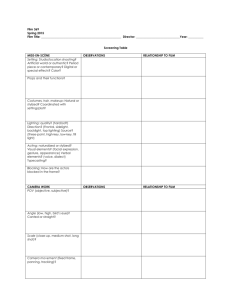

Some Useful Terms and Ideas for Formal Analysis of Films sound MISE-EN-SCÈNE

advertisement

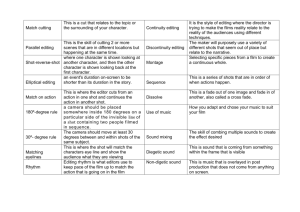

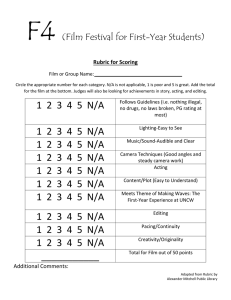

Some Useful Terms and Ideas for Formal Analysis of Films The key formal elements of film are mise-en-scène, cinematography (camerawork and editing) and sound, as well as narrative organisation. MISE-EN-SCÈNE Corrigan and White, The Film Experience (2004 edition): p.42 ‘[M]ise-en-scène refers to those elements of a movie which are put in place before the film actually begins and are employed in certain ways once the filming does begin. The mise-en-scène contains the scenic elements of a movie, including actors, lighting, sets and settings, costumes, makeup, and other features of the image that exist independent of the camera and the processes of filming and editing.’ ‘None of the elements of mise-en-scène – from props to acting to lighting – can be assigned standard meanings because they are always subject to how individual films use them. They have also carried different historical and cultural connotations at different times.’ pp.44-6 Sets and settings – constructed (including CGI) or location; scenic realism, scenic atmosphere and connotations. pp.51-2 Props – instrumental, metaphorical, cultural and contextualised pp.52-6 Actions and speech, performance and blocking – voice, bodily movement, naturalistic or stylised acting, leading and supporting actors, stars and character actors, relationship with the rest of mise-en-scène including performative development, social and graphic blocking p.57 Costumes and makeup – character highlights and narrative markers p.58-60 Lighting Some useful terms: natural and naturalistic lighting; dramatic lighting, directional lighting, key lighting and highlighting; backlighting, frontal lighting, sidelighting, underlighting and top lighting; hard and soft lighting and shading; high-key and low-key lighting and chiaroscuro. See Bordwell and Thompson, Film Art (2008 edition), pp. 124-131 pp.67-69 Naturalistic (historical or everyday) v. theatrical (expressive or constructive) mise-en-scène CINEMATOGRAPHY This involves everything to do with how what is in front of the camera is captured, organised and reproduced by the camera, including: Camerawork • choice of film stock (e.g. 35mm) or digital recording, as well as how the look of this might be altered by certain special effects such as grading (altering colours by using filters in filming or with post-production effects). • framing Shape: aspect ratio; masks and irises (Bordwell and Thompson pp.182-187) What is in the frame? Crowded/ empty? • distance from main subject(s) Extreme long shot, long shot, medium long shot, medium shot, medium close-up, close-up and extreme close-up (Bordwell and Thompson p.191) • position and angle Angle (straight-on, high or low), level (level or canted) and height of camera (Bordwell and Thompson p.190) • focus and depth Wide-angle, normal and telephoto lens; zooms; rack focusing; deep and selective (often shallow) focus; other special effects. (Bordwell and Thompson pp. 168-178) • on and off screen space (see Bordwell and Thompson pp.187-9) • camera movements Pans, tilts, tracks (or dollies) and cranes; static camera; (steadicam); hand-held camera. • duration of shot (long and short takes etc. NB NOT the same as ‘long/short shot’, a spatial measure) Especially compared to conventions of time and above all in the rest of the film. Sometimes aspects of the film are hard to separate out into cinematography versus mise-en-scène. For instance the composition and balance of objects and patterns in the frame is related to what is chosen to be framed in the first place. Early ‘special effects’ such as rear projections and constructed sets in general were seen as aspects of mise-en-scène but what about CGI (computer-generated imagery), which can be the entire frame? The colours in a shot can be altered using filters in front of the camera, technically an aspect of mise-en-scène, rather than grading in post-production; yet for your purposes it makes little difference and there is no real need to know how the effect was created. These terms only need to be used when they prove useful! Here are some elements to think about for analysing shots that combine aspects of both categories: • relationship of camera movements to movements of the performers • role of camera movements in maintaining or changing the centre of interest • balance and perspective Where is the action in the frame e.g. off-centre or centred? • composition: pattern and tones Palette of colours, graphic detail and patternings, including blocking of figures. For analysing not just shots but sequences – groups of shots typically unified by a theme and/or plot development and/or setting, these details need to be combined with consideration of the techniques of: Editing This refers to how shots are organised in relation to each other: it determines shot lengths and what is plaed next to what, a key element of storytelling. Some useful terms for different types of transition between shots beyond the straight cut include fades, dissolves and wipes See also Dimensions of Editing, Bordwell and Thompson, pp.220-231 on: Graphic relations - graphic matches or discontinuity? Rhythmic relations - tempo Spatial relations – establishing and re-establishing shots, the Kuleshov effect Temporal relations between shots – flashbacks and elliptical editing (use of overlapping editing and empty frame) N.B. Other elliptical possibilities including flash-forwards and cutaways It is important to be aware of: The Continuity Style (Bordwell and Thompson, pp. 231-251) of editing, the most basic form of storytelling established by classical cinemas (1930-50s/60s) and familiar to all of us as the basic grammar of most contemporary mainstream filmmaking. Features: (re-) establishing shots, shot/ reverse-shot pattern, eyeline and action matches, spatial continuity and the 180 degree system N.B. also 30 degree rule (see Bordwell and Thompson p.254) C&W, pp. 147-9: Continuity editing is not inevitable or ‘correct’; rather it creates shot patterns that: Shape space and time to approximate a closed fictional world Construct a logic and rhythm that mime human perception ‘It is something of an irony that emulating human perspective entails departing from it – most notably to show the person who is looking. [...] Film theorists speculate that such spatial practices hide a source of potential anxiety for the viewer.[...] Our human perception actually proceeds from what Dziga Vertov and his associates call the “camera eye”, a fact we are supposed to forget. In a subjective shot from a horror film that is not anchored by a reverse shot, we are forced to wonder whose point of view the camera is assuming.’ N.B Term ‘suture’ – literally referring to stitching up a wound - is sometimes used to refer to our sense of being inserted in a specific place in a film, a place from which to look at its fictional world. For a particular, more detailed attempt to elaborate an entire ‘grammar’ of film editing, see Christian Metz’s theories (based on the work of linguistician Ferdinand de Saussure), also summarised in James Monaco, How to Read a Film (OUP, 1981 edition), pp.244-7. Within a broadly continuous editing style, be aware of: - Crosscutting (or parallel editing) pp.244-5 Bordwell and Thompson ‘primarily a means of presenting narrative actions that are occurring in several locales at roughly the same time’ ‘binds the action together by creating a sense of cause and effect and temporal simultaneity’ ‘builds up suspense, as we form expectations that are only gradually clarified and fulfilled’ Some other terms you might come across: Intensified Continuity - pp.246-9 Bordwell and Thompson David Bordwell has argued that in mnainstream Hollywood today a kind of intensified version of the continuity style is the norm. This is broadly characterised by faster editing (shorter average shot lengths [ASLs]) and more extreme focal lengths (more long shots and extreme close-ups, less ‘scene-setting’ medium and medium long shots, with an occasionally disorienting effect e.g. in action films) N.B. Influence of television Montage Most basically, another word for editing – the French term for the same process. Secondarily, within the continuity style, it has come to refer to a kind of rapid sequence used for descriptive purposes and/ or to show the passage of time (montage sequence). As Monaco notes (p.239) it is not insignificant that the French conception stresses the process of creating something new (monter = to put up e.g. a structure, building etc.), whereas editing implies cutting back. European montage is meant in this sense of the term, after the German Expressionists and Eisenstein seized on this meaning, stressing the construction of a film. N.B. This meaning is also linked to the previous one as in both cases it signifies a style that emphasises the breaks and contrasts between images joined by a cut. It is here contrasted with découpage classique or the ‘invisible’ continuity style and associated with.... Disjunctive (or ‘Visible’) Editing Distanciation techniques/ alienation effects and the influence of Bertolt Brecht. In film, the jump cut - ‘a disjunctive cut that interrupts a particular action and, intentionally or unintentionally, creates discontinuities in the spatial or temporal development of shots’. C&W p.151 ‘where the natural movement is interrupted’ Monaco p.240 ‘when two shots of the same subject are cut together but are not sufficiently different in camera distance or angle , there will be a noticeable jump on screen’ B&T p.254 It is useful to distinguish the continuity and disjunctive editing traditions in order to analyse them but in fact, in modern filmmaking, it is quite possible to find these two traditions converging in the style of a single film – see C&W p.147 Cf. ‘As the two formal traditions of continuity and disjunctive editing converge, the values associated with each tradition become less distinct. For Eisenstein, calling attention to the editing was important because it could change the viewer’s consciousness. For contemporary filmmakers, disjunctive editing may serve more as an innovative “look”.’ E.g. Oliver Stone, closely associated with both Hollywood filmmaking and disjunctive editing. N.B. Also influence of music video aesthetics e.g. David Fincher, director of SeFen and Fight Club, C&W, p.157. N.B. Also the nondiegetic insert (see definition of ‘diegesis’ later in this document) – roughly, a cutaway to an image that is clearly not part of the story e.g. suddenly cutting to a cartoon image of the main character in a live action film for artistic effect (B&T p.254-5) SOUND Corrigan and White p. 201 In general, as a set of indicators of a real, multidimensional world, film sounds bring the viewer/ auditor the impression of being authentically present in space. And, as a less ‘literal’ sign than the image and a more immediately perceived experience than the visual, sound encourages the viewer to experience emotion. pp. 169-70 - synchronous (visible onscreen source) v. asynchronous sound (also known as onscreen v. off-screen sound) parallelism (when sound and image ‘say the same thing’) v. counterpoint/ contrapuntal sound Diegetic v. nondiegetic sound (see definition of ‘diegesis’ later in this document). Can the characters hear the sound? If not, it is likely to be nondiegetic e.g. musical score. p.171 -2 N.B. Important influence of melodrama (= music plus drama) on cinematic conventions, as well as music-hall and vaudeville. pp.175-80 Some technical terms: direct and reflected sound, postproduction sound and sound editing, looping, sound bridges, postsynchronous sound and automated dialogue replacement (ADR). ‘Although we might not think about it when we are watching a movie, the presence of the image always implies the absence of the object. Listening to cinema sound affords a somewhat different experience. The reproduction of sound is undoubtedly a copy. But it seems to have the same effect on the ear as the original sound, even if its source, direction, tonality or depth has changed. We believe we are hearing the sound right here, right now’. Cf. Importance of playback equipment: three channels in cinema standardised since Apocalypse Now (1979) cf. improvement in stereo recording from Dolby. pp. 184-90 The voice in film: Sound perspective; use of overlapping dialogue Various functions of voice-off and voiceoever pp.190-5 Music in film Narrative music: background music and motives p.196 on sound effects NARRATIVE AND ITS ORGANISATION ‘Stories give people the feeling that there is meaning, that there is ultimately an order lurking behind the incredible confusion of appearances and phenomena that surrounds them...[Yet] for me I totally reject stories, because for me they only bring out lies...and the biggest lie is that they show coherence where there is none...Stories are impossible, but it’s impossible to live without them.’ Wim Wenders, quoted in Corrigan and White, p.214 In Bordwell and Thompson’s glossary, they give the following definitions: Plot: In a narrative film, all the events that are directly presented to us, including their causal relations, chronological order, duration, frequency and spatial locations. Opposed to... Story: ...which is the viewer’s imaginary construction of all the events in the narrative. Narration: The process through which the plot conveys or withholds story information. The narration can be more or less restricted to character knowledge and more or less deep in presenting characters’ mental perceptions and thoughts. Diegesis is literally ‘the telling of a story by a narrator’. N.B The narrative includes nondiegetic – or non-story – information (Corrigan and White p.233) Some of the principles of narrative: Causality Character motivation – see also Corrigan and White pp.225-231 on character coherence and depth; character grouping (protagonists, antagonists, minor or secondary characters, social hierarchies and collective characterisations); character types (figurative, archetypal or stereotyped); and character development (external and internal change, progressive and regressive development) Withholding of information – see also Corrigan and White p.233 on plot selection and omission Temporality – duration and frequency (N.B. recent popularity of puzzle films); see also Corrigan and White pp.234-7 on temporal schemes including linear chronology, parallel plots, deadline structures, flashbacks and flash-forwards and other types of plot ordering. Space – often plot and story here coincide but off-screen spaces can be important to a story (e.g. for backstory); see also C&W p.238 on ideological locations, psychological locations and symbolic spaces Plot structure: openings (in medias res, exposition, setups), endings (open or conclusive?) and patterns of development... ‘The plot may arrange cues in ways that withhold information for the sake of curiosity and surprise. Or the plot may supply information in such a way as to create expectations or increase suspense. All these processes constitute narration, the plot’s way of distributing story information in order to achieve specific effects. Narration is the moment-by-moment process that guides us in building the story out of the plot.’ Bordwell and Thompson, p.88. Range and depth of story information – linked to narrative point of view (first or third person, narrators omniscient or otherwise); see also C&W pp.240-46 on voiceovers and narrative frames, reflexive narration, unreliable narration, multiple narrations and anthology or compilation films. C&W pp. 248-1 classical narratives (usually seen as 1930s and ‘40s though some give longer dates): are centred on one or more central characters who propel the plot with a cause-and-effect logic (whereby an action generates a reaction) develop plots with linear chronologies directed at certain goals (even when flashbacks are integrated into that linearity) employ an omniscient or a restricted narration that suggests some degree of realism classical Hollywood narratives – significant focus on individual drama and psychology v. European classical narratives – story more often set in large and varied social contexts e.g La Règle du jeu (Renoir, 1939) and postclassical Hollywood narratives - post WWII - strained but maintained the classical formula for coherent character and plots e.g. Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976) N.B. Also alternative film narratives including new-wave (not just in France) and other art cinema narratives and non-Western narratives of various kinds.