1 Europe’s engagement with the wider world from the end of... eighteenth century, to transform her industrial and consumer cultures. ...

advertisement

1

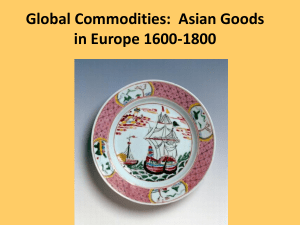

Global Commodities: Asian Goods in Europe 1600-1800

Lecture to the Enlightenment course

Europe’s engagement with the wider world from the end of the fifteenth century was, by the

eighteenth century, to transform her industrial and consumer cultures. The lecture will focus on the

trade in manufactured products: how they were made, marketed and distributed between Asia and

Europe.

Setting the Scene

The Santiago and the Santa Catarina

In 1602 the Dutch seized two Portuguese ships, the Santiago and the Santa Catarina. The Santa

Catarina alone contained 10,000 pieces of porcelain; their sale over the next two years in

Amsterdam drew traders from all over Europe. The ship also contained ‘pintadoes’, the painted and

printed cotton calicoes that were later in the century to be marketed as the new textile for Europe’s

fashionable clothing.

Joseph Priestley’s inventory

Nearly two centuries later, in 1791, not far from Birmingham the scientist, dissenting minister and

radical advocate of the French Revolution, Joseph Priestley rushed from his house pursued by a mob.

The mob ransacked and torched his house. The inventory for damages that was later submitted

listed colossal amounts of chinaware, including a dinner set of Nankeen ware of 108 pieces and a

Nankeen tea set, named for the export ware porcelain imported from China. There were 3 sets of

Wedgwood ware, and other tea and coffee sets as well as punch bowls, tea and coffee pots,

chocolate cups, sugar and custard cups and dessert plates.

Key questions: Why did Europeans increase their demand for quality and luxury goods in the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries?

What impact did encounters with wider-world cultures and commodities play in this?

Just how did Europe’s pursuit of quality goods turn a pre-modern encounter with precious cargoes

into a modern globally-organized trade in colonial groceries and Asian export ware?

How in turn did this affect the design, product development and industrial development of

Europeans’ own manufactures?

1. My research

I have made an effort to move out from more conventional studies of trade or East India companies

to analyse the exchange of material culture and the transmission of knowledge, including that of

skills, design and materials. I want to bring together the study of trade, of consumption and of

production.

My agenda involves engaging with objects – taking an approach through material culture, and it

involves a global approach.

2

Publications: Maxine Berg, ‘In Pursuit of Luxury: Global History and British Consumer Goods in the

Eighteenth Century.’ Past and Present, 182 (2004), pp. 85-142; Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in

Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford, 2005); Maxine Berg ed., Writing the History of the Global:

Challenges for the 21st Century (2013); Maxine Berg ed., Goods from the East: Trading Eurasia 16001800 (2015).

2. Material Culture

I draw first on the study of Material Culture.

See: Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello, Writing Material Culture History (2015)

Artefacts are tools for creating global connections. This requires historians to use Interdisciplinary

approaches: economic and social history, archaeology, art history, anthropology, and literary

analysis.

Objects add to the study of textual sources.

objects we look at express exchange and design on a global scale; they tell us about taste

and about power relations over great distances.

Limitations of material culture history

An object we look at in museums have had many different lives – looking at it does not tell

us who made it, who owned and used it, and how this changed over time.

Interpretations of an object show many problems:

Interpretations of objects:

Riello and Adamson recount interpretations of a Japanese suit of armour in the Tower of

London in their chapter in Writing the History of the Global (ed. Berg, 2013).

This Japanese suit of armour in the Tower of London dated to 1613, and sent as a

diplomatic gift to James I by the Emperor Ieyasu.

-There are similar suits of armour in various European courts, but these were described

in the years up to the end of the 19th Century as given by the Emperor of the Mougal, or

as the armour of Montezuma or that of the Moor of Grenada.

Global History is another relatively recent approach and methodology. It brings us new

questions and methods to address the goods that passed between Asia and Europe.

Global history is not just about adding wider areas of the world to what we study on

Europe.

Neither is global history about reasserting the place of the grand narratives discounted

in postmodernist critiques.

What global history offers is a different perspective, a different point of view.

3

3. Trade with Asia

Many historians in the past have discounted the significance of these goods because they were

luxury goods or they were just for the elites.

Adam Smith knew their significance:

He wrote: ‘The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good

Hope are the two greatest and most important events in the history of mankind.’

How big was this trade? Jan de Vries has estimated that for Europeans as a whole they consumed c.

1 lb. of Asian goods per person in the 18thC.

long distance trade 1500-1850 – its major commodities were sugar, tobacco, tea, coffee, cocoa,

opium, pepper and spices, silk and silver, wider cotton textiles and porcelain.

-none of these were basic necessities – many began and remained luxuries, - many

spread into the consumption patterns of ordinary people in Europe

-many were either addictive or fashion goods – they were goods that people could be

induced to work longer and harder for after their basic needs were met.

They were goods that caused what Jan de Vries called ‘the industrious revolution’.[Jan de Vries, The

Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behaviour and the Household Economy 1650-1800 (Cambridge

University Press, 2008).

What is the ‘industrious revolution’?

The ‘industrious revolution’ describes a change in the behaviour of men, women and children within

household. Demand for new commodities induced women and children to work for cash, for the

market instead of, and in addition to subsistence work for the household. The ‘industrious

revolution’, or more intensive work for the market could provide a pathway to the industrial

revolution.

Textiles

Cottons: varieties: the EIC trading in at least 50 different varieties throughout the seventeenth and

eighteenth centuries.

Cotton calicoes: fashion

Painted and printed calicoes were popular for furnishing and fashion fabrics, but these also had to

be adapted to meet European taste: prints were made on light rather than deep-coloured

backgrounds, and designs were based on European floral motifs. Models and designs were sent to

India.

Printed calicoes succeeded as a fashion textile, widely used in dress of the middling classes and the

elites, then imitated in Europe and traded widely across classes and down to the poor.

But there were market uncertainties: dress fabrics and clothes worn next to the body had to be

adapted.

4

{Giorgio Riello, Cotton: the Fabric that Made the Modern World (2014); John Styles, The Dress of the

People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven, 2008).

Porcelain

European East India Companies brought in 73 million pieces of porcelain 1600-1800. Private traders

multiplied this by several times. Porcelain imports became connected with the tea trade, the driving

force of the China trade from the later 17thC.

Development of export-ware: by the mid eighteenth century varieties of porcelain were brought in

by the private trade that was allowed to employees of the East India Companies; standard lots were

brought in the official trade of the EICs.

Dinner services and armorial porcelain were developed and became popular trade items.

The porcelain trade developed with the tea trade. This increased steadily from 1650-1750, then

exponentially after. All the trading companies took part in the tea trade, but much of the tea was

traded or smuggled to Britain and her colonies.

Robert Finlay, ‘The Pilgrim Art: the Culture of Porcelain in World History’, Journal of World History, 9

(1993), pp. 141-188.; Anne Gerritsen and Stephen McDowall, ‘Material Culture and the Other:

European Encounters with Chinese Porcelain 1650-1800’, Journal of World History, 23, 2012, pp. 87113.

4. European Consumption

Why were Asian goods so desirable?

This market was about luxury, fashion and addiction to tea (and with this Caribbean sugar). This was

a breakable, fragile material culture.

Europeans developed a culture in which exotic goods made sense. More people, especially in

specific places with higher discretionary incomes wanted more choice.

What was in the minds of Europeans encountering strange goods from chocolate and rhubarb to

cottons and porcelain. This was about a self-society interaction. A desiring, stimulus seeking self

developed in tandem with social awareness.

The close urban integration of towns and cities in the Low Countries and Britain provided a context

for the sociability that fostered new experiences of consuming Asian goods. This also spread in

France, and in other ways in Southern and Central Europe, but we still know less about this. That

sociability demanded goods that signalled gentility, politeness and respectability, and increasingly

from the mid eighteenth century, sensibility.

Imitation, Substitution and Industrialization

the impact of the trade was to give rise to new consumer wants – but also to initiatives to

produce these goods or close substitutes elsewhere.

some markets became saturated – such as that for pepper.

5

coffee, sugar and indigo production were transplanted to the Caribbean; tea was

transplanted to British-dominated colonial India.

European silk, porcelain and cotton industries arose to substitute for Asian goods

The result of these initiatives to substitute for Asian goods was to initiate leading industries into

industrialization.

Asia was neutralised: Printed calicoes became ‘English’; porcelain was integrated into an earlier

material culture of glass and silverware.

[Anne McCants, ‘Poor Consumers as Global Consumers: the Diffusion of Tea and Coffee Drinking in

the Eighteenth Century’, The Economic History Review, 61 (2008).

John Styles, The Dress of the People (2008)

Threads of Feeling – online exhibition]

Other Parts of Europe

Asia goods played sometimes similar, sometimes distinctive parts in other parts of Europe, especially

Southern Europe. We know much less about this. There is much new research to do on

consumption and wider sociability in these parts of Europe, and especially on the reception of Asian

goods in Europe.