How people use temporary post- disaster open spaces: Andreas Wesener

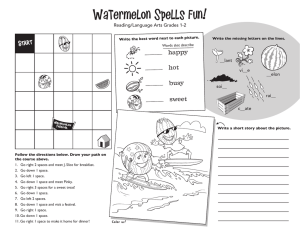

advertisement