Strategic Management Journal

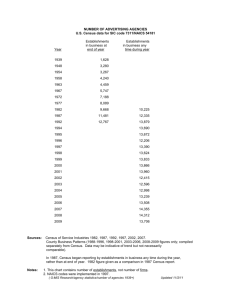

advertisement