12 Administration and Compliance Jonathan Shaw, Joel Slemrod, and John Whiting

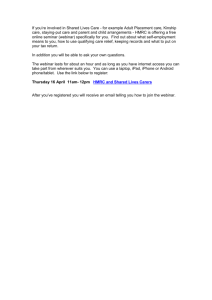

advertisement