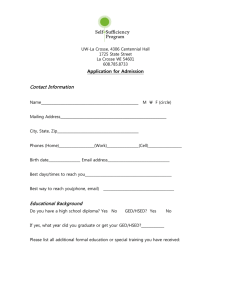

8. State support for early childhood

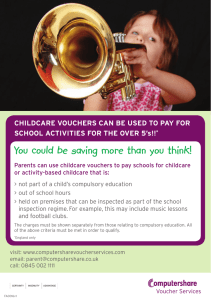

advertisement