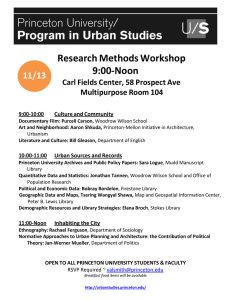

Education and Innovation Enterprise and Engagement The Impact of Princeton University

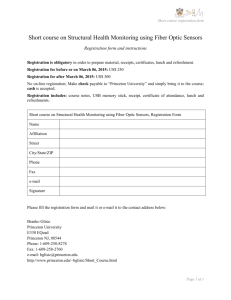

advertisement