8 Taxation of Wealth and Wealth Transfers

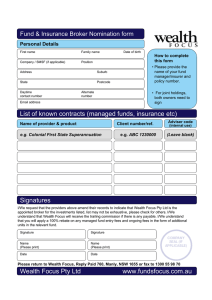

advertisement