Water Allocation: A Strategic Overview P

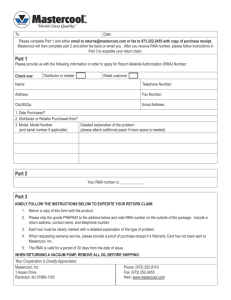

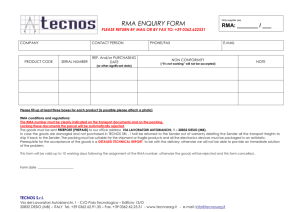

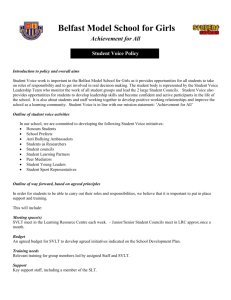

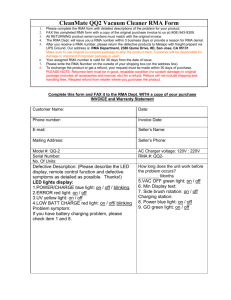

advertisement