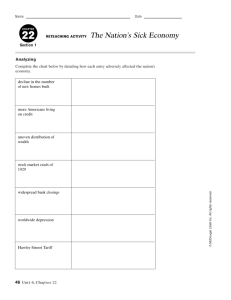

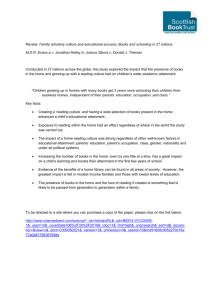

W O R K I N G Childhood Educational

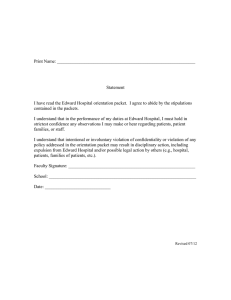

advertisement