Document 12706179

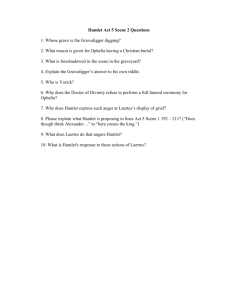

advertisement

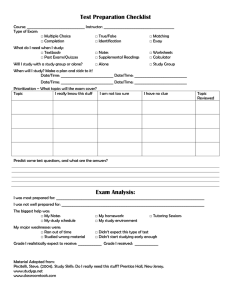

Curtain-raiser: Dr Faustus’s Study Shakespeare’s Stuff: The Properties of Early Modern Playing ‘Go to the Centaur, fetch our stuff from thence’ (The Comedy of Errors) ‘She [My wife] is…my household stuff, my field, my barn…’ (The Taming of the Shrew) ‘What stuff wilt have a kirtle made of?’ (I Henry IV) ‘In sooth I know not why I am so sad…what stuff tis made of…’ (Merchant) ‘Ambition should be made of sterner stuff’ (Julius Caesar) ‘Nature wants stuff to vie strange forms with fantasy…’ (Antony and Cleopatra) ‘This is the silliest stuff that ever I heard’ (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) ‘Youth’s a stuff will not endure’ (Twelfth Night) ‘We are such stuff as dreams are made on’ (Tempest) ‘Is not a comonty / A Christmas gambol or a tumbling trick?’ ‘No my lord, it is more pleasing stuff.’ ‘What, household stuff?’ ‘It is a kind of history’ (The Taming of the Shrew) Yet sit and see, Minding true things by what their mock’ries be. (Henry V, 4.0.52-3) Falstaff: Well, thou wilt be horribly chid tomorrow when thou comest to thy father. If thou love me, practise an answer. Hal: Do thou stand for my father and examine me upon the particulars of my life. Falstaff: Shall I? Content. This chair shall be my state, this dagger my sceptre and this cushion my crown. Hal: Thy state is taken for a joint-stool, thy golden sceptre for a leaden dagger and thy precious rich crown for a pitiful bald crown. I Henry IV, 2.4.364-371 x x x x Inventory of Properties belonging to the Admiral’s Men at the Rose, 1598 property, n. Brit. /ˈprɒpəti/ , U.S. /ˈprɑpərdi/ Etymology: < Anglo-Norman properté, propertee, propertie, propretee, proprité, Anglo-Norman and Middle French propreté (c1225 in Old French, also as propritei ), variants (probably after propre proper adj.) of proprieté propriety n. Compare Middle French, French propreté decent dress and manners (1538), neatness (1671) < propre proper adj. + -té -ty suffix1. †2. The quality of being proper or appropriate; fitness, fittingness, suitability; the proper use or sense of words. Cf. propriety n. 5b, 6. Obs. 3.†a. Something belonging to a thing; an appurtenance; an adjunct. Obs. 5. Theatre and Film. Any portable object (now usually other than an article of costume) used in a play, film, etc., as required by the action; a prop. Chiefly in pl. Cf. prop n.6 a1450 Castle Perseverance 132 Þese parcell [read parcellys] in propyrtes we purpose us to playe Þis day seuenenyt. 1578 in A. Feuillerat Documents Office of Revels Queen Elizabeth (1908) 303 Furnished in this office with sondrey garmentes & properties. 1600 Shakespeare Midsummer Night's Dream i. ii. 98, I will draw a bill of properties, such as our play wants. 1629 P. Massinger Roman Actor iv. ii. sig. I, This cloake, and hat without Wearing a beard, or other propertie Will fit the person. 1748 Whitehall Evening Post No. 371, To be Sold very cheap, Cloaths, Scenes, Properties, clean, and in very good Order. Let us think for a moment about how performance in itself vivifies objects…Theatre transforms objects of whatever sort into signs simply by presenting them on stage, to an audience; in that context, an ordinary object which we might hardly glance at in ‘real’ life can become weighty with meaning and charged with emotion. It is in the nature of theatre to effect such transformations, since everything shown to an audience carries the promise of something behind or beyond itself…[T]he theatre routinely invests the objects it shows with more than they carry in themselves. Anthony Dawson, The Culture of Playgoing in Shakespeare’s England (CUP: 2001, pp. 137-38). ‘Things …, like persons, have social lives.’ Circulating ‘in different regimes of value in space and time’ and moving ‘through different hands, contexts, and uses,’ objects ‘accumulate[] … biographies’, ‘become weighty’ with life histories. Objects are ‘things in motion’ that follow ‘careers’ which start them off down specific paths – life journeys – that regularly (certainly, in theatre, inevitably) get interrupted, blocked, diverted, where diversion is always ‘a sign of creativity or crisis’. Thus, an object that begins life as a gift may be inherited, sold, lost, stolen, found, sacramentalised as a relic, copied, faked, commodified, each exchange marking a shift in value, but not every act of exchange supposing ‘a complete cultural sharing of assumptions’ about that value. For what is ‘priceless’– that is, beyond price – in one pair of hands may be ‘priceless’ – worthless – in another. Objects, in short, function as ‘incarnated signs’. They exhibit ‘semiotic virtuosity’. See Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (CUP, 1986), pp. 3-34. Peter Quince! There are things in this comedy of Pyramus and Thisbe that will never please. First, Pyramus must draw a sword to kill himself… the lion… moonlight… we must have a wall … Snug’s Lion’s Head in Brook’s Dream (1971) ‘I Pyramus am not Pyramus’ ‘he is not a lion…half his face must be seen through the lion’s neck…’ ‘leave a casement…open; and the moon may shine in at the casement’ ‘or else one must come in with a bush of thorns and a lantern and say he comes to disfigure or to present the person of Moonshine’; ‘Some man or other must present Wall’. Enter Ophelia distracted, playing on a lute, and her hair down, singing (SD, Q1 4.5.21) Laertes: Oh, heat dry up my brains…is’t possible a young maid’s wits /Should be as mortal as a poor man’s life? Ophelia: There’s rosemary: that’s for remembrance. Pray you, love, remember. And there is pansies: that’s for thoughts. Laertes: A document in madness – thoughts and remembrance fitted! Ophelia: There’s fennel for you, and columbines. There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me… (4.5.155-178) Hamlet Yorick Skulls (left: Andre Tchaikovsky’s) Gravedigger: Here’s a skull now. This skull has lain in the earth three-and-twenty year. Hamlet: Whose was it? Gravedigger: A whoreson mad fellow’s it was. Whose do you think it was? Hamlet: Nay, I know not. Gravedigger: A pestilence on him for a mad rogue – a poured a flagon of Rhenish on my head once! This same skull, sir, was Yorick’s skull, the King’s jester. Hamlet: This? Gravedigger: E’en that. Hamlet: Let me see. Alas, poor Yorick. I knew him, Horatio – a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy. He hath borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how abhored my imagination is! My gorge rises at it. Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft. Where be your gibes now, your gambols, your songs, your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one now to mock your own grinning? Quite chop-fallen? Now get you to my lady’s chamber and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favour she must come. Make her laugh at that. Prithee, Horatio, tell me one thing. Horatio: What’s that, my lord? Hamlet: Dost thou think Alexander looked o’this fashion i’th’earth? Horatio: E’en so, my lord. Hamlet: And smelt so? Pah! … To what base uses we may return, Horatio! Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander till a find it stopping a bung-hole? … Imperial Caesar, dead and turned to clay, / Might stop a hole to keep the wind away. / O, that that earth which kept the world in awe / Should patch a wall t’expel the winter’s flaw! But soft, but soft; aside. [Enter Funeral]