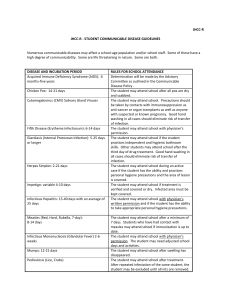

Communicable diseases: Epidemiology surveillance and response Definitions

advertisement

Communicable diseases: Epidemiology surveillance and response Definitions A communicable (or infectious) disease is one caused by transmission of a specific pathogenic agent to a susceptible host. Infectious agents may be transmitted to humans either: � directly, from other infected humans or animals, or � indirectly, through vectors, airborne particles or vehicles. Vectors are insects or other animals that carry the infectious agent from person to person. Vehicles are contaminated objects or elements of the environment (such as clothes, cutlery, water, milk, food, blood, plasma, parenteral solutions or surgical instruments). Contagious diseases are those that can be spread (contagious literally means “by touch”) between humans without an intervening vector or vehicle. Malaria is therefore a communicable but not a contagious disease, while measles and syphilis are both communicable and contagious. Some pathogens cause disease not only through infection but through the toxic effect of chemical compounds that these produce. For example, Staphylococcus aureus is a bacteria that can infect humans directly, but staphylococcal food poisoning is caused by ingestion of food contaminated with a toxin that the bacteria produces. 117 Role of epidemiology Epidemiology developed from the study of outbreaks of communicable disease and of the interaction between agents, hosts, vectors and reservoirs. The ability to describe the circumstances that tend to spark epidemics in human populations – war, migration, famine and natural disasters – has increased human ability to control the spread of communicable disease through surveillance, prevention, quarantine and treatment. The burden of communicable disease The estimated global burden of communicable diseases – dominated by HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria – is shown in Box 7.1. Emerging diseases such as viral haemorrhagic fevers, new variant Creutzfeld-Jakob disease and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), as well as reemerging diseases including diphtheria, yellow fever, anthrax, plague, dengue and influenza place a large and unpredictable burden on health systems, particularly in low-income countries. Threats to human security and health systems Communicable diseases pose an acute threat to individual health and have the potential to threaten collective human security. While low-income countries continue to deal with the problems of communicable diseases, deaths due to chronic diseases are rapidly increasing, especially in urban settings . Although high-income countries have proportionally less communicable disease mortality, these countries still bear the costs of high morbidity from certain communicable diseases. For example, in high-income countries, upper respiratory tract infections cause significant mortality only at the extremes of age (in children and elderly people). However, the associated morbidity is substantial, and affects all age-groups Using epidemiological methods to investigate and control communicable disease is still a challenge for the health profession. Investigation must be done quickly and often with limited resources. The consequences of a successful investigation are rewarding, but failure to act effectively can be damaging. In the AIDS pandemic, 25 years of pidemiological studies have helped to characterize the agent, modes of transmission and effective means of prevention. However, despite this knowledge, the estimated global prevalence of HIV in 2006 was 38.6 million cases, with 3 million deaths per year. Epidemic and endemic disease Epidemics Epidemics are defined as the occurrence of cases in excess of what is normally expected in a community or region. When describing an epidemic, the time period, geographical region and particulars of the population in which the cases occur must be specified. The number of cases needed to define an epidemic varies according to the agent, the size, type and susceptibility of population exposed, and the time and place of occurrence. The identification of an epidemic also depends on the usual frequency of the disease in the area among the specified population during the same season of the year. A very small number of cases of a disease not previously recognized in an area, but associated in time and place, may be sufficient to constitute an epidemic. For example, the first report on the syndrome that became known as AIDS concerned only four cases of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in young homosexual men.3 Previously this disease had been seen only in patients with compromised immune systems. The rapid development of the epidemic of Kaposi sarcoma, another manifestation of AIDS, in New York is shown in Figure 7.3: 2 cases occurred in 1977 and 1978 and by 1982 there were 88 cases. 4 The dynamic of an epidemic is determined by the characteristics of its agent and its pattern of transmission, and by the susceptibility of its human hosts. The three main groups of pathogenic agents act very differently in this respect. A limited number of bacteria, viruses and parasites cause most epidemics, and a thorough understanding of their biology has improved specific prevention measures. Vaccines, the most effective means of preventing infectious diseases, have been developed so far only for some viral and bacterial diseases. If the attempt to make a malaria vaccine is successful, this will be the first vaccine for a parasitic disease. Vaccines work on both an individual basis, by preventing or attenuating clinical disease in a person exposed to the pathogen, and also on a population basis, by affecting herd immunity