Loyalty Insights

Developing a root cause capability

By Rob Markey and Fred Reichheld

Fred Reichheld and Rob Markey are authors of the bestseller The Ultimate

Question 2.0: How Net Promoter Companies Thrive in a Customer-Driven World.

Markey is a partner and director in Bain & Company’s New York office and

leads the firm’s Global Customer Strategy and Marketing practice. Reichheld

is a Fellow at Bain & Company. He is the bestselling author of three other

books on loyalty published by Harvard Business Review Press, including The

Loyalty Effect, Loyalty Rules! and The Ultimate Question, as well as numerous

articles published in Harvard Business Review.

Copyright © 2012 Bain & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Developing a root cause capability

Airlines regularly survey flyers, asking how likely respondents would be to recommend each of the carriers they

use to friends and colleagues. They also probe the reasons for different ratings. Of course, many passengers give

certain airlines poor ratings because they believe those airlines perform significantly worse than competitors in

on-time performance—more delays, more cancellations and so on. But in many cases, flight data shows that the

gap is far less than customers seem to think. What’s really going on?

A large insurance company was struggling with persistently low Net Promoter® scores (NPS)1 among customers

who had recently filed claims. Trying to identify the reasons, the company heard a common theme: Claims agents

weren’t demonstrating sufficient empathy. Typical responses included “They made me feel like a criminal” and “I

had to prove everything over and over.” Concerned, the insurer launched a series of training initiatives to improve

its agents’ listening skills and help them learn to show empathy. But nothing seemed to help—customers were

still unhappy. Why were the efforts fruitless?

Virtually every large enterprise devotes significant

time and resources to surveying its customers about

their attitudes, behaviors and intentions regarding the

company’s products or services. Usually it’s the marketing department that sponsors these surveys, and

usually the surveys contain endless numbers of questions. There’s a reason for the length, of course: The

goal is to pinpoint exactly what customers most like

and most dislike.

The Net Promoter system’s process takes a different

approach. NPS companies typically ask their customers

just two questions: How likely would you be to recommend this company [or product] to friends and colleagues?

and What is the primary reason for your rating? Some of

these surveys, like the airline one described above, are

“top down”—anonymous studies that compare ratings

among competitors. Others, like the insurance company’s, are “bottom up,” meaning internal surveys

of a company’s own customers, often conducted right

after a transaction. (To learn more about the difference, see www.netpromotersystem.com/top-bottom.)

In both cases, the questionnaire is short so response

rates are usually high. The company learns exactly

what’s on customers’ minds, expressed in their own

words. The processes generate a steady stream of data

that frontline supervisors and employees can use to

improve their performance.

That’s why the typical hotel questionnaire, for instance,

asks about the reception desk, the bell captain, the

concierge, the air conditioning, the lighting, the pillows,

the bed, the minibar, the turn-down service, the shower

and on and on, usually 30 or 40 individual items in

all. And what happens? Most customers just toss the

card back on the dresser, never filling it out, and the

hotel never learns what is on those customers’ minds.

As for the minority who do fill out the cards, respondents find themselves limited to the categories established by the hotel’s survey designers. Suppose that

what you really value is the hotel’s location and what

you really hate is the noise of the garbage trucks out

back at six AM, and neither of those items appears on

the long list of questions? There isn’t a survey in the

world—at least not one that a reasonable person would

answer—that can cover every conceivable reason for a

customer’s reactions to a product or service.

But a Net Promoter system poses a challenge to its

practitioners. Customers can always articulate what’s

bothering them or what they most like about a company.

But they don’t always know the full story behind their

own feelings. So companies can rarely stop with customers’ expressed comments. The insurer, for instance,

heard the complaints—lack of empathy—and quickly

decided that it should help agents show more empathy.

But things didn’t improve.

1

Developing a root cause capability

This is where root cause analysis enters the picture.

sible for shaping the customer’s experience almost

always results in better, more enduring solutions, whether

those teams consist of call center agents, web designers, product developers, pricing managers or sales

directors. Digging for root causes is a skill to be developed throughout the organization, not reserved just for

specialists in a central department.

The five whys

Root cause analysis in business goes back to the Total

Quality movement and ultimately to the Toyota Production System. Toyota—and, later, many other companies—trained production analysts to ask why a defect

appeared and to keep asking why until they had identified a root cause. It wasn’t enough to note that a

machined part was loose because the hole it fit into

was too big. Why had the operator drilled the wrong

size hole? Had he chosen the wrong bit, and if so, why?

Was the bit stored in the wrong bin? Was it mislabeled?

If so, why? The process of asking at least five whys

gave companies the ability to attack not just the symptoms

of poor quality, such as a loose part, but the underlying root cause —the core reason behind what happened.

Look once more at the two real-world examples at the

beginning of this article.

The unhappy passengers. A team at one airline that

saw a discrepancy between the company’s actual ontime performance and customer perceptions began

their search for the root cause by studying customers’

responses. Among the many customers upset about

travel delays and cancellations, some felt they didn’t

receive appropriate compensation. An obvious first response for any airline is, maybe we should offer more

compensation and improve our on-time performance.

But both solutions would cost millions of dollars. Better on-time performance, for instance, requires spare

planes, backup crews, extra mechanics on duty and

so on.

It’s much the same with customer feedback. If a customer

says that the product’s price is too high, for instance,

that’s not the end point; it’s merely the starting point

for further investigation. Why does she feel that way?

Is it because she doesn’t make use of the full set of

benefits the product offers? Is it because the most important benefits are buried in a sea of other, less valuable features? Is it because the company has sold the

wrong product to this particular customer? If a company ends its research with the customer’s statement,

“the price is too high,” it essentially has only two choices,

neither one satisfactory. It can lower the price to make

the customer happy, hurting its margin. Or it can keep

the price where it is and risk driving the customer away.

Asking the five whys leads to a larger set of possible

solutions. It also helps a company focus on solutions

that will be more likely to influence customers’ subsequent behavior and attitudes.

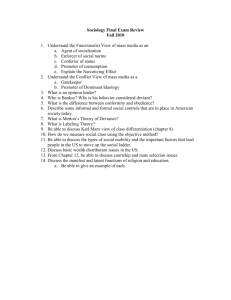

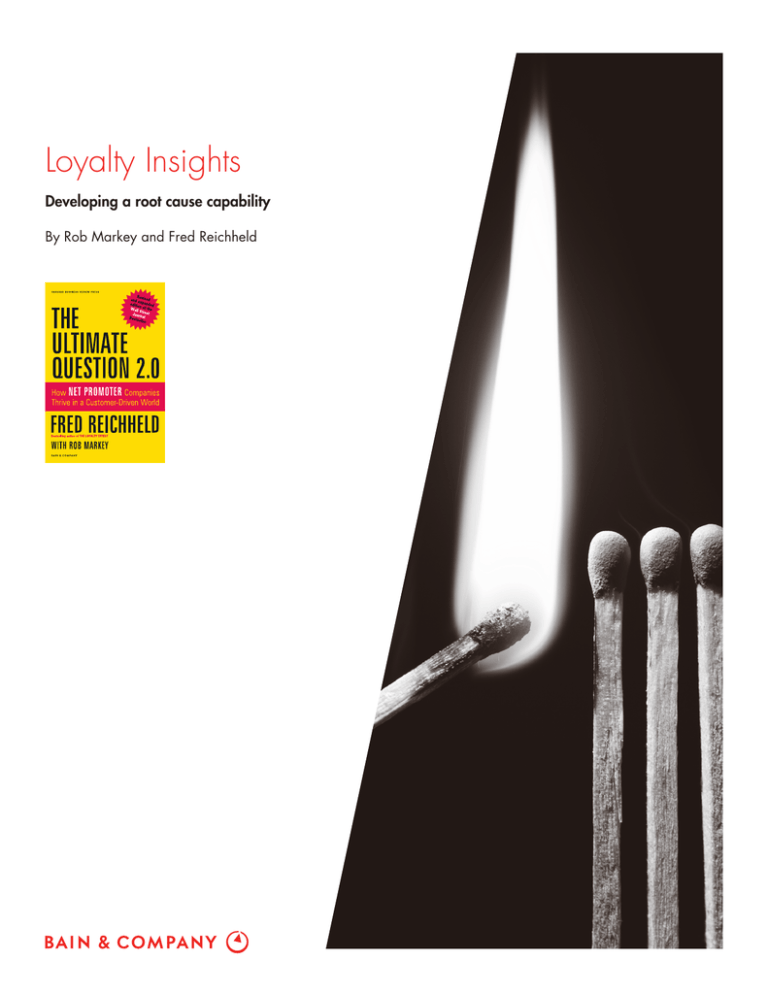

Closer analysis, however, yielded different insights. How

the airline handled delays seemed more important

than the delay itself (see figure). In fact, delayed passengers mostly fell into one of two groups: those who

felt that the airline’s communication about the delay had

been terrific and those who thought it was terrible.

Passengers who thought the airline had communicated

well gave it far higher scores than those who did not.

In fact, the scores from passengers who experienced

long delays but good communication were about the

same as scores from passengers who experienced only

minor delays, but thought the communication had

been lousy.

And while it’s tempting to hand off the job of digging

for root causes to specialists at corporate headquarters—

after all, they have the experience, skills and time available to do the job well—that’s usually not the best

solution. Engaging the teams that are directly respon-

The team could now investigate each group further.

Why did some people believe that communication

had been so good? It turned out that someone in au-

2

Developing a root cause capability

thority, usually the pilot, had addressed them clearly

and explicitly about what he or she knew and had shown

empathy with the passengers’ plight. Asking why that

didn’t happen all the time, the airline found that its

procedures were poorly defined: No one was quite

sure who was supposed to address the passengers.

Some pilots took the initiative to do so, others did not.

Moreover, pilots had differing levels of communications skills. Some made passengers feel a lot better

and others did not.

be perceived as lying—but as a result they waited for

“just five more minutes,” over and over. Unfortunately,

their good intentions resulted in prolonged silence

that contributed to passenger anger.

As for the group that felt communication had been

poor, many respondents said they had been given conflicting information, and thus believed that someone

had lied to them. Again, the airline’s team asked why.

They found that gate agents and other employees were

often using different and uncoordinated computer systems, which provided different information.

The unhappy callers. The story was similar at the

insurance company. Training the claims agents in

empathy and listening skills made some difference—

but not much. The reason: a set of policies and procedures that undermined even the most empathetic agents.

For example, the company required customers to fill

out a lot of paperwork. It required them to sign claims

requests in front of a notary. And since the company’s

systems did not provide each representative with the

claimant’s full story, reps were forced to ask for the

Once the “why?” questions were asked and answered,

the airline could take corrective actions, including

synchronizing information systems, clarifying communications procedures and training pilots in communications skills.

They also discovered that gate agents were reluctant

to give out incomplete information—they didn’t want to

Figure: The way a delay or cancellation is handled has a bigger impact on passengers than the event itself

What bothered you most about the DELAY?

What bothered you most about the CANCELLATION?

Net Promoter score

Net Promoter score

100%

80

30

80

21

46

60

40

100%

10

60

30

32

29

20

8

33

29

87

40

70

41

20

4

17

43

50

22

0

NPS

0

Delay

itself

Length of

delay

The way it

was handled

24%

11%

60%

NPS

Promoter

Passive

SM

SM

Sources: Survey BottomUp Delays, December 2011; Bain analysis

3

Cancellation

itself

Length of

delay

The way it

was handled

14%

33%

83%

Detractor

SM

Developing a root cause capability

the unsynchronized computer systems, for

instance, it had good reason to believe that

many passengers were indeed receiving conflicting information.

same information on every call, making customers

feel that they were being interrogated. Why were the

systems so limited? Well, rapid recall of notes from a

prior call would require a system upgrade, and the

company had never believed such an upgrade was

worth the expense.

3. Proposing actions. At this point the team can

assign a value to addressing each root cause.

What would fixing this problem cost? What

would it be worth? That leads to a list of proposed actions.

These root causes—which implicitly identified a set of

potential solutions—didn’t appear until the company

asked a series of “why?” questions.

Systematic root cause identification:

Four steps

4. Institutionalizing the feedback. The team then

loops back to key individuals in the company,

putting a feedback mechanism in place to ensure consistent attention to root causes. The

airline, for instance, created a measurement

system that gave employees faster feedback on

their adherence to best-practice behaviors, along

with direct feedback on what customers were

saying through the Net Promoter surveys.

Over time, leading Net Promoter companies have

developed procedures that embed root cause analysis

deep into their operations and processes. The procedures typically follow a four-step sequence.

1.

2.

1

Identifying most likely potential causes from

feedback data. Customer responses indicate

proximate causes of their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with your products or services.

Company employees can add their insights

into possible root causes, essentially creating

a list of hypotheses about what lies behind the

responses. The team can then rank-order the

list by likely importance.

The development of this capability—the root cause

discipline—is a key part of creating a powerful Net

Promoter system. It takes time and resources, but the

payoff is substantial. It enables a company not just to

hear the voice of the customer, but also to push deep into

its internal operations to learn exactly where it is doing

things right and where it is doing things wrong. The

company thus learns why it creates promoters among

some customers and detractors among others, and it

can take action to increase the former and decrease the

latter. That ability lies at the very heart of the true customer-centric enterprise.

Asking the “why?” questions. Team members

then begin pursuing the five whys for the topranked causes, thus deepening and enriching

their list of hypotheses. They assemble operational data that will help them test and validate

possible causes. When the airline uncovered

Net Promoter® and NPS® are registered trademarks of Bain & Company, Inc., Fred Reichheld and Satmetrix Systems, Inc.

4

Shared Ambit ion, True Results

Bain & Company is the management consulting firm that the world’s business leaders come

to when they want results.

Bain advises clients on strategy, operations, technology, organization, private equity and mergers and acquisitions.

We develop practical, customized insights that clients act on and transfer skills that make change stick. Founded

in 1973, Bain has 48 offices in 31 countries, and our deep expertise and client roster cross every industry and

economic sector. Our clients have outperformed the stock market 4 to 1.

What sets us apart

We believe a consulting firm should be more than an adviser. So we put ourselves in our clients’ shoes, selling

outcomes, not projects. We align our incentives with our clients’ by linking our fees to their results and collaborate

to unlock the full potential of their business. Our Results Delivery® process builds our clients’ capabilities, and

our True North values mean we do the right thing for our clients, people and communities—always.

For more information, visit www.netpromotersystem.com

For more information about Bain & Company, visit www.bain.com