Fire 5

advertisement

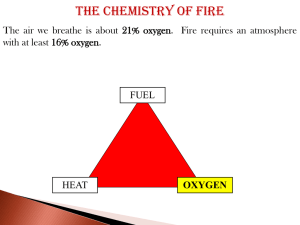

5 Fire The basic role of an investigator at fire scene is twofold: to determine the origin of the fire (the site where the fire began) to examine closely the site of origin to try and determine what it was that caused a fire to start at or around that location. An examination would typically begin by trying to gain an overall impression of the site and the fire damage; this could be done at ground level or from an elevated position. From this one might proceed to an examination of the materials present, the fuel load, and the state of the debris at various places. The search for the fire's origin should be based on elementary rules such as:∙ fire tends to burn upwards and outwards (look for V‐patterns along walls) the presence of combustible materials will increase the intensity and extent of the fire; the fire will rise faster as it gets hotter (look for different temperature conditions) the fire needs fuel and oxygen to continue a fire's spread will be influenced by factors such as air currents, walls and stairways; falling burning debris and the effect of fire‐fighters will also have an influence a knowledge of the colour and state of various materials at elevated temperatures is required to help determine the temperature of the fire in different locations An examination is also carried out of structural deformations, char depths, smoke patterns. It is important to try and discover if the fire started at floor level, as from a cigarette butt, or at elevated level, as for a gas explosion. This summary attempts only to indicate some of the steps typically undertaken. These procedures are designed to locate the site of origin (or seat) of the fire. Multiple sites of origin suggest a deliberately lit fire. Assuming that the site of origin has been found a thorough examination of the debris in this area is then necessary. All electrical appliances in the vicinity should be examined. The presence of any flammable liquids, trails, or spalling of concrete or intense burn‐ marks in the floor should be checked. No fire can commence without an ignition source. One should therefore be on the lookout for matches, lighters, sources of sparks, hot objects, chemicals, gas and electrical lines, cigarettes, fireplaces and chimneys. Arson If a fire is not the result of an accident, it must have been deliberately‐lit; arson. The motives to commit arson include vandalism, fraud, revenge, sabotage and pyromania. A major objective in any suspected case of arson would be to search for, locate, sample and analyse residual accelerants. Most, though certainly not all incendiary fires involve the use of an accelerant to speed the ignition and rate of spread of fire. A rapid and intense fire, inconsistent with the natural fuel loading is indicative of an accelerated fire. Such a fire is likely to be initiated at ground level, possibly in a number of sites and may produce trail marks, burn‐throughs or spalling of concrete. The accelerants most‐commonly used, on account of their flammability and ready availability are petrol, kerosene, mineral turpentine and diesel. Other accelerants such as alcohols, acetone and industrial solvents are less commonly used. It might be thought (certainly many arsonists assume) that after an intense fire there will be negligible amounts of such accelerants remaining. Given our current sophistication of analytical techniques, this is not true. The amount of accelerant remaining after a fire will depend on factors such as the quantity and type of compound used, but also on the nature of material it is poured on, the elapsed time since the fire, and the severity of the fire. Chemists have been able to locate and detect trace amounts of liquid hydrocarbons in soil beneath a gutted house several months after a fire. 5. Fire Detection of trace quantities of materials requires careful attention to sampling techniques and analysis. The most frequently sampled material is flooring material such as wood, carpet, soil and linoleum. Porous material is best. There is a need to take control samples in some cases, away from the area where the accelerant is suspected, but preferably of the same material as the sample. Some investigators use "sniffers" at fire scenes. These portable detectors usually note changes in oxygen level on a semiconductor. They are not specific for liquid hydrocarbons, responding to a variety of vapours, and need to be used with caution. They can be used as a guide as to the best place from which to collect samples, for removal to, and analysis in, the chemical laboratory. Sampling The materials found to give the most positive analyses for accelerants are porous samples; carpet and underlay, cardboard, paper, felt, cloth and soil. At all stages, because of the sensitivity of the analysis, care must be taken to avoid contamination. In our experience unlined metal cans have been found to be the best containers. Lined cans may have a coating which contains volatile components and should not be used. Plastic bags may allow diffusion of volatile components either into or out of the sample and are not recommended. Glass containers may be used, but the cleanliness of lids needs to be assured. Cans need to be clean and well sealed, and clearly labelled, for transport to the laboratory. At the laboratory they need to be documented and kept secure prior to analysis. Analysis Gas chromatography is the preferred technique in the analysis of fire residues when attempting to identify accelerants. If the conditions are carefully controlled, it becomes relatively easy to identify pure petroleum fractions since they are normally composed of a large number of identifiable components. Introduction To Forensic Science IS5.2