ndeavor E Breakthroughs of 2004

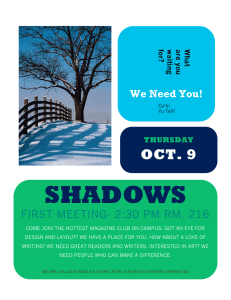

advertisement