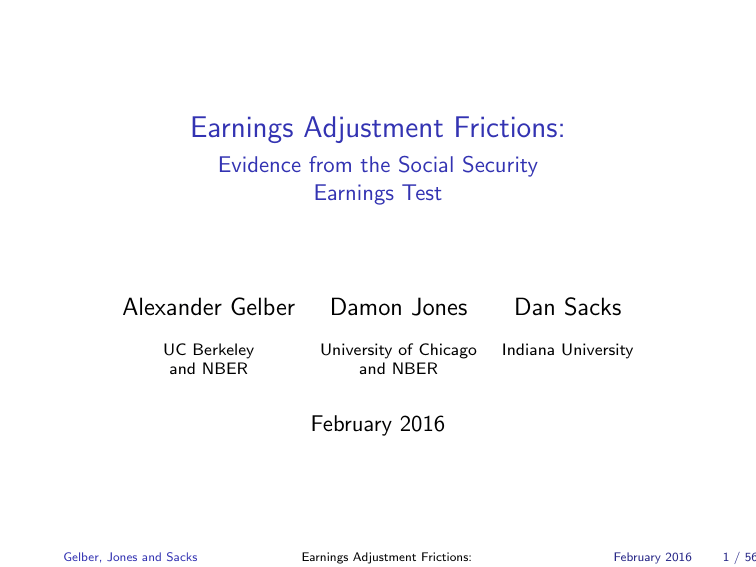

Earnings Adjustment Frictions: Alexander Gelber Damon Jones Dan Sacks

advertisement

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

Evidence from the Social Security

Earnings Test

Alexander Gelber

Damon Jones

Dan Sacks

UC Berkeley

and NBER

University of Chicago

and NBER

Indiana University

February 2016

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

1 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

2 / 56

Introduction

Motivation

I

Social Security Policy Parameter: When to begin payments?

I

I

I

Our project aims to:

I

I

I

Should payments be conditional on earnings while retired?

Behavioral response of earnings is key to designing policy

Document presence of frictions in adjusting earnings in the U.S.

Estimate adjustment cost and earnings elasticity simultaneously using

variation from tax kinks

Methodology for estimating adjustment cost and elasticity applicable

to many other policy contexts

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

3 / 56

Introduction

Motivation

I

Recent papers have studied how barriers to adjustment:

I

I

I

Build upon existing literature on fixed costs (e.g. Arrow et al. 1951;

Caplin 1985; Grossman and Laroque 1990)

I

I

I

Drive heterogeneity in elasticity of earnings with respect to taxes across

contexts (Chetty et al. 2011; Chetty 2012; Chetty et al. 2012; Chetty,

Friedman, and Saez 2013)

Govern the welfare implications of taxes (Chetty, Looney, and Kroft

AER 2009)

Estimate fixed cost in the context of earnings determination

Use non-linear budget set kinks created by tax policy for identification

Extend existing bunching methods to:

I

Apply to budget set kinks

I

I

I

Kleven and Waseem (QJE 2013) innovate method to use notch to

estimate elasticity and inert share

We estimate elasticity and adjustment cost

Exploit dynamic changes in bunching across policy regimes & time

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

4 / 56

Introduction

Our Context

I

Social Security Annual Earnings Test (AET) reduces OASI benefits

when individuals claim (age 62+) and earn above exempt amount

I

I

I

Creates kinks in budget constraint

Actuarial adjustment/Delayed Retirement Credit: will discuss in detail

Response widely studied (e.g. Burtless and Moffitt 1985; Friedberg

1998, 2000; Song and Manchester 2007)

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

5 / 56

Introduction

Our Context

I

AET is particularly fruitful policy to study

I

I

I

Administrative panel data on earnings from Social Security

Administration are accurate and have large sample size

Large changes in AET policy across groups and over time

Hard to find variation in taxes that allows for credible estimation of

elasticities

I

I

I

Kinks in tax schedule helpful (Saez AEJ 2010)

However, little evidence in U.S. of reaction to kinks other than

self-employed, where reaction is largely tax avoidance and evasion

(Chetty, Friedman, and Saez 2013)

AET creates one of few known kinks in U.S. that influences earnings of

non-self-employed (as we show)

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

6 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

7 / 56

Empirical Framework

Basic Framework

I

Individuals ”bunch” (i.e. cluster) at the AET exempt amount

I

Intuition:

I

I

I

I

I

BRR rises (from zero to a positive level) at exempt amount: z ∗

For many people, worth it to earn more at the margin when benefit

reduction rate is zero (below exempt amount) but not at BRR in the

region above the exempt amount

This produces “bunching” in the earnings distribution at the exempt

amount as people cluster near this earnings level

Define B as the share of population bunching, and h0 (z ) as the ex

ante density of earnings

Note: AET is not a tax

I

I

Not administered through tax system

Borrow terminology from tax literature given applicability of methods

for estimating elasticities and adjustment costs more broadly

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

8 / 56

Empirical Framework

Characterizing the earnings response

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

9 / 56

Empirical Framework

Characterizing the earnings response

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

10 / 56

Empirical Framework

Characterizing the earnings response

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

11 / 56

Empirical Framework

Characterizing the earnings response

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

12 / 56

Empirical Framework

Quantifying the Amount of Bunching

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

13 / 56

Empirical Framework

Estimating Adjustment Dynamics

I

We report the amount of bunching, normalized by the density of

earnings at z ∗ , i.e. b = B/h (z ∗ )

I

Approximately the earnings adjustment of the highest earning buncher

(4z ∗ )

I

We estimate excess bunching on repeated cross sections occurring

m = 0, 1, 2... years after change in policy that individuals face

I

We look at how excess bunching varies with m

I

Cleanest evidence from kinks disappearing — there should be no

bunching and we can measure the amount of time it takes for bunching

to disappear

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

14 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

15 / 56

Social Security Earnings Test

Social Security Earnings Test

I

For earnings above threshold, AET reduces current SS benefits

I

Reduction rate and exempt amount vary by age and year

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

16 / 56

Social Security Earnings Test

Earnings Test Changes

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

17 / 56

Social Security Earnings Test

Social Security Earnings Test Features

I

For claimants under NRA, actuarial adjustment: losing benefits due to

AET causes upward adjustment to reduction factor that affects later

benefits

I

I

I

I

If earn any amount above AET exempt amount, future benefits

increased (relative to earning under exempt amount)

Future benefits increased by 5/9 of percent per month with reduction

due to AET

Delaying claiming actuarially fair for average worker

For those Normal Retirement Age (NRA)+ 1972-2000, DRC: losing

benefits due to AET causes upward adjustment that affects later

benefits

I

Future benefits only raised due to the DRC when earnings are

sufficiently high that the individual receives no OASI benefits in a given

month

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

18 / 56

Social Security Earnings Test

Social Security Earnings Test Features

I

Despite actuarial adjustment and DRC, individuals may respond to

AET because:

I

I

I

I

I

Over NRA: AET on average roughly actuarially fair only beginning in

the late 1990s

Expected lifespan short

Liquidity constraints

High discount rate

Not understanding AET or other aspects of OASI rules

I

I

I

Liebman and Luttmer 2011; Brown, Kapteyn, Mitchell, and Mattox

2013

No benefit enhancement if NRA+ and near the exempt amount

Follow approach in most previous literature and do not attempt to

distinguish these reasons

I

Gelber, Jones, and Sacks (2014) investigate certain mechanisms

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

19 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

20 / 56

Data

Social Security Master Earnings File

I

Social Security Administrative Data

I

1% extract of SS claimants

I

Complete earnings history 1951-2006 of calendar year earnings for

each SSN in sample

I

Not manipulable through deductions, credits, etc.

I

Key covariates: earnings, date of birth, when claiming began, SS

benefits

I

Since 1978, ET has been assessed on earnings in each calendar year,

which is the same time frame (i.e. calendar year) as earnings are

observed in our data

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

21 / 56

Data

Data

I

Focus on ages 62-69 (but sometimes look at other ages)

I

Individuals who claim by age 65

I

Positive earnings

I

For results by age, look within a policy regime (e.g. 1983-1989,

1990-1999, 2000-2003)

I

Pool men and women

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

22 / 56

Data

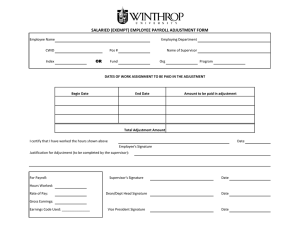

Summary Statistics, SSA Master File: Mean (SD)

Ages 62-69

Mean Earnings

29,892.63

(783,842.99)

25th Percentile

50th Percentile

75th Percentile

5,887.75

14,555.56

35,073.00

Fraction Male

0.57

Observations

376,431

1% sample, 1978-2005, conditioned on claiming SS benefits by age 65; 2010 dollars

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

23 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

24 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 59

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 60

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 61

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 62

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 63

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 64

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 65

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 66

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 67

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 68

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 69

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 70

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 71

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 72

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Bunching by Age - 73

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

25 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Responses by Age (1990-99)

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

26 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Responses by Age (1990-99)

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

27 / 56

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Summary

I

Substantial bunching from 62-69

I

Continued bunching at 70 and 71

I

No significant evidence of bunching starting at age 72

I

Dip in bunching at age 65 (kink moves)

I

Results are robust to Binsize, degree of polynomial and excluded

I

These changes are anticipated (i.e. an individual who knew about the

parameters of AET law would have anticipated the changes)

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

28 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

29 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

I

First review results in a frictionless model

I

Next compare two thought experiments in the presence of a fixed

adjustment cost

1. Moving from no kink to a kink

2. Moving from a larger kink to a smaller kink

I

Extend to a dynamic setting

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

30 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

I

Individuals maximize u (c, z; a) s.t. c = (1 − τ ) z + R

I

I

I

I

Saez (2010) model

Earning generates disutility: z

Indexed by ability: a

Individuals must incur a cost of φ in order to change earnings

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

31 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Frictionless

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

32 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Frictionless

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

33 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Frictionless

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

34 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Cross Section

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

35 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Cross Section

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

36 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Cross Section

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

37 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Cross Section

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

38 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Kink Variation

I

Now imagine we introduce a larger kink (K1 ) first, and then transition

to a smaller kink (K2 )

I

We will now observe attenuation in the change in bunching, i.e. less

”debunching” than we would expect

I

This leads to ”excess” bunching left over at the kink when moving

from K1 to K2

I

as compared to moving from no kink to K2

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

39 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Sharp Change

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

40 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Sharp Change

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

41 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Sharp Change

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

42 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Sharp Change

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

43 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Intuition

I

Two moments (B1 & B̃2 ), two unknowns (ε & φ)

I

I

Inertia due to an adjustment cost leads to an excess amount of

bunching after a kink in the budget set becomes less sharply bent (or

disappears altogether).

I

I

Identification intuitively arises from two sources: the amount of

bunching in a single cross-section, and the change in the amount of

bunching from one cross-section to another (which is attenuated by

adjustment cost)

Our primary estimation method uses the degree of such inertia (in

combination with the initial amount of bunching at the kink) in

estimating the size of the adjustment cost (and elasticity)

Resulting parameters mean that bunching in the time frame studied

can be predicted if individuals faced the estimated adjustment cost

and elasticity

I

I

In the spirit of Friedman (1953)

Study immediate adjustment to a policy change, so parameters pertain

to frictions faced in immediately adjusting

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

44 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Dynamic Extension

I

So far, rely on moments just before and after the policy change

I

Two additional patterns:

I

I

I

Delayed adjustment in subsequent period

Lack of anticipatory response

Extend model to dynamic context

I

I

Stochastic adjustment process that generates slow reaction to policy

change

Assume agents are myopic

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

45 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Dynamic Extension

I

vt = u (ct , zt ; a) − φ̃t · 1 {zt 6= zt −1 }

I

φ̃t = φ > 0 with probability π t −t ∗ , otherwise φ̃t = 0

I

I

τ 0 in period 0, τ 1 until period T1 , τ 2 thereafter

1/ε

u (ct , zt ; a) = c − 1+a1/ε za

I

zt − T (zt ) − ct ≥ m

I

Optimal strategy:

I

I

I

Adjust if 4u > φ̃t

Any ”active” adjustment (i.e. when φ̃t > 0) takes place immediately

Thereafter, only adjust when φ̃t = 0

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

46 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Dynamic Extension

I

For 0 < t ≤ T1 :

B1t

I

t

t

j =1

j =1

= ∏ π j · B1 + 1 − ∏ π j

!

· B1∗

For t > T1 :

B̃2t

t −T1

=

∏ πj ·

j =1

"

T1

B̃2 +

1 − ∏ πj

!

#

[B1∗

− B1 ] + 1 −

j =1

t −T1

∏ πj

As t → ∞, B1t → B1∗ and B̃2t → B2∗

I

Nests frictionless model (π = 0) and static model (π = 1)

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

· B2∗

j =1

I

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

!

February 2016

47 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Dynamic Extension

I

Observe bunching around 2+ policy changes

I

I

π’s estimated relative to each other from pattern of bunching over time

Delay in adjustment corresponds to higher π

I

Higher φ means more inertia in all periods until bunching is fully

adjusted

I

Higher ε means more bunching once bunching is fully adjusted

I

Comparative static model transparently illustrates the basic forces

I

Estimation of more dynamic model requires more moments from the

data

I

Assumption that ability fixed over time may be more plausible in static

model when we use two cross-sections from adjacent time periods

I

But dynamic model allows more direct account of forces determining

the time pattern of bunching.

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

48 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Identification

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

49 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Elasticity Estimates by Year, Saez (2010) Method

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

50 / 56

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Estimation

I

Empirically observing bunching amounts B = (B1 , ..., BL )

I

Nonparametrically estimate H0 (·) — and therefore h0 (·) using age

72 earnings

I

Given a value for (ε, φ), z ∗ , T (z ) and H0 we can calculate B̂

I

Finally:

0

ε̂, φ̂ = arg min B̂ (ε, φ) − B W B̂ (ε, φ) − B

ε,φ

I

Similar method for estimation of (ε, φ, π 1 , π 2 , π 3 )

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

51 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

52 / 56

Results

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: 1990 Policy

Change

Baseline

Bandwidth = $1,600

Benefit Enhancement

(1)

(2)

ε

φ

0.35

[0.31, 0.43]

0.33

[0.29, 0.43]

0.58

[0.50, 0.72]

$278.25

[57.68, 390.77]

251.45

[33.57, 406.70]

$150.91

[17.31, 225.54]

(3)

(4)

ε|φ = 0

1990

1989

0.58

[0.45, 0.73]

0.55

[0.43, 0.72]

0.87

[0.69, 1.11]

0.31

[0.24, 0.39]

0.30

[0.23, 0.40]

0.52

[0.41, 0.66]

All estimates are significantly different from zero at the 0.01 level.

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

53 / 56

Results

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost: Dynamic

Model

(1)

Baseline

Bandwidth $1.6K

Benefit

Enhancement

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

ε

φ

π1

π1 π2

π1 π2 π3

0.36

[0.34, 0.40]

0.36

[0.34, 0.39]

0.59

[0.54, 0.64]

$243.44

[34.07, 671.19]

98.61

[19.48, 400.52]

$52.55

[17.65, 168.52]

0.64

[0.39, 1.00]

0.88

[0.40, 1.00]

1.00

[0.76, 1.00]

0.22

[0.00, 0.14]†

0.52

[0.043, 1.00]

0.37

[0.00, 1.00]

0.00

[0.00, 0.14]†

0.00

[0.00, 0.071]

0.00

[0.00, 0.084]

All estimates are significantly different from zero at the 0.01 level, except for

†

Model Fit

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

54 / 56

Outline

Introduction

Empirical Framework

Social Security Earnings Test

Data

Documenting Adjustment Frictions

Estimating Elasticity and Adjustment Cost

Results

Conclusion

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

55 / 56

Conclusion

Findings

I

Evidence of earnings adjustment frictions in U.S.

I

Develop method to estimate elasticities and adjustment costs in

presence of kinks in budget set

I

Baseline: Elasticity = 0.35 and adjustment cost = $280

I

I

I

I

Delays in reacting show that the short-run impact of policy can be

substantially attenuated

I

I

Results can be used as an input into calculating score of eliminating

AET

Two of the parameters in a welfare analysis of the AET

If assumed no adjustment cost: elasticity = 0.58

Frustrates goal of immediately affecting earnings as envisioned in many

recent fiscal policy discussions

Methodology for calculating elasticity and adjustment cost more

broadly applicable to many policies

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

56 / 56

Conclusion

Simulated Bunching Using Dynamic Model

Gelber, Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

56 / 56

Conclusion

Simulated Bunching Using Dynamic Model

Dynamic

Results

Gelber,

Jones and Sacks

Earnings Adjustment Frictions:

February 2016

56 / 56