Document 12816650

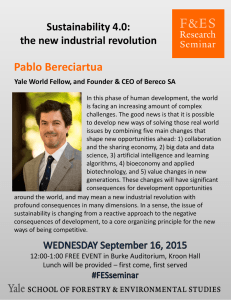

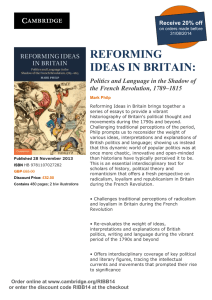

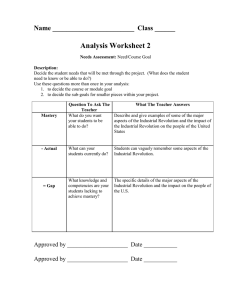

advertisement