these contacts, and how this influenced the development in Continental Europe. Essential reading Cunliffe, B. W., Osborne, R. (eds) 2005. Mediterranean Urbanization 800-600 BC. Oxford, Oxford University Press. IoA: DAG 100 OSB & Issue Desk; Main: HUMANITIES Pers (the whole book is relevant, but see, in particular, chapter by Osborne, van Dommelen, Rasmussen, de Polignac). Morris, I. 2013. ‘Greek multi-city states’, in P. Bang and W. Scheidel (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the State in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, 279–303. Main: ANCIENT HISTORY A 60 BAN Morris, I. 1997. ‘An archaeology of inequalities? The Greek city-states’, in D. L. Nichols and T. H. Charlton (eds), The Archaeology of City-States: Cross-Cultural Approaches. INST ARCH Issue desk NIC 2; BD NIC. Bradley G. 2000. ‘Tribes, states and cities in central Italy’, in E. Herring and K. Lomas (eds.) The Emergence of State identities in Italy, 109-129. 22 Additional reading Morgan, C. 2003 Early Greek states beyond the polis. London, Routledge (Main: ANCIENT HISTORY P 55 MOR) on Greek non-polis states Ian Morris 1987 Burial and Ancient Society: The Rise of the Greek City-State. Cambridge, CUP (ISSUE DESK IOA MOR 5) Moscati, S. (ed), 2001. The Phoenicians. London, I. B. Taurus. INST ARCH DAG 100 MOS Murray, O., and S. Price, (eds.) 1990. The Greek City From Homer to Alexander Main: ANCIENT HISTORY P 61 MUR (the article by Runciman is a provocative classic). Niemeyer, H. G. 2000. The early Phoenician city-states on the Mediterranean. Archaeological elements for their description. In: Hansen, M. (ed.), A comparative study of thirty city-state cultures. An investigation conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre. Kobenhavn: Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, 89-115. INST ARCH BC 100 Qto HAN and ANCIENT HISTORY (Main) QUARTOS A 72 HAN Nijboer A.J. 2004. ‘Characteristics of emerging towns in Central Italy, 900/800 to 400 BC’, in P. Attema (ed.) Centralization, early Urbanization and Colonization in first millennium BC Italy and Greece, Part 1, 137-156 [IoA: Issue Desk] Osborne, R. 1987. Classical Landscape With Figures: The Ancient Greek City and Its Countryside, Chapter 1 ‘The paradox of the Greek city’. Tsetskhladze, G. 2006. Greek colonisation: an account of Greek colonies and other settlements overseas. Leiden, Brill. ANCIENT HISTORY P 61 TSE 19. Kris Lockyear: The impact of Rome on European societies From the early 2nd century BC Rome, having established control over most of Italy and the Mediterranean, turned its attention to lands north of the Alps. Over the next two centuries it extended its empire over much of Europe, stopping at major frontiers along the Rhine and Danube, and in northern Britain. Within the frontiers Roman structures and institutions were established: military camps and fortifications were followed by towns of Mediterranean type; Latin became the official language; Roman law prevailed; and material culture came under a wide range of imperial influences. Beyond the frontiers too, the impact of contact with Rome was considerable, fed by Rome's need for supplies of raw materials and labour. In return for these, the local elites obtained Mediterranean manufactured goods, some of which, especially those connected with wine consumption, became significant status symbols, used to enhance and reinforce increasing social stratification. However, these processes did not simply involve the imposition of cultural templates derived from Rome on European societies, but rather a wide range of local interactions that produced multiple different kinds of Roman identities. Essential reading Cunliffe, B. 1994. The impact of Rome on barbarian society. In: Cunliffe, B. (ed.), The Oxford illustrated Prehistory of Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 411-446 (Chapter 2). INST ARCH DA 100 CUN (ISSUE DESK). James, S. 2001. ‘Romanization’ and the peoples of Britain. In: S. Keay, Terrenato, N. (eds.) Italy and the West: comparative issues in Romanization. Oxford, Oxbow Books, 77-89. DA 170 KEA; Teaching Collection 3303. Woolf, G. D. 1992. The unity and diversity of Romanization. Journal of Roman Archaeology 5, 349-352. INST ARCH Pers Additional reading Ferris, I. M. 2000. Enemies of Rome: Barbarians through Roman eyes. Stroud: Sutton. A HIST R 72 FER Hingley, R. 2005. Globalizing Roman culture: unity, diversity and empire. London, Routledge. A HIST R 72 HIN Wells, P. 1999. The barbarians speak: how the conquered peoples shaped Roman Europe. Princeton, Princeton University Press. A HIST R 20 WEL 23 Wells, P. 2001. Beyond Celts, Germans and Scythians: archaeology and identity in Iron Age Europe. London, Duckworth. INST ARCH DA 160 WEL Woolf, G. 1998. Becoming Roman: the origins of provincial civilization in Gaul. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. A HIST R 28 WOO 20. Ulrike Sommer, Stephen Shennan: Practical, handling session Arrangements: You will be divided into small groups in order to study and handle a range of artefacts relating to later European prehistory. Bring your notes and handouts! 4 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Libraries and other resources In addition to the Library of the Institute of Archaeology, other libraries in UCL with holdings of particular relevance to this degree are: British Museum, British Library Information for intercollegiate and interdepartmental students Students enrolled in Departments outside the Institute should obtain the Institute’s coursework guidelines from Judy Medrington (email j.medrington@ucl.ac.uk), which will also be available on the IoA website. IMPORTANT INSTITUTE OF ARCHAELOGY COURSEWORK PROCEDURES General policies and procedures concerning courses and coursework, including submission procedures, assessment criteria, and general resources, are available in your Degree Handbook and on the following website: http://wiki.ucl.ac.uk/display/archadmin. It is essential that you read and comply with these. Note that some of the policies and procedures will be different depending on your status (e.g. undergraduate, postgraduate taught, affiliate, graduate diploma, intercollegiate, interdepartmental). If in doubt, please consult your course co-ordinator. GRANTING OF EXTENSIONS: . New UCL-wide regulations with regard to the granting of extensions for coursework have been introduced with effect from the 2015-16 session. Full details are available here: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/srs/academic-manual/c4/extenuating-circumstances/. Note that Course Coordinators are no longer permitted to grant extensions. All requests for extensions must be submitted on a new UCL form, together with supporting documentation, via Judy Medrington’s office and will then be referred on for consideration. Please be aware that the grounds that are now acceptable are limited. Those with long-term difficulties should contact UCL Student Disability Services to make special arrangements. ***************************** 24