Refugees’ reception and settlement in Britain Lynnette Kelly and Danièle Joly

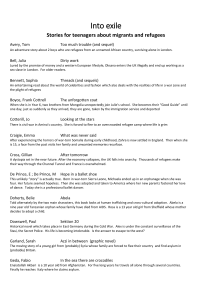

advertisement