JTAP On-Line Teaching: Tools and Projects Stuart Lee

advertisement

JTAP

JISC Technology

Applications

JISC Technology

Applications

Programme

P

On-Line Teaching: Tools and

Projects

Stuart Lee

Paul Groves

Chris Stephens

Susan Armitage

Oxford University

Report: 28

JISC Technology

Applications Programme

Joint Information Systems Committee

May 1999

On-Line Teaching: Tools and

Projects

Stuart Lee

Paul Groves

Chris Stephens

Susan Armitage

Oxford University

The JISC Technology Applications Programme is an initiative of the Joint

Information Systems Committee of the Higher Education Funding Councils.

For more information contact:

Tom Franklin

JTAP Programme Manager

Computer Building

University of Manchester

Manchester

M13 9PL

email: t.franklin@manchester.ac.uk

URL: http://www.jtap.ac.uk/

Contents

FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................. 1

BACKGROUND ISSUES .......................................................................................................... 3

A. The Dearing Report and After ................................................................................................................................. 3

B. The Initial Backlash.................................................................................................................................................. 7

C. Cometh the Internet, Cometh the Solution? .......................................................................................................... 9

D. Why Do Teachers Use the Internet?..................................................................................................................... 11

E. Is the Internet Effective?........................................................................................................................................ 12

F. Resource-Based Learning (RBL) .......................................................................................................................... 13

G. What Should One Use? ......................................................................................................................................... 14

H. Is It Easy To Be Successful?................................................................................................................................. 14

EMAIL LISTS - VIRTUAL LITE............................................................................................... 17

A. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 17

B. Using Mailing Lists: Some Case Studies ............................................................................................................. 17

C. Creating A List........................................................................................................................................................ 22

D. Tips for a Successful List...................................................................................................................................... 22

COMPUTER MEDIATED COMMUNICATION (CMC) ............................................................ 24

A. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 24

B. Potentials ................................................................................................................................................................ 24

C. Limitations .............................................................................................................................................................. 25

D. Models of Use ......................................................................................................................................................... 26

E. Examples of use ..................................................................................................................................................... 28

F. Critical Success Factors ........................................................................................................................................ 32

G. Tutor and Learner Roles........................................................................................................................................ 34

H. Computer Managed Learning Environments ...................................................................................................... 35

I. CMC Links ................................................................................................................................................................ 36

THE WORLD-WIDE WEB: ITS USES AS A TEACHING TOOL ........................................... 38

A. Why Use the Web? ................................................................................................................................................. 38

B. Resource-Based Learning..................................................................................................................................... 38

C. Navigating the Web ................................................................................................................................................ 41

D. Some Ideas for Web Pages ................................................................................................................................... 42

E. Creating Web Pages............................................................................................................................................... 43

F. Further Reading and Sites of Interest: ................................................................................................................. 46

MUDS, MOOS, WOOS AND IRC............................................................................................ 48

A. What Are These 'TLAs'? ........................................................................................................................................ 48

B. What Is A MUD/MOO? ............................................................................................................................................ 48

C. Basic MUD/MOO Concepts.................................................................................................................................... 48

D. The Textual Model .................................................................................................................................................. 49

E. Technology Requirements .................................................................................................................................... 52

F. WOOs'Webbified' MOO Environments ................................................................................................................. 53

G. Communication, Social Interaction and Sense of Space ................................................................................... 56

H. Building Objects..................................................................................................................................................... 57

I. Diversity University: An Example Educational MOO ........................................................................................... 58

J. Some Comments About Teaching in MOOs ........................................................................................................ 59

K. MOO & MUD Client Software................................................................................................................................. 60

L. Setting-up Your Own Educational MOO\WOO ..................................................................................................... 61

M. Quick Set-up Guide................................................................................................................................................ 62

N. Useful Documents.................................................................................................................................................. 66

O. Useful Mailing Lists ............................................................................................................................................... 67

P. MOO Server Software............................................................................................................................................. 68

Q. Some Educational-Related MOOs ........................................................................................................................ 69

INSTRUCTIONAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS (IMS)............................................................ 73

A. What is IMS? .......................................................................................................................................................... 73

B. The Potential of IMS ............................................................................................................................................... 74

C. IMS: Some Reservations ....................................................................................................................................... 74

COMPUTER-AIDED ASSESSMENT (CAA) .......................................................................... 76

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY...................................................................................................... 78

Foreword

'Technology has revolutionised the way we work and is now set to transform education.

Children cannot be effective in tomorrow's world if they are trained in yesterday's skills.

Nor should teachers be denied the tools that other professionals take for granted.

The Grid [National Grid for Learning] will be a way of finding and using on-line learning

and teaching materials. It will help users to find their way around the wealth of content

available over the Internet.

By 2002, all schools will be connected to the superhighway, free of charge; half a million

teachers will be trained; and our children will be leaving school IT-literate, having been

able to exploit the best that technology can offer. '

Tony Blair, 7 October 1997

'Tools as powerful as networked computers are going to transform human

communication. This transformation will bring with it both loss and gain. Every

revolution in communication has both added to the power and range of what is

communicated, and taken away some of the intimacy.

Higher Education is challenged as it has not been in a generation to prove its value and

cost-effectiveness. It's a blessedly lucky time for this new toolbox to show up, and I

would feel like an idiot if I didn't do everything in my power to use it to its best

advantage'.

Prof. J. J. O'Donnell (http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu:80/jod/)

The aim of this report is simple. In an age where the use of Computers and Information Technology is

almost regarded as essential to every daily activity, academics are coming under increasing pressure

(e.g. the opening declaration from the Prime Minister) to adapt their teaching to accommodate the new

technologies. This report focuses on a single, but arguably the most important area - the Internet. We

will look at the various ways the Internet is being used for teaching, and at projects under development

at the moment.

1

The report is an update of the previous title Existing Tools and Projects for On-Line Teaching (eds.

Groves, Lee, and Stephens, 1997) and supersedes that publication. Through a generous grant by the

JISC Technologies Applications Programme we have been able to extend the scope of the report to

look at issues arising post-Dearing, computer-based communication, and IMS (to name but a few). All

references and links have been checked and updated in order to be accurate at the date of publication.

In addition, this report should be read in conjunction with On-Line Tutorials and Digital Archives (Lee

and Groves, 1998; http://www.jtap.ac.uk/reports/index.htm) which points to other practical issues. We

hope this guide proves to be a useful introduction to academics who wish to use the Internet for their

teaching. However, the editors would be very interested to hear from colleagues in other subjects who

might wish to contribute similar examples from the Sciences and Social Sciences.

Stuart Lee

Project Manager, JTAP ‘Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature’ (http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/)

Dr Stuart Lee is Head of the Centre for Humanities Computing, part of the Humanities Computing Unit

at Oxford University Computing Services (Oxford University Computing Services, or OUCS). He was

the Manager for the J-TAP project 'Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature'. Contact:

Stuart.Lee@oucs.ox.ac.uk; see: http://users.ox.ac.uk/~stuart/.

Mr Paul Groves is working on the Humanities Computing Development Team (based at OUCS). He

was the Project Officer for 'Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature'. Contact:

Paul.Groves@oucs.ox.ac.uk; see: http://info.ox.ac.uk/oucs/humanities/staff/paul.html.

Mr Chris Stephens is Humanities IT Support Officer at the Centre for Humanities Computing (OUCS).

Contact: Christopher.Stephens@oucs.ox.ac.uk; see:

http://info.ox.ac.uk/oucs/humanities/staff/chris.html.

Ms Susan Armitage (http://www.lancs.ac.uk/staff/cpasea) works for Information Systems

Services(http://www.lancs.ac.uk/users/ISS/) at Lancaster University (http://www.lancs.ac.uk/).

2

Background Issues

A. The Dearing Report and After

The most important report to focus on Higher Education for some years, commonly known as the

Dearing Report, was published in 1997. More correctly entitled the ‘National Committee of Inquiry

into Higher Education’ by Sir Ron Dearing (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/ncihe/) it formulated 93

recommendations, of which 15 related to 'Computers and Information Technology' (or C&IT). The

official Government response to Dearing appeared initially in the form of 'Higher Education for the

21st Century' (July, 1997; http://www.open.gov.uk/dfee/highed/index.htm) and then, in a second

revised version which included full responses after a consultation period (February, 1998;

http://www.lifelonglearning.co.uk/dearing/index.htm). In the original 1997 reply David Blunkett, the

Secretary of State for Education and Employment, remarked in his foreword:

'Our people hold the key to our future. We have already set out an ambitious

agenda to raise standards in our schools.

But that is not enough. We need to ensure that everybodywhatever their age or

backgroundhas access to lifelong learning, with education and training throughout

their life. '

This was the start of a series of initiatives to promote lifelong learning, and resource based learning. As

Jackson and Parker note:

'Following the publication of the Dearing Report (1997) it is clear that the

continued expansion of student numbers and the increase in part-time students and

students from non-traditional backgrounds is likely to lead to further development

of student-centred and resource based learning. i '

In general the suggestions put forward by the Dearing Report were accepted (although there was often

no indication as to any additional funding which might be found to help implement them). With

relation to this report the most pertinent recommendations were as follows:

That…

[Recommendation 9] students and staff should receive adequate training in C⁢

3

[Recommendation 14] an Institute for Learning and Teaching in Higher Education should be

established (this will help accredit university teachers but will also tackle the use of IT in

teaching);

[Recommendation 15] a system of kite-marking computer-based teaching material should be

brought in;

[Recommendation 42] senior managers in HE should have a deep understanding of C⁢

[Recommendation 49] all students will have access to a networked PC by 2000/2001 and all

students will own their own PC by 2005/2006.

Dearing, in many ways, heralded the start of a quite breathtaking series of reports and initiatives

looking at education (at all levels), which embraced in various ways the possibilities of C&IT. The

Government set up the National Advisory Group for Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning,

which produced its first report in November 1997 entitled 'Learning for the 21st Century' (commonly

known as the Fryer report, after the chair of NAGCELL Professor R. H. Fryer;

http://www.lifelonglearning.co.uk/nagcell/index.htm). Following this there was 'The Learning Age' a

Green paper on Lifelong learning published on the 25 February 1998

(http://www.lifelonglearning.co.uk/greenpaper/index.htm) which in its summary noted the possibilities

of:

'….new opportunities for people in further and higher education. They will help

people to gain technician and higher level skills, including postgraduate

development…one of the best ways to overcome some of the barriers to learning

will be to use new broadcasting and other technologies. We expect their role in

learning more generally to increase significantly'

UK Department for Education & Employment’s Lifelong Learning Page

(http://www.lifelonglearning.co.uk/, Chapter 1, Section 5).

Early 1998 also saw Baroness Kennedy’s report 'Learning Works' on Further Education for England

(summary at http://www.niace.org.uk/Organisation/advocacy/kennedybriefing.htm) and the

Government's reply (http://www.lifelonglearning.co.uk/kennedy/index.htm) was published in February

1998. This continued the process of assembling the jigsaw of what can only be described as one of the

most concerted attempts to investigate education on all levels since the end of the Second World War ii .

As already noted at the beginning of this report the National Grid for Learning

(http://www.open.gov.uk/dfee/grid/) seems to be the focal point for many sweeping observations. It

aimed to:

4

‘focus initially on teacher development and the school sector and extend to lifelong

learning...National and local museums, galleries and other content providers will

have an important part to play. We intend that libraries with their vast stores of

information and accessibility to the public, will be an integral part of the Grid. In

this way the Grid will make available to all learners the riches of the world's

intellectual, cultural and scientific heritage.’

It went on to state that:

'Learning through ICT not only offers the chance to become proficient in the skills

needed in the world of work. It enhances and enriches the curriculum, raising

standards and making learning more attractive. The best educational software is

not an alternative to books or class teachers - it is a new chapter of opportunity.

The Grid will mean that:

* teachers will be able to share and discuss best practice with each other and

with experts while remaining in their schools;

* materials and advice will be available on-line - when learners want them - to

help develop their literacy and numeracy skills, including in their own time;

* children in isolated schools will be able to link up with their counterparts'

curriculum, to help them to work together and gain the stimulus they need;

* language learners will be able to communicate directly with speakers of the

target language;

* learners at home or in libraries will be able to access a wider range of quality

learning programmes, materials and software.

All learning on the Grid will be able to be tailored to the interests and abilities of

the individual. '

(See the National Grid For Learning Page at

http://www.open.gov.uk/dfee/grid/offer.htm)

Once again one can see the focus on lifelong and resource based learning. To summarise, educational

opportunities need to expand to bring in a greater number of members from all areas of society. This in

turn means a ‘release’ of educational resources to a wider market. Technology, it is stated, can assist in

5

this by creating a digital infrastructure, e.g. network or grid, to increase access. In particular, with

lifelong learning, the advantages are spelt out as opening up:

'new horizons for people at home whose curiosity had been aroused by a television

programme and could instantly follow up aspects of it through interactive services.'

Connecting the Learning Society (http://www.open.gov.uk/dfee/

grid/content.htm) iii .

The effects of these initiatives are already being felt by academics around the country as pressure

mounts to become part of this digital world. A small but illuminating example can be found in the

CVCP’s responses to the moves for accreditation of lecturers (as proposed by Dearing with the ILTH).

2.6 Candidates for Associate membership of the Institute might be expected to

demonstrate how, in their work as a teacher, they have a knowledge

and understanding of:

the subject material which they will teach to their student groups

how their subject is learned and taught

how students learn, both generically and in their subject

teaching approaches

the use of learning technologies

techniques for monitoring and evaluating their own teaching

their institution's mission and how it affects teaching and learning strategies

implications of quality assurance for practice

regulations, policies and practices affecting their own work

(iii) They might be expected to maintain a current understanding of teaching styles

for individuals and groups.

This might include methods which, for example:

support a deep approach to learning;

encourage the development of knowledge and skill in adult learners;

promote active learning;

develop students as life-long learners;

encourage the development of appropriate relationships between theory and

practice, such as problem-based and work-based learning;

make appropriate use of learning technologies

6

Booth, C., Accreditation and Teaching in Higher Education: Final Report to The

Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals of the Universities of the United

Kingdom (May 1998, http://www.cvcp.ac.uk/boothfin.html)

That the major funding bodies see the new technologies as both exciting and possibly the only way to

solve some of the problems besetting Higher Education at the moment is without doubt. In its report

Exploiting Information Systems in Higher Education (1995) (http://info.mcc.ac.uk/NTI/JISC/JISCIssues.html) JISC (Joint Information Systems Committee) saw its key objectives as including 'the

educational environment and quality of teaching and learning', identifying the need for developing 'a

plurality of network provision to meet the diverse needs of the community' and 'access to a

comprehensive and co-ordinated collection of electronic information'. At the same time 'an expanded

'reach' of networking is vital if teaching material and on-line tutorials are to be delivered to students'

(M. Read 'The JISC Five-Year Strategy: 1996-2001', TLTP Newsletter 8 (Autumn, 1996) p.20).

To help in this JISC have established such support groups as JISC-ASSIST which aims to: ‘close the

gap between the availability of Communications and Information Technology products and services

and the Higher Education’. JISC has funded numerous projects through its Technologies Applications

Programme (JTAP), to implement C&IT in various ways, and is focusing also on increasing the access

to digital resources through the Distributed National Electronic Resource (administered by JISC’s

Committee on Electronic Information).

Yet caution is called for. Change, invariably, implies new costs (financial and time), and at the moment

this is something most higher education institutions can ill afford to take on board. As Diana Laurillard

suggests:

'We know we have to expand IT. We know that costs cannot continue to rise with

increasing student numbers. We know we have to use IT and that IT is very costly.

How do we square that circle?' 'Recommendations of the National Committee'

Laurillard, D. in IT & Dearing: The Implications for HE (ed.) H. Beetham (CTISS,

1997), pp. 6-16.

B. The Initial Backlash

In 1994 at the opening of the publication Higher Education 1998 Transformed by Learning Technology

(eds.) Darby and Kjöllerström, the two editors of the report, presented a fictional account of how they

perceived a 'typical' student might study in 4 years time (from then). The fictional student, Carlos,

emerges from his sleep, eats breakfast, and accesses a computer:

7

'His workstation, which he uses for most of his studying, connects to the academic

network using the facilities of his cable TV company'. Carlos is studying Company

Ethics, and is watching some streamed video when at one point he 'has difficulty

with the presentation and repeats a section of it. It is still not clear so he highlights

the notes that he is not following and selects Explain from Guidance menu. Carlos

is asked a few questions and is then offered a choice of three items of background

material. 5 minutes with the first of them is enough to explain the concept he had

not previously encountered and he is able to proceed with the unit' (Darby and

Kjöllerström , p.5).

We are told how Carlos is working full-time for two thirds of the week, his degree is

entirely modularised, and most of his studies are with the fictional 'Open Network

University'. The authors explain that:

'Carlos is enthusiastic about his mode of studying. He finds it hard to conceive

how his parents sat through several hours of lectures a day when they were

students. He has the freedom to study what he wants, when he wants, where he

wants. He also enjoys excellent interaction with his tutors and fellow students

even though he only knows most of them through electronic mail and

teleconferencing links.' (Darby and Kjöllerström, p.6)

To many academics (and one would suggest students also), this is a dystopian rather than utopian

vision. The reduction of staff/student contact to the point of almost non-existence seems far from

attractive to either lecturers or students. The former fear that the skills they have as educators are being

overlooked and that the students may drift harmfully without any guidance and tuition. The latter, the

students, note the financial investment they are being asked to outlay on their education, and do not

equate less contact time with staff as value for money.

In the US recently, the American Association of University Professors circulated a letter after concerns

were raised concerning a US Government white paper which stated that instructional software could

easily substitute for campus-based instruction. It calculated that only 25 on-line courses were needed to

serve about 80% of undergraduate courses. The American Professors, happy to embrace the Internet

and on-line teaching, and recognising that technology has helped 'streamline academic life', were still

concerned enough to state 'high quality teaching, whether done on a distance-learning basis or on a

campus basis, requires contact' (Prof. L. Goodlad) and that 'when they basically want to replace people

with computers, that's where we draw the line...we objected to the extreme views, like beaming an

image of professors to students and thinking that would be a satisfactory way of replacing a face-toface education' (Prof. G. Diment iv ).

8

This report does not celebrate the scenario painted by Darby and Kjöllerström, and perhaps reflects

more the stance adopted by the US lecturers. We intend to show the potential of using the Internet for

teaching, illustrated by good case studies, but at the same time observing the three rules of using

technology for teaching:

1) Technology should not be used to replace teachers or teaching. It should be

used as a supplement to teaching, or as a replacement for the absence of teaching,

i.e. by making material available if a course is not currently being run, or to

remote/life-long learners who do not enjoy the privileges of being linked to an

Education institution.

2) In a similar vein to the theory of Second Best in Welfare Economics, technology

should only be used where a noticeable gain to the teaching quality is evident.

Bearing in mind the considerable costs (both in terms of finances and time) it is not

enough to simply employ IT on the basis that it will not do any harm.

3) Technology should be applied in appropriate stages. It is not essential to use

every bit of new technology at your disposable. Sometimes the most noticeable

effects can be derived from very easy-to-use methods, most noticeably in the area

of computer-mediated communication.'

(Lee, S. D., Forging Links: The Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature Project

(http://www.info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/reports/eurolit.html))

This report seeks to simply provide basic knowledge and training in the light of the external pressures

(noted above) for academics, librarians, etc., to embrace the growing area of C&IT. It is not within the

scope of this report to attempt to influence policy on a national level. Instead this document should be

regarded as a guide or handbook for academics that wish to bring in C&IT into their teaching.

C. Cometh the Internet, Cometh the Solution?

The Internet is seemingly all pervasive, and has reached a level of acceptancy in the public’s eyes that

means it is almost impossible to escape. Nearly every kind of institution or company has a web site of

some form or another, and a growing amount of academic business is performed through electronic

mail. One can not even go to the cinema nowadays without the trailer for future releases advertising a

URL more prominently than some of the actors. Immersed in this environment also, are of course the

students. Since the compulsory introduction of IT into the national curriculum, they will have been

exposed to computers in some form or another by the time they reach higher education. Indeed,

students coming to University in 1999 could well have been as young as 12 or 13 when they first began

9

to access the Web via the popular (but now almost forgotten) browser Mosaic issued by the National

Centre for Super-Computing Applications (NCSA). Faced with pressures from without (i.e. via

Government initiatives, TQAs) and from within (i.e. Vice Chancellors at one extreme and students at

the other) the challenge noted by Professor O’Donnell at the opening of this report becomes all the

more important. Partly this comes from social pressures of wishing to appear up-to-date, and partly it

comes from students themselves who want to feel that they are getting value for money and access to

the latest resources.

After the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik in 1957, the US established the Advanced Research

Projects Agency to investigate ways of increasing the military's use of digital communications .

Although this was a Defence department agency it soon saw the need to bring in the major US research

Universities. In 1969, a four node network (UCLA, Stanford Research Institute, UC Santa Barbara, and

the University of Utah) was established running under a 50kbps circuit. In Gromov v there are details of

one of the first Internet communications. Maintaining communication via the telephone the message

LOGWIN was typed in on one terminal in the hope that it would appear on the screen at the remote

node. The following conversation is recorded:

'We typed an L into our computer and we asked on the phone 'Do you see the L?'

'Yes we see the L' came the response'

'We typed the O' and we asked 'Do you see the O?'

'Yes we see the O'

'Then we typed a G, and the system crashed.'

The network soon expanded to 15 nodes and in 1973 there was the first cross-Atlantic links to England

and Norway. 1981 saw the advent of BITNET ('Because It's Time Network') organised by the City

University of New York with an initial connection to Yale. This network provided accessible electronic

mail and listserv servers. In 1984 JANET (the UK's Joint Academic Network) was established, linking

Higher Education institutions throughout the country, and allowing access to the global Internet.

1992 saw the beginning of the World-Wide Web (although in truth it had been developed at CERN

some years previous, after an initial proposal by Tim Berners-Lee ). The success of the Web was

assured with NCSA's release of its free browser Mosaic in 1993, allowing a user-friendly way of

graphically accessing the many Internet resources that were available. To give some idea of the growth

of the Internet the 4-node network of 1967 grew to 28,174 nodes in 1987 and reached 3,212,000 in

1994. It is now measured at approaching 600 million.

What exactly is the Internet? The Internet stands for 'internetworking', i.e. when two or more computers

are internetworked allowing for communication between them. It is now taken to relate to the global

network that allows you to send a message to a machine elsewhere on the network, in this case a global

one, or to look at information on a remote machine. There is no Internet as such. It is made up a series

10

of Wider Area Networks (e.g. JANET) talking to each other, which in turn are made up of Local Area

Networks (e.g. the network for an individual University), i.e. networks within networks.

D. Why Do Teachers Use the Internet?

The simple and obvious answer to this question is because they are being told to. However, the need to

keep in step with the funding agencies is not reason enough to adopt such a dramatic shift in

pedagogical methods. The Internet provides academics with an opportunity to make their teaching

better, to allow them to teach in different ways to the standard one-to-many lecture, and to reach more

students. Simply put, it allows for the 'maximisation' of learning, which Somekh vi described as:

'There are...two ways in which 'maximization' [of learning] can be measured: either in terms

of the increase in the amount of learning, or in terms of the increase in the quality of learning.'

In other words the Internet allows for a more efficient and interesting way of 'imparting knowledge'

(which is Laurillard's basic definition of teaching as listed in her seminal work from 1993 vii ).

To add to this, the Internet (and most notably the Web) can display the following advantages. In most

cases it is:

* cheap

* easy to use (as both an author and a learner)

* fashionable

* attractive to students

* cross-platform

* suitable for accessing resources of various media

* ideally suited for remote learning, i.e. 'remote' from the classroom either by

location or time

* interlinking providing access to resources held in other subject areas and

institutions

* suited to increasing collaborative work and cross-institution communication

Bill Tait (1997 viii ) notes that traditionally the Internet seemingly provides two options. The first 'is a

form of distance learning in which a tutor places courseware on a Web server where it can be accessed

by remote students' (p.3) identifying the disadvantages of such a system as being expensive if one is to

insure 'enough software to meet the demands of a complete syllabus'. Alternatively there is the

'independent study in which learners search the Internet for materials that are relevant to their interests'.

Again this has disadvantages most notably because the suitability of the material students access cannot

be guaranteed. His solution, which is in keeping with this report, is a combination of the two modes

11

into Internet Based Learning (IBL) 'in which a learner is provided with access to courseware stored on

the campus or the Internet from either location'. A successful teaching model could involve then

'orientating, motivating, presenting, clarifying, elaborating, consolidating, and confirming' (p.4). This

can be married with the pedagogical aims of such Internet-based projects as JTAP's COSE which

outlines:

A largely constructivist view is taken in that learning is seen as an active process in

which learners construct new ideas or concepts based on their existing knowledge

and skills, but it is considered that for true learner autonomy to be achieved a

structured development of essential learning skills is also required. These learning

skills include:

procedural skills

knowledge/memory skills

mental agility

problem solving skills

time management

learning management

organisational skills

(Creation of Study Environments, http://www.staffs.ac.uk/COSE/)

E. Is the Internet Effective?

Oliver and Conole (1998) state that:

'Even a superficial review of methodologies shows that no one approach to

evaluating the use of C&IT is best suited to all the needs or situations which arise.

Instead, each has its own strengths and weaknesses, and has been designed with

specific evaluation needs in mind.' (p.4 ix )

Diana Laurillard writing earlier on the evaluation of the new technologies for educational purposes

implies that the Internet does work as an effective teaching tool but only if certain rules have been

observed. As well as obeying the standard guidelines for computer-aided learning (e.g. a good user

interface, effective navigational tools, etc.) it is imperative that academics consider the following:

* is it clear to the students why they are using this new way of learning?

* is any prerequisite knowledge needed to use the material (e.g. training on e-mail,/web

browsers)?

12

* is there sufficient support (e.g. hardware and software; training; access to experts)?

* has the assessment for the course been redesigned in the light of the introduction of

Internet-based materials?

* have the students been made fully aware of the importance of the course: e.g. is it

essential, important, or simply optional?

Laurillard produced four now much-used models for learning looking at the teacher/student roles. She

has argued that the traditional model of teaching, 'learning through acquisition', is suited to the lecture,

video, broadcast, and publication of lecture notes on the Web. The second model, 'learning through

discussion', is usually face to face but computer-mediated communication can replicate this to a certain

degree. The third, 'learning through discovery', is via the lab, field trip, or computer-aided simulation.

However the fourth model, 'learning through guided discovery' can bring all of the benefits of

computer-aided teaching to the fore x . It is arguable that this model, whereby the teacher acts as the

guide, is hardly revolutionary and has been employed by good pedagogues for centuries, but

nevertheless it ties in with the concept of resource-based learning (see below).

One thing which is clear from observation of the ways students learn is that they strongly object to any

idea that they are being used as guinea-pigs to simply test teaching methods for future generations. If

they can see no benefit for themselves they will react unfavourably. To avoid this it is imperative that

the students are motivated. A lot of the knowledge conveyed in classes is only of use to them for future

activities, and therefore one can not rely on simple 'natural curiosity' to move them along. Motivation

(or 'wanting' as it is sometime described) can be achieved when using computer-aided learning by

impressing on the students how the course is increasing their learning, what it is adding to their

intellectual armoury, and how the course ties together. Furthermore it can be achieved by making the

course enjoyable. Multimedia elements can be included in Web pages, discussions can be opened up by

the Internet to bring in global audiences ( thus allowing students to share experiences with colleagues

elsewhere), and so on.

F. Resource-Based Learning (RBL)

Along with life-long learning, one of the most over-used expressions at the moment is that of

‘resource-based learning’ or ‘RBL’. Simply put, this focuses on the concept of giving the learner

greater access to resources (and thus more control of their learning experience). Because of the

multimedia and easy to access advantages of the Internet, the use of on-line teaching (especially with

the widespread popularity of the Web) has led many to advocate the policy of marrying the two

together. According to Gibbs et al (1994 xi ) RBL can be described as:

Enhancements to conventional courses

Lecture substitutes

13

Distance learning on campus; self-contained 'tutorials in print'

Self-pacing; alternatives to the lecture programme which allow the student to

progress at his or her own pace

Substitutes for specific learning activities e.g. computer simulations of experiments

Support for learning activities, e.g. study guides, field guides etc.

Hybrids. i.e. systems which emphasise class contact and learning resources in

varying degrees

In a sense, this report will look at nearly all of these as possible candidates for Internet delivery.

G. What Should One Use?

There is no simple answer to this, as it depends entirely on the teaching goals of the course, and the

technological capability of the host institution. As a guide, however, it can be looked on as a straight

forward trade-off: increased virtuality (i.e. more technically advanced uses of the Internet) means more

work required for setting up the course and insuring its success. For example, it is very easy and quick

to set up an e-mail list, but it is far more complicated to run a MUD (Multi-User Dungeon).

In summary, one could categorise as follows:

Virtual lite: Use of e-mail and discussion lists

Virtual medium: Discussion lists and on-line lecture notes delivered via the Web, and the use of

Computer-mediated Communication (CMC)

Virtual heavy: Above plus interactive Web tutorials designed specifically for the course and student

interaction (e.g. production of their own Web pages)

Virtual expert: Above plus virtual environments (e.g. MUDs and MOOs)

H. Is It Easy To Be Successful?

Again, the success of the course rests on several factors: motivation of the students; the use of scholarly

sound material; support, and so on. Motivation has already been discussed, and it is impossible to

advise on which material one should use as this requires subject-specific expertise (although good

advice on this can be found at the various Computers in Teaching Initiative [CTI] Centres). However,

when it comes to support, a category that is often disastrously overlooked, success rests on all of the

following:

* academic support

* administrative support

* technical support

14

* training

* equipment provision

* facilities provision (e.g. space)

* adequate delivery

* maintenance/security

Individual institutions will supply some of this, but in most cases the academic attempting to create online material has to rely on support from outside. Such bodies as the NetSkills project

(http://www.netskills.ac.uk/), with their on-line courses and regional workshops attempt to fulfil this

need but obviously they can only be of partial success (see also NetLearn directory of courses to teach

Internet skills at http://www.rgu.ac.uk/~sim/research/netlearn/callist.htm). In cases where any of the

above categories have been overlooked the success of the course could be greatly diminished.

Stuart Lee

i

Jackson, M., and Parker, S. 'Resource Based Learning and the Impact on Library and Information

Services' as part of the IMPEL2 project (http://ilm.unn.ac.uk/impel/rblrng.htm). For more information

see the excellent on-line forum at the DeLiberations Site (DeLiberations on Teaching and Learning in

Higher Education - http://www.lgu.ac.uk/deliberations/home.html). See also See Fraser, M. 'Dearing

and IT: Some Reflections' Computers & Texts 15

(http://info.ox.ac.uk/ctitext/publish/comtxt/ct15/fraser.html).

ii

See University of Central Lancashire's list of links related to the Dearing and Kennedy reports (and

subsequent responses) at http://www.uclan.ac.uk/other/uso/plan/dearing.htm or UCISA's page at

http://www.ucisa.ac.uk/docs/ll.htm.

iii

The Arts and Humanities Data Service response to ‘Connecting the Learning Society’ is available on

the AHDS web pages at http://ahds.ac.uk/public/grid6.html.

iv

The article appeared as 'Virtual-Classes Trend Alarms Professors', Chronicle of Higher Education

(June 19, 1998).

v

Gromov, G. The Roads and Crossroads of the Internet’s History

(http://www.internetvalley.com/intval.html), see also the Internet Society’s pages

(http://www.isoc.org/).

vi

Somekh, B. ‘Designing Software to Maximise Learning’, ALT-J 4.3 (1996), pp. 4-16.

vii

Laurillard, D. Rethinking University Teaching (London, 1993).

viii

Tait, B. 'Constructive Internet Based Learning' Active Learning 7 (December, 1997) pp. 3-8.

ix

Oliver, M. and Conole, G. 'Evaluating Communication and Information Technologies: A Tookit for

Practitioners', Active Learning 8 (July, 1998), pp. 3-8. Part of a special issue on ‘C&IT: Learning

Outcomes Evaluated’. See also Oliver, M. 'A Framework for Evaluating the Use of Educational

Technology' (http://www.unl.ac.uk/latid/elt/report1.htm) part of the BP Evaluating Learning

Technologies Project.

x

See Laurillard D, (1994) ‘Multimedia and the Changing Experience of the Learner’ in Proceedings of

APITITE 94 Conference, pp. 19-24 (and a list of Laurillard’s presentations at

http://watt.open.ac.uk/OTD/diana.htm).

xi

Gibbs, G., Pollard, N., Farrell, J. Institutional Support for Resource Based Learning (Oxford Centre

15

for Staff Development, 1994). See also Jackson, M. and Parker, S. ' Resource Based Learning and the

Impact on Library and Information Services' (http://ilm.unn.ac.uk/impel/rblrng.htm).

16

Email Lists - Virtual Lite

A. Introduction

The sending and receiving of electronic mail, or e-mail, has become one of the most frequent

applications of the Internet. It has given its users a new way of communicating which partakes

somewhat of both the immediacy of a phone call and the opportunity for considered reflection possible

in a letter. E-mail makes it possible for students to stay in touch with their peers and with the teaching

staff where a loaded schedule may make this otherwise difficult. The figure of the lonely scholar, who

can become isolated through increasing specialization, or for more prosaic reasons of inadequate social

or language skills, is one to whom e-mail presents some interesting possibilities i . The next chapter will

explore the full range of computer-mediated communication tools available (CMC), but this chapter

will restrict itself to the pedagogical uses of e-mail.

B. Using Mailing Lists: Some Case Studies

Mailing lists are a form of email which allow the subscriber to communicate with all the other

subscribers in one go. Instead of posting a message to a person, a message is posted to the list address

and is distributed to all the members of the list. A couple of examples of how lists have been used in a

teaching environment can be used to demonstrate some of the issues. The two lists in question were set

up for quite different reasons and were administered in different ways. Both lists, however, show that

once any initial difficulties in using e-mail systems in general have been overcome, the list participants

can become fired with a great enthusiasm for the medium. Stokes and Stokes (1996), in their article

‘Pedagogy, Politics, Power ii ’ regard this enthusiasm as symptomatic of the way in which such means

of communication hold the potential to challenge traditional pedagogic relationships:

‘The genuinely transformative nature of cyberspace lies not with access but with the

potential for the production of knowledge and for new modes of collaboration and

communication that can subvert and invert established author-ity relations, allowing the

emergence of a democratising literacy’

The first example of this ‘democratising literacy’ is the list set up by Ruth Dickstein, a social sciences

subject librarian, and Kari Boyd McBride, a lecturer in women's studies at the university of Arizona.

Dickstein and McBride set up their list as part of a class in critical theory. The idea was to integrate the

use of the list closely with activities in the classroom and with the material covered by the set texts.

With this they not only hoped to encourage an on-going exchange between the class members, but

could steer this exchange through their own participation in the list. They would also be imparting

some of the transferable skills which their students would find useful to their future employment or

further studies. The list was a closed list, i.e. no-one from outside the class could subscribe. They

17

constrained the class to contribute to the discussion by making it a compulsory and graded part of the

programme that each student must submit at least one substantial posting to the list each week.

After some initial difficulties of a largely technical nature the list started to blossom, rapidly going well

beyond the required one contribution per week. In fact the sheer volume of traffic on the list meant that

students without easy access to their e-mail accounts felt daunted, when logging on, by the numbers of

unread messages which awaited them.

Using a list meant that, effectively, the class could continue outside of its allotted classroom hours.

‘Another student said that she liked the idea of the 'on-going' class that happened even at

weekends. While some might think that this would be oppressive, she said, it was

interesting because the listserv was an on-going conversation, not an ongoing lecture.’

(McBride and Dickstein, 1996 iii )

Exchanges on the list developed an identity for the participants which had a curious detachment from

their real persona

‘...enthusiasm about on-line conversations created some frustration about classroom

interaction. Students knew each other by name on the listserv, but had no idea who that person

was they'd had an exiting exchange with on-line the previous evening. They introduced

themselves in class ('Hi, I'm so-and-so and I wrote about such-and-such'), but once wasn't

enough-we needed to repeat the introductions many times during the semester.’

(McBride and Dickstein, 1996)

In some ways McBride and Dickstein's contributions to the list were subject to a similar effacement.

The whole class took responsibility for encouraging each other's efforts and guiding lines of thought

with suggestions taken from their individual areas of interest. The traditional authority of the lecturer

became dispersed as the class began to author it's own discourse: ‘one student said ‘We have developed

class consciousness’’. All the students felt, by the end of the semester, that they had participated in an

intense and powerful learning experience.

‘…the mechanics of internet response do not require turn taking. From the oral side, it is as if

everyone who is interested in talking can all jump in at once, but still their individual voices

can be clearly heard. From the written side, it is as if someone had started writing a piece, but,

before he/she gets too far, people are there magically in print to add to, correct, challenge, or

extend the piece.’

(Shank, 1996 iv )

18

A somewhat different example is the list set up by Stokes and Brannigan, as mentioned in the article by

Peter and William Stokes (noted above). The list grew out of an informal e-mail exchange and was set

up as a collaborative writing project. The list membership rapidly grew from he original three to some

seventeen. As in the McBride and Dickstein case, Stokes notes the democratising effect of mailing

lists:

‘Even those who might be reluctant to claim a turn to speak in an oral conversation, were

free to construct and send their messages. All of the expectations of prompt, spontaneous

response in oral conversation are transformed. The participant, as writer, has the privilege

of choosing the time, length and deliberateness...of a message.’

(Stokes and Stokes, 1996)

It was an open list and contributions were entirely voluntary. Stokes notes that, again, the nature of the

medium was effectively altering the traditional teacher-student relationship in which

‘...teachers speak and students listen, books by authors are assigned and students read.

When students do speak or write, their actions are subject to immediate evaluation for their

correctness, accuracy, cogency and thoroughness in relation to some criteria established by

the teachers.’

(Stokes and Stokes, 1996)

On the list, students became actively involved in ‘the production of knowledge’ rather than just being

its passive recipients. Dickstein and McBride note the same effect and see the email list as going

towards ‘realizing postmodern epistemologies which assume that knowledge is not static or preexistent

but, rather, is always situated, always partial, always dynamic’.

The use of an open list can have drawbacks as well as advantages. A voluntary list in a classroom

situation can lead to a less than universal uptake in the use of the list by the students who are intended

to be its primary targets. In his article ‘Enoch in Cyberspace’ James R. Davila says of the open list set

up by him for the teaching of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha that:

‘an open international discussion group is a far better introduction to cyberspace … than a

closed list restricted to the class, even though the experience can be a baptism of fire for

some of them. Each student posted a summary of his or her class essay onto the list, but

otherwise the registered students were fairly quiet.’ v

The reason for this reserve may be, as noted by Bill Downey in a message to the Deliberations email

list that:

19

‘mailing lists are not perceived as a conversational medium. You are writing for a critical

audience and cannot write as freely as you can speak. People are reticent about contributing

anything not sufficiently ‘worthy’ and fearful of having their contributions

attacked.’(Downey vi )

Following on from their initial use of the Listserv Dickstein and McBride repeated the exercise the

following year. They expanded on the original small class and tried to run similar lists for three groups

of forty to fifty students each. This brought to light another potential problem where the list owners

intend to use the list actively to guide students: ‘the volume of email quickly became overwhelming for

all involved. The librarian, who also was on two other class lists, had to sign off periodically just to

survive.’ (Dickstein and McBride, 1998 vii ) Such a volume of messages meant that, instead of the close

supervision of postings which had taken place the previous year, the two were forced to be a little more

superficial in their monitoring of the student’s mail. This led to what the authors called ‘a pedagogical

disaster’ where one student misinterpreted an assignment and, the instructor and librarian having

missed the error, led some of the other students into the same mistake:

‘Within a day, most of the other students in that section had followed the lead lemming

over the cliff into academic suicide…The day of the lemmings proved a significant lesson

about the importance of staying engaged with the list discussions. When the phenomenon

began to emerge a second time…the librarian and the instructor were prepared… [and able

to] use the student’s misunderstanding as an opportunity to restate and elaborate on the

assignment for the rest of the class.’ (Dickstein and McBride, 1998)

Stokes (1996) noted the asynchronous nature of list exchanges and highlights it as a possible problem

as multiple subjects of conversation lead to an ever more complex list structure. The benefits of a clear

subject line in postings is obvious here.

‘we were compelled to read 'fractally'. The reader and responding writer needed to

recognize the order within the seeming disorder of the temporally contiguous but noncontingent messages. Yet, the months long exchange succeeded in remaining a complexly

coherent conversation with multiple participants.’

One way of mitigating this confusion, to some extent, is the use of threading within the list. Some

systems, such as Hypermail viii , allow the messages in a list to be organized by subject line. The

hierarchical arrangement of messages into related threads makes following multiple conversations

within a list a more intuitive process.

‘…discussion lists operating under listserv or listproc software provide the capability of

accessing discussion material as selected by date, person, subject matter, or any of the

above. As a consequence, this multiform availability of information within the overall

20

multilogue form facilitates the hybridisation of information, since we are capable of

operating within a series of simultaneous and parallel sets of discussion in the typical

multilogues setting as a matter of course.’

(Shank et al, 1996)

Such threading can also be seen extensively in newsgroups, where the paradigm is more of a noticeboard where people post messages rather than an asynchronous conversation. Newsgroups work by

having you go and fetch the messages or threads you are interested in rather than sending them to you.

Many public newsgroups have an established ‘community’ of posters. Often a list of Frequently Asked

Questions, or FAQ, is maintained to discourage repeated postings of the same low level queries.

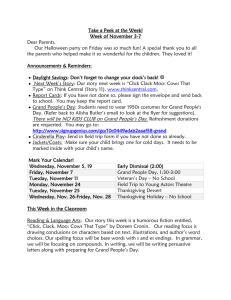

Fig 1. An Example of threading in action (taken from the Virtual Seminars project)

The demand for e-mail in HE institutions is growing rapidly as a new generation of computer literate

students come up through the secondary education system. At Oxford Brookes University, at the

beginning of the 95/96 academic year, 20% of newly enrolled students made enquiries about e-mail

accounts. By the start of 96/97 the figure had risen to over 90% and there have been further, if less

dramatic, rises in 97/98. There is no doubt, as the JISC Assist report Collaborative Working notes:

‘Computer mediated collaboration is increasing. At Loughborough University, for

example, email communication exceeds paper communication by 2:1’

21

(Wallace ix )

C. Creating A List

Institutions without a mail server can take advantage of one of the new, free, web based email services

such as Hotmail (www.hotmail.com). Students can register for an account and perform all the

functions of conventional email, such as dealing with attachments, subscribing to lists and so on,

through a web interface. The increasing use of e-mail means that mailing lists in a classroom situation

fast becoming an accessible form of teaching.

There are several ways to get a list set up. The Mailbase group x will set lists up with no charge for

academic purposes, subject to the approval of short description of the list's purpose submitted to them.

Another way is to have the systems people at the institution set up a Majordomo suite of list handling

programs on the local mail server xi . The Majordomo programs are freeware and mean that unlimited

numbers of lists can be set up within the institution. These lists will not be restricted in their

membership to just that institution, unless they are deliberately set up to be so, but can be accessed by

anyone having the relevant address.

D. Tips for a Successful List

Apart from these purely technical points, there are some things which should be considered when

setting up a list to ensure that it is effective in achieving its purpose:

Identify your community

Is the list to be open or restricted? Is the list open ended or does it have definite goals? If the latter,

what constitutes the list fulfilling its goals? What happens then? Establish guidelines for postings

perhaps including Conventions for subject lines (such as the date of posting) What constitutes on or off

topic?

Publicize your list

Unless the list is set up for a discrete group (as in the McBride/Dickstein cases), you will want to

attract a membership for the list. Publicity, such as posting to related lists or newsgroups, inclusion of

the list address in a business card or letterhead, and word of mouth, should be done at every

opportunity both when the list is set up and at regular intervals once the list is up and running. If you

are using a Mailbase list there is also the Mailbase list of new lists to which you can submit

information about your list.

Stimulate discussion

Unless you are making contributions to the list a compulsory part of a programme of study, you should

take some trouble over encouraging contributions from your members. Plant seed messages and

encourage the active members by making relevant responses to their posting wherever possible. You

22

may want to make it a list policy that new members introduce themselves and give a brief description

of their areas of interest and their reasons for joining the list.

The weight of anecdotal evidence suggests that a substantial percentage of list members will not be

active in the list discussions. The 'lurker' who subscribes to the list and perhaps reads all the postings,

but never makes a contribution, will be a familiar figure to anyone who manages a list of any size.

Even the lurker, however, will derive benefit from their membership of the list. They will learn, if only

in the more traditional sense of a passive and unidirectional acquisition of knowledge rather than being

actively engaged in the production of knowledge. Those who take the trouble to contribute to the list

will find themselves involved in what Stokes (1996) termed ‘the pedagogies of possibility’.

Chris Stephens

i

The best list of discussion lists available is the one maintained by Diane Kovacs at

http://www.n2h2.com/KOVACS/

ii

Stokes, P. and Stokes, W. ‘Pedagogy, Politics, Power.’ Computers and Texts 13 (1996), pp. 4-7.

iii

McBride, K. Dickstein, R. ‘Making Connections with a Listserv.’ Computers and Texts 12 (1996),

pp. 7 - 11. See also Dickstein and McBride (1998) and Ruth Dickstein’s page http://dizzy.library.arizona.edu/users/dickstei/homepg.htm.

iv

Shank, G and Cunningham, D. ‘Mediated Phosphor Dots: Towards a Post-Cartesian Model of

Computer-Mediated Communication via the Semiotic Superhighway.’ in Philosophical Perspectives

on Computer-Mediated Communication (ed.) Charles Ess. Vol. 1. (New York, 1996) pp. 27-45.

v

Davila, J. R. ‘Enoch in Cyberspace: The Internet meets the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha’

Computers and Texts 15 (1997), pp. 8-10.

vi

Deliberations list is an Elib project, available: http://www.lgu.ac.uk/deliberations/. Downey’s

message was posted on 10th October 1998.

vii

Dickstein, R and McBride, K.B. ‘Listserv Lemmings and Fly-brarians on the Wall: A librarianInstructor Team Taming the Cyberbeast in the Large Classroom’ College and Research Libraries 59

(1998), pp. 10-17.

viii

Hypermail information -http://tecfasun1.unige.ch/guides/hypermail.html.

ix

Wallace, D. Collaborative Working JISC Assist Report (1998, available at:

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/pub98/assist2.html).

x

See http://www.mailbase.ac.uk.

xi

Majordomo information -http://www.public.iastate.edu/~majordomo/faq.html.

23

Computer Mediated Communication (CMC)

A. Introduction

The focus within this section of the guide is on the use of asynchronous CMC systems for supporting

group learning. That is, systems that allow groups to interact over time as well as over geographical

location. This is a different type of interaction to that supported by videoconference systems, which

allow people to be geographically dispersed, but require them to be present at the same time. E-mail,

for example, is a simple form of CMC and its use to support learning has been covered in the previous

chapter. Other examples of asynchronous computer conferencing systems are Lotus Notes/Domino,

FirstClass, TopClass and WebBoard. The University of Bangor has produced a comprehensive list of

CMC systems, including links to demonstrations and downloads of trial software.

Computer Managed Learning environments go a step further bringing support for other educational

processes into play such as assessment, student tracking and so on e.g. TopClass/WebCT, Lotus’

Learning Space.

The main difference between e-mail and a CMC system is that the structure of a discussion is

maintained in a coherent model without the user needing to do anything, making it suited to groupbased interactions. With e-mail, messages arrive chronologically and are only grouped if the user takes

to time to put related messages into folders. Even where threading is supported by an e-mail system,

discussion threads are often broken if the subject line is changed.

The main thing is not so much the specific system used, but that, given the potentials and limitations of

this type of internet application, how do lecturers ensure that they use it in a pedagogically effective

way. The following sections highlight the potentials and limitations of CMC; introduce some models

for using CMC; describe examples of use of CMC at Undergraduate and Postgraduate level; present

guidelines for effective implementation/integration of CMC to support teaching and learning; and

finish with mention of broader computer managed learning environments that have CMC as one

element.

The final Bibliography section contains links to a number of CMC systems as well as other web sites

and readings relevant to CMC and the associated pedagogical issues.

B. Potentials

CMC systems allow learners to interact with one another over time. This time independence allows

students to fit their on-line discussions around their other commitments and responsibilities. Different

work patterns can be supported whilst still maintaining a feeling of community amongst the students

and staff participating in the course. This is particularly pertinent where students are distributed around

the world and potentially in different time-zones.

24

These systems retain a textual, permanent record of interactions, indicating to a user as they rejoin a

discussion which comments have been added since the last time they were there. This is particularly

useful if participants have not been able to join in due to, for example, working away, other

commitments, or illness. It has been found that CMC environments are particularly useful for students

for whom English is not their first language. They can take the time to check their understanding

without ‘missing’ any comments as they may do in a face to face situation. They can also take their

time to compose their replies without being under pressure as in a face to face situation.

Learning in a CMC environment can lead to deeper processing of material because time for reflection

is allowed. Due to the textual record that is kept, people can refer back to things that were discussed

earlier, and take their time to respond, perhaps researching their answer before putting it on-line.

CMC systems provide opportunities for groupwork that would not otherwise exist e.g. for distance

learning students on programmes where all support is done remotely via mail, e-mail or phone/FAX.

Where in a more traditional model of support learners may only be able to communicate with their

tutor about the subject material and their assignments, use of CMC can allow peer discussion to take

place also.

The use of CMC systems to support distance learners has clear advantages of flexibility over the time

and place of study (McConnell, 1994; Laurillard, 1994; and O’Malley, 1989 i ). Thus far it has received

little attention from researchers and teachers in terms of its use for on-campus students. The flexibility

over time offered by CMC can be extremely useful for on-campus students, particularly when they are

engaged in groupwork. Getting groups to meet is notoriously difficult for staff as well as student

groups. This is compounded all the more if these groups then have to meet with other groups, as is the

case in the illustration used later.

C. Limitations

CMC is of course not a panacea. Since it is largely a text-based medium (although increasingly new

systems support multimedia), there is a lack of expressive richness since no non-verbal cues exist to

enhance what is being said, and in particular the way that something is being said. Comments can

often appear more critical than intended and great care is needed when this medium is used to give

feedback about students work.

The flexibility over time, whilst it has great benefit, can also be a problem for participants. It may be

days, depending on the level of activity within a conference, before someone replies to a question.

Decision making can be difficult on-line, again due to flexibility over time and the notion that everyone

can have their say in this environment. Strong chairing is needed to come to a conclusion in an on-line

environment, although some systems support decision making with features such as voting.

25

Using CMC systems requires access to a computer and the internet, and arguably participants require a

certain level of technical competence to overcome any difficulties that arise from accessing the CMC

environment.

The style of on-line communication has to be developed by the group. Different groups develop

different norms and styles as they would in a face to face situation, but on-line communication is

different in that it is not formal letter writing and neither is it a postcard. Also the level of discourse

may be different for different areas of a CMC system. For example, you would not expect students to

communicate in a ‘virtual café’ in the same way that they would in an on-line tutorial. Sometimes

these levels of discourse can be at odds as people continue in an informal way in a more formal area.

One way to address this need to learn on-line behaviour is to use familiar face-to-face equivalents to

give strong clues to participants about what is expected of them and the tutor in the on-line

environment.

D. Models of Use

A number of models have been used at Lancaster University to clarify the purpose and participants role

in the on-line environment. The model below gives an overview of these models in increasing order of

participant interaction.

Models of Participation

Notice Board

Question & Answer

Levels of

learner

engagement

Electronic Debate

CSCL

Electronic Seminars

Global Links

Collaborative

Learning

Fig 1: Models of Participation (Steeples, 1998 ii )

Noticeboard

This is the most simple use of CMC, where participants only have read access to the area and tutor’s

can post up messages. It has the advantage that participants can get used to moving around the CMC

26

environment using a subset of the systems functionality. It can be seen as a gentle introduction for

both staff and students to a system, since the roles and responsibilities of each is clear.

Question and Answer

This model is similar to that of a FAQ. This can be introduced to students as a route by which they can

ask for help from the tutor and/or from each other. Typically this is a problem oriented dialogue, and

has the benefit that tutors can see this from the questions that are asked what students real problems are

with the course. These issues can then be addressed in class or tutorial time if a general

misunderstanding has occurred. They may also form a useful resource for future cohorts of students,

perhaps with the tutor pulling out the main points to be carried forward. It also provides a useful tool

to tutors when redesigning the following year’s course.

Electronic Debate

This takes the metaphor of the formal debate with a proposer for and against a motion to set the scene,

followed by a general debate where all students are encouraged to participate. This model was used in

a debate about Environment or Development for India at Lancaster University involving staff and

students from the departments of Economics and Geography

(http://www.lancs.ac.uk/users/edres/research/NetAcad/home.html).

Electronic Seminar

This discursive model can be used in a variety of ways and lends itself well to situations where students

are all working through course material at a similar pace, for example, a typical on-campus

undergraduate course. It is not so well suited to situations, e.g. as with some distance learning

programmes, where students can be at a wide range of different points in the study material and so

focussed discussion is problematic.

Different roles can be adopted here either by design or left to emerge. So, for example a tutor may

decide that participants must each take a turn to initiate a seminar session (be the Leader), or it may be

left to whoever is on-line first to initiate discussion about a particular reading. One documented

example where this approach has been used successfully in the Department of Music at Glasgow.

Collaborative Learning (or learning to collaborate)

CMC allows participants to work in ways that may otherwise be impossible due to constraints of time

or location. It is difficult to imagine a student body from different continents, collaborating on the

design of a web page for example, in a non-CMC supported distance learning course. Use of CMC

allows design discussions and decisions to be made as a group, over time.

Role play is another metaphor that can be supported in a CMC environment and the Undergraduate

second year Law example given below details such an approach.

27

It is also possible to encourage students to use the CMC environment to coordinate tasks - breaking

down a project into discrete tasks and using the CMC environment as a project management tool.

Students can also be encouraged to collaborate on tasks - actually using the medium to achieve a shared

goal. The second Undergraduate example provides an example of this approach.

Global Links

CMC offers the potential for 'visiting speakers' without the need to have the person physically present.

For example it can be a way of Involving authors of papers who may be based in other countries and

unlikely in a traditional course, to be able to attend and debate their writing with students. Since CMC

alleviates the need for them to travel and allows them to participate at a time and a place convenient to

them, students can be exposed to global resources and people that would otherwise be unavailable. For

example, in the debate model mentioned earlier, participants from India could be invited to join the

debate and offer their views.

E. Examples of use

Undergraduate

Using CMC to support team-based negotiations

In the Law department at Lancaster University, a second year course, Common Law of Obligations,

has harnessed CMC to develop independent student learning. The essential feature of the learning