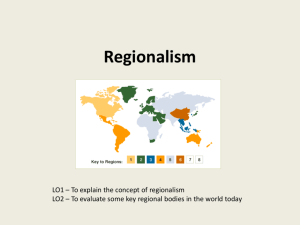

“Globalisation and Economic Regionalism: A Survey and Critique of the Literature”

advertisement