3. Fiscal repair: painful but necessary Summary •

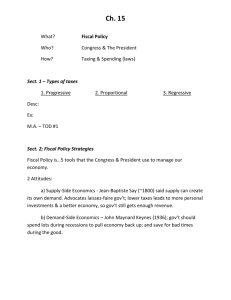

advertisement