Legislative Malfeasance and Political Accountability

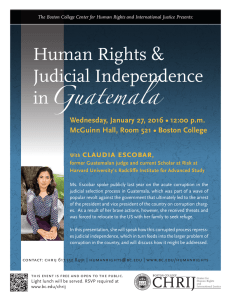

advertisement