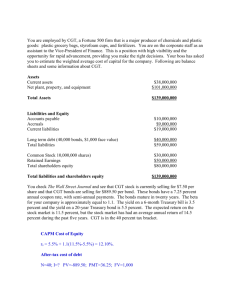

10. Capital gains tax Summary

advertisement