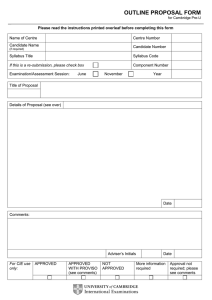

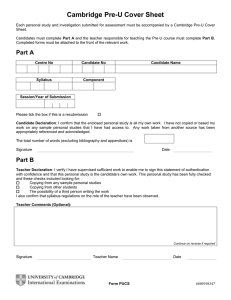

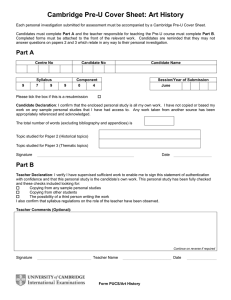

Cambridge Pre-U Syllabus Cambridge International Level 3 Pre-U Certificate in

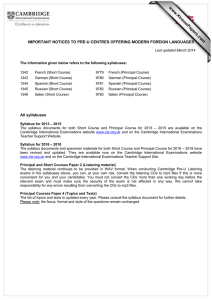

advertisement