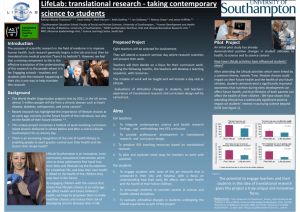

University of Southampton Economic Impact of the University of Southampton

advertisement