Anti-smoking policies and smoker well-being: evidence from Britain IFS Working Paper W13/13

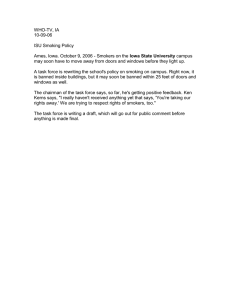

advertisement