EN2133 UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK Summer Examinations 2015/16

advertisement

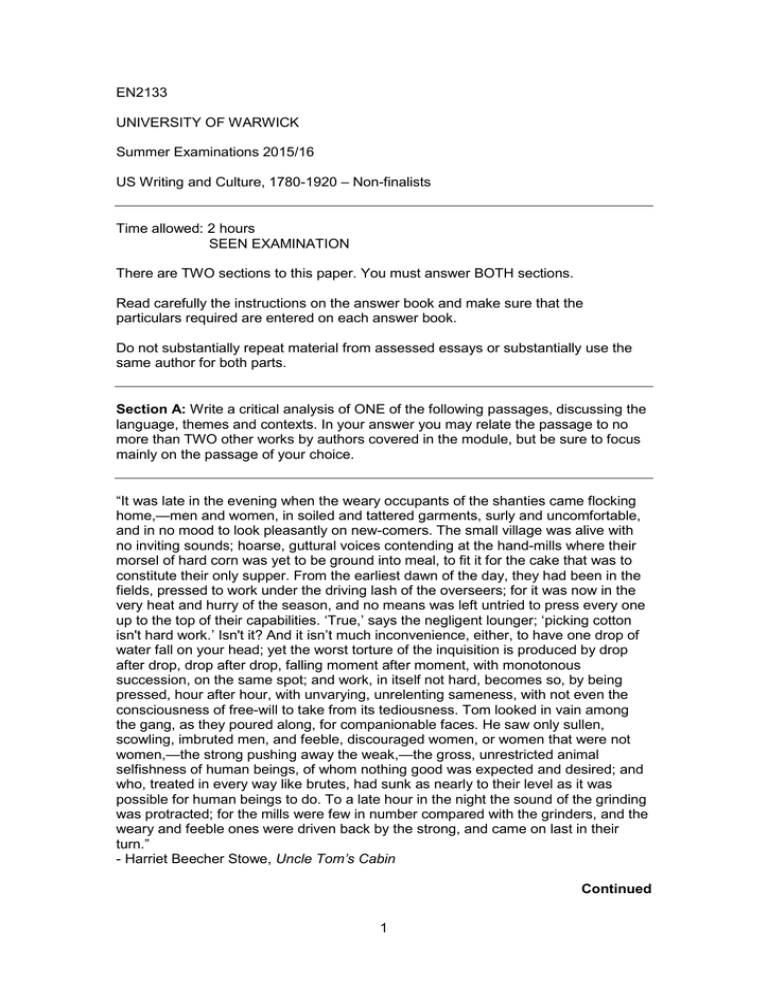

EN2133 UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK Summer Examinations 2015/16 US Writing and Culture, 1780-1920 – Non-finalists Time allowed: 2 hours SEEN EXAMINATION There are TWO sections to this paper. You must answer BOTH sections. Read carefully the instructions on the answer book and make sure that the particulars required are entered on each answer book. Do not substantially repeat material from assessed essays or substantially use the same author for both parts. Section A: Write a critical analysis of ONE of the following passages, discussing the language, themes and contexts. In your answer you may relate the passage to no more than TWO other works by authors covered in the module, but be sure to focus mainly on the passage of your choice. “It was late in the evening when the weary occupants of the shanties came flocking home,—men and women, in soiled and tattered garments, surly and uncomfortable, and in no mood to look pleasantly on new-comers. The small village was alive with no inviting sounds; hoarse, guttural voices contending at the hand-mills where their morsel of hard corn was yet to be ground into meal, to fit it for the cake that was to constitute their only supper. From the earliest dawn of the day, they had been in the fields, pressed to work under the driving lash of the overseers; for it was now in the very heat and hurry of the season, and no means was left untried to press every one up to the top of their capabilities. ‘True,’ says the negligent lounger; ‘picking cotton isn't hard work.’ Isn't it? And it isn’t much inconvenience, either, to have one drop of water fall on your head; yet the worst torture of the inquisition is produced by drop after drop, drop after drop, falling moment after moment, with monotonous succession, on the same spot; and work, in itself not hard, becomes so, by being pressed, hour after hour, with unvarying, unrelenting sameness, with not even the consciousness of free-will to take from its tediousness. Tom looked in vain among the gang, as they poured along, for companionable faces. He saw only sullen, scowling, imbruted men, and feeble, discouraged women, or women that were not women,—the strong pushing away the weak,—the gross, unrestricted animal selfishness of human beings, of whom nothing good was expected and desired; and who, treated in every way like brutes, had sunk as nearly to their level as it was possible for human beings to do. To a late hour in the night the sound of the grinding was protracted; for the mills were few in number compared with the grinders, and the weary and feeble ones were driven back by the strong, and came on last in their turn.” - Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin Continued 1 EN2133 “Pursuit of happiness, unalienable pursuit . . . right to life liberty and . . . A black moonless night; Jimmy Herf is walking alone up South Street. Behind the wharfhouses ships raise shadowy skeletons aloud. All these April nights combing the streets alone a skyscraper has obsessed him, a grooved building jutting up with uncountable bright windows falling onto him out of a scudding sky. Typewriters girls, glorified by Ziegfeld, smile and beckon to him from the windows. Ellie in a gold dress, Ellie made of thin gold oil absolutely lifelike beckoning from every window. And he walks round blocks and blocks looking for the door of the hummin tinselwindowed skyscraper, round blocks and blocks and still no door. Every time he closes his eyes the dream has hold of him, every time he stops arguing audibly with himself in pompous reasonable phrases the dream has hold of him. Young man to save your sanity you’ve got to do one of two things . . . Please mister where’s the door to this building? Round the block? Just round the block . . . one or two unalienable alternatives: go away in a dirty soft shirt or stay in a dean Arrow collar. But what’s the use of spending your whole life fleeing the City of Destruction? What about your unalienable right, Thirteen provinces? His mind unreeling phrases, he walks on doggedly. There’s nowhere in particular he wants to go. If only I still had faith in words.” -John Dos Passos Manhattan Transfer “A small shed had been added to my grandmother's house years ago. Some boards were laid across the joists at the top, and between these boards and the roof was a very small garret, never occupied by any thing but rats and mice. It was a pent roof, covered with nothing but shingles, according to the southern custom for such buildings. The garret was only nine feet long and seven wide. The highest part was three feet high, and sloped down abruptly to the loose board floor. There was no admission for either light or air. My uncle Phillip, who was a carpenter, had very skilfully made a concealed trap-door, which communicated with the storeroom. He had been doing this while I was waiting in the swamp. The storeroom opened upon a piazza. To this hole I was conveyed as soon as I entered the house. The air was stifling; the darkness total. A bed had been spread on the floor. I could sleep quite comfortably on one side; but the slope was so sudden that I could not turn on my other without hitting the roof. The rats and mice ran over my bed; but I was weary, and I slept such sleep as the wretched may, when a tempest has passed over them. Morning came. I knew it only by the noises I heard; for in my small den day and night were all the same. I suffered for air even more than for light. But I was not comfortless. I heard the voices of my children. There was joy and there was sadness in the sound. It made my tears flow. How I longed to speak to them! I was eager to look on their faces; but there was no hole, no crack, through which I could peep. This continued darkness was oppressive. It seemed horrible to sit or lie in a cramped position day after day, without one gleam of light. Yet I would have chosen this, rather than my lot as a slave, though white people considered it an easy one; and it was so compared with the fate of others. I was never cruelly overworked; I was never lacerated with the whip from head to foot; I was never so beaten and bruised that I could not turn from one side to the other; I never had my heel-strings cut to prevent my running away; I was never chained to a log and forced to drag it about, while I toiled in the fields from morning till night; I was never branded with hot iron, or torn by bloodhounds. On the contrary, I had always been kindly treated, and tenderly cared for, until I came into the hands of Dr. Flint. I had never wished for freedom till then. But though my life in slavery was comparatively devoid of hardships, God pity the woman who is compelled to lead such a life!” -Harriet Jacobs Incidents in the Life of a Salve Girl Continued 2 EN2133 “Mitchell started back, half-frightened, as, suddenly turning a corner, the white figure of a woman faced him in the darkness,—a woman, white, of giant proportions, crouching on the ground, her arms flung out in some wild gesture of warning. ‘Stop! Make that fire burn there!’ cried Kirby, stopping short. The flame burst out, flashing the gaunt figure into bold relief. Mitchell drew a long breath. ‘I thought it was alive,’ he said, going up curiously. The others followed. ‘Not marble, eh?’ asked Kirby, touching it. One of the lower overseers stopped. ‘Korl, Sir.’ ‘Who did it?’ ‘Can't say. Some of the hands; chipped it out in off-hours.’ ‘Chipped to some purpose, I should say. What a flesh-tint the stuff has! Do you see, Mitchell?’ ‘I see.’ He had stepped aside where the light fell boldest on the figure, looking at it in silence. There was not one line of beauty or grace in it: a nude woman's form, muscular, grown coarse with labor, the powerful limbs instinct with some one poignant longing. One idea: there it was in the tense, rigid muscles, the clutching hands, the wild, eager face, like that of a starving wolf’s. Kirby and Doctor May walked around it, critical, curious. Mitchell stood aloof, silent. The figure touched him strangely. ‘Not badly done,’ said Doctor May, ‘Where did the fellow learn that sweep of the muscles in the arm and hand? Look at them! They are groping, do you see?— clutching: the peculiar action of a man dying of thirst.’ ‘They have ample facilities for studying anatomy,’ sneered Kirby, glancing at the halfnaked figures. ‘Look,’ continued the Doctor, ‘at this bony wrist, and the strained sinews of the instep! A working-woman,—the very type of her class.’ ‘God forbid!’ muttered Mitchell. ‘Why?’ demanded May, ‘What does the fellow intend by the figure? I cannot catch the meaning.’ ‘Ask him,’ said the other, dryly, ‘There he stands,’—pointing to Wolfe, who stood with a group of men, leaning on his ash-rake. The Doctor beckoned him with the affable smile which kind-hearted men put on, when talking to these people. ‘Mr. Mitchell has picked you out as the man who did this,—I’m sure I don’t know why. But what did you mean by it?’ ‘She be hungry.’ -Rebecca Harding Davis Life in the Iron Mills Continued 3 EN2133 SECTION B: Answer ONE of the following questions. Your answer should be based on a discussion of TWO or THREE texts on the module. Do not attempt to cover more than THREE texts at length. 1. Analyze how the 19th- and early 20th-century novel depicts the potentials and pitfalls of solidarity between women of different racial or economic backgrounds. 2. What role does nature and natural spaces play in the larger social critiques of 19th- and early 20th-century literature? 3. How is sentimentalism either critiqued or deployed in the 19th- and early 20thcentury novel? 4. Consider the role that masculinity and femininity play in abolitionist literature – to what extent do these novels draw on and critique dominant ideas of masculinity of femininity? 5. “It is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.” Analyze 19th- and early 20th-century literature with regards to this observation by Henry Thoreau. End 4