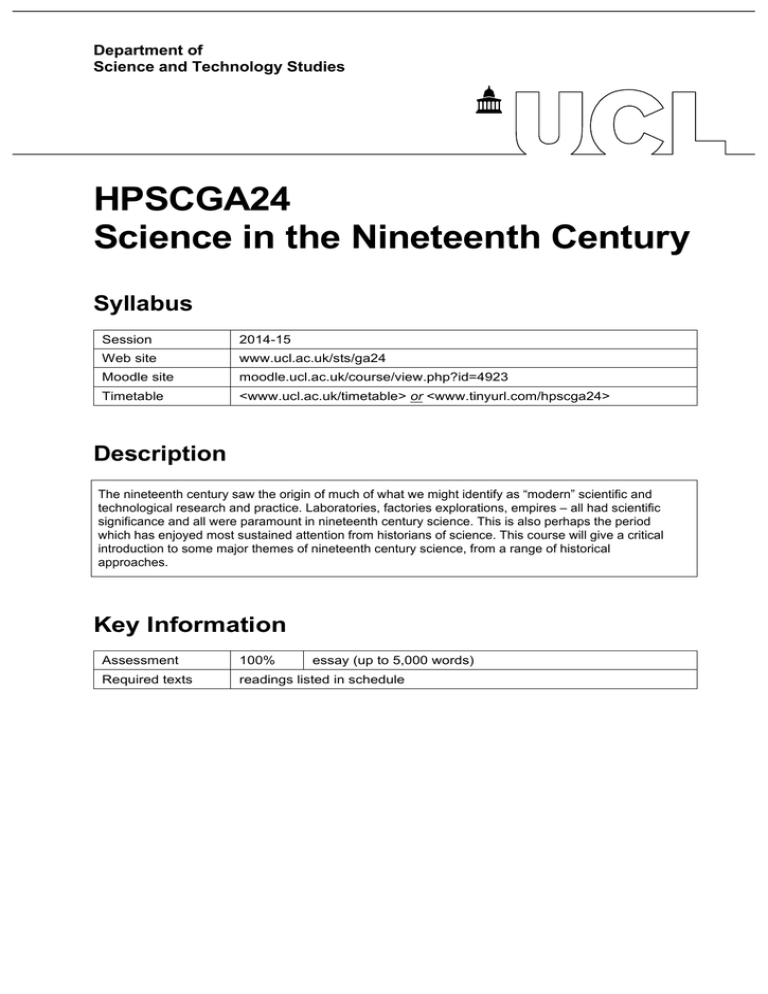

HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century Syllabus Department of

advertisement

Department of Science and Technology Studies HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century Syllabus Session 2014-15 Web site www.ucl.ac.uk/sts/ga24 Moodle site moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=4923 Timetable <www.ucl.ac.uk/timetable> or <www.tinyurl.com/hpscga24> Description The nineteenth century saw the origin of much of what we might identify as “modern” scientific and technological research and practice. Laboratories, factories explorations, empires – all had scientific significance and all were paramount in nineteenth century science. This is also perhaps the period which has enjoyed most sustained attention from historians of science. This course will give a critical introduction to some major themes of nineteenth century science, from a range of historical approaches. Key Information Assessment 100% essay (up to 5,000 words) Required texts readings listed in schedule HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus Module tutors Lead tutor Professor Joe Cain Contact J.Cain@ucl.ac.uk | t: 0207 679 3041 Office location 22 Gordon Square, Room 1.3 Office hours: Mondays and Thursdays 12:00-13:00 Tutor Dr Carole Reeves Contact C.Reeves@ucl.ac.uk | t: 0207 679 3223 Tutor Professor Frank James Contact Frank.James@ucl.ac.uk | t: 0207 679 7713 Aims and objectives aims This is a Masters-level module. HPSCGA24 pursues several kinds of goals. First, this is a module about the history of science and technology. This includes not only the substance of science, but also the people, places, contexts and consequences that surround and help to shape the course of events. Time is strictly limited in this module, so we’ve made some choices about how to focus the curriculum. Content aims are straightforward: • • • identify key themes in 19thC science, both regarding content and historiography study this period in an integrated way, combining written sources, material artifacts, physical geography, and cultural geography while the focus is primarily on the British diaspora, this module will integrate some limited material from other contexts and geographies The nineteenth century is a subject given considerable attention in English-speaking academic communities. The secondary literature is enormous. Another aim is to further develop the ability to assess interpretative work and relate evidence to interpretations. Primary sources will make up some of the essential readings. The aim is to promote a direct encounter with the activity in this period. Students are expected to further develop their skills working with original source materials: critical reading of testimony and evidence, plus critical reflection on their interpretation and extension. They also will be expected to develop further research skills to integrate archives, museum collections, and digital resources. objectives Knowledge By the end of this module students should be able to: • • • demonstrate key themes in 19thC science, both in content and historiography demonstrate an ability to research historical topics, including collecting and assessing primary sources, and relating primary sources to historiographical themes, demonstrate an ability to test historiographical arguments and develop relational points 2 HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus • demonstrate professional-level research skills that integrate archives, museum collections, and digital resources Transferrable and Key Skills By the end of this module students should be able to: • • • • • • demonstrate the ability to critically interpret both primary and secondary sources demonstrate skill in historical reasoning and comparative analysis demonstrate skill collecting primary materials relevant to the 19thC relate geographic and architectural knowledge to other types of historical artifacts approach new material in this course’s domain from a historical perspective and with a critical historian's eye demonstrate critical analysis of science communication and public engagement over a variety of venues Module plan Student responsibilities in this module will revolve around two components: seminars and a research project, culminating in a research essay. seminars A series of seminars is timetabled, with two contact hours per week. Seminars are related to specific required readings, and students should come to seminar having read the essential material. They should be prepared to actively discuss that material and engage with others. Additional readings and Web sites are suggested for continued investigation of module topics. I expect students to actively engage module themes. essay One 5,000-word essay is set for this module. Details are provided in this syllabus. To assist in a formative way, we ask students to prepare incrementally more involved tasks. Feedback will be provided with the aim of increased engagement with the historical research and the historiographical conversation. Schedule This schedule lists topics for class sessions. Most reading materials are available via Moodle, as are instructions for what we’d like you to prepare prior to the session. Unless otherwise noted, students are expected to have read the primary and secondary materials prior to class. Also on the schedule are due dates related to the assessment and dates for optional activities undertaken by the department. 3 HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus Schedule Wk Date Topic Activity 06 03/10 English Enlightenment primary: UoL (1826) secondary: Porter (1973) 07 10/10 Age of Industry primary: Roscoe (1839: i-47) secondary: Morrell (1972) and Reed (1992) 08 17/10 Imperial Science primary: Carey (1814) secondary: Drayton (2000: 50-128) and Headrick (1988: 3-17, 97-114) 09 24/10 Professionalization primary: Babbage (1830: iii-2) secondary: Morrell and Thackray (1981: 2-34) 26/10 Plan due submit via Moodle before 24:00 midnight 10 31/10 Rise of Hospitals and Biomedical Laboratories (Reeves) primary: Bernard (1865: 1-26) secondary: Jewson (2009) and Weiner (2003) 11 07/11 Reading Week no lectures 12/11 Prospectus due submit via Moodle before 24:00 midnight 14/11 Philosophical Geology and Deep time primary: Mantell (1851: 335-338) secondary: Rudwick (2000) and Secord (2004) 15/11 Optional event Visit to Maritime Greenwich Thames River cruise Queen’s House National Maritime Museum Royal Observatory, Greenwich 13 21/11 Industrialization and Mining (James) primary: TBC secondary: Hunt (1991) and James and Ray (1999) 14 28/11 Darwin and Darwinism primary: Darwin (1839: 453-478) secondary: Moore (1982) and Bowler (1988: 1-19) 15 05/12 Science and Religion (James) primary: Tyndall (1874) secondary: James (2005) and Fyfe (1997) 06/12 Optional Field Trip: Oxford Oxford Museum of Natural History Museum for the History of Science optional primary: Acland (1859) 12/12 Galton and Material Culture Venue: South Wing, room 23 primary: Galton (1872), Galton (1906) skim: Galton (1892) or Galton (1863) secondary: Waller (2001) and Van Wyhe (2004) 15/12 Draft due submit via Moodle before 24:00 midnight Winter closure 23/12 through 05/01 plan accordingly Final submission submit via Moodle before 24:00 midnight 12 16 06/01 4 HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus Assessment summary Assessment consists of one research project culminating in an 5000-word essay. To assist with project development and time management, this projects includes submission of a plan and a prospectus, which contribute to the final mark. Submission of a draft is expected, too, which is not assessed but which will receive formative feedback. coursework For the coursework, you have several options. Select one. Essays must be submitted via Moodle. Option 1: personalities Biography is a major avenue for professional discourse and for public support for history of science. These options use biography as a jumping point for integrating primary and historiographical research. 1. Florence Nightingale’s reputation and achievements have been subject to wide-ranging historiographical interpretation in the century since her death. Critically assess her ideas and achievement within the context of nineteenth century institutional or social reform. Advice: Lynn McDonald, ‘Florence Nightingale a hundred years on: who she was and what she was not,’ Women’s History Review 2010; 19(5): 721-40. A key primary source will be the collected works of Florence Nightingale (http://www.uoguelph.ca/~cwfn/), also in The Wellcome Library. The Florence Nightingale Museum is in Lambeth Palace Road, London SE1 (http://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk). Reeves is the lead on this question. 2. Charles Darwin was a sophisticated social agent. First, he was skilled at cultivating collaborators and informants. Second, he encouraged others to undertake work he found difficult or awkward. Third, he was no recluse, but he actively projected this image to increase his own control over events. Advice: The secondary literature on Darwin is substantial. Some of the best focusing on Darwin as a social agent has been written by Janet Browne, James Moore, and Jim Secord. The key primary sources will be the Darwin Correspondence Project and the Complete Work of Charles Darwin, both are online. Also useful might be materials from family members, close associates, and domestic staff. Darwin’s public profile can be followed in newspapers of the day. Cain is the lead on this question. 3. Michael Faraday combined disciplinary, civic, and commercial activities into an integrated vision of science distinct from the natural philosophy of the preceding generation. Advice: The secondary literature on Faraday is substantial, also. Some of the best comprehensive work has been written by Frank James and Geoffrey Cantor. The key primary sources will be the Correspondence of Michael Faraday. The Royal Institution has extensive materials about Faraday’s life and work. Faraday also is widely noted in newspapers and periodicals of the day. James is the lead on this question. Option 2: content questions These topics focus attention on research grounded in primary source materials. • • • • Scientists were engaged on all sides of the slavery question during the nineteenth century. Mary Anning didn’t simply find fossils, she developed expertise and actively commercialized the resources she acquired. University College Hospital presents a clear parallel for the rise of hospitals and scientific medicine, as in Paris. Technology redefined doctor-nurse-patient relationships during the nineteen century. 5 HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus • • • • • Science was one way military officers became gentlemen in the nineteenth century. Science was good for business. Use one of these cases: brewing, communication, fashion, travel. Natural history became industrialized in the nineteenth century. Compare the reception of Darwin’s (1859) Origin of Species in technical and public spheres in the first decade. Science became part of London's tourist landscape in the 19thC. Select a decade and investigate the advice and opportunities tourists had for visiting or engaging science while in the metropolis. Option 3: historiography These questions focus attention on research grounded in historiographical conversations. • • • • • • How do historians understand the relationship between professionals and amateurs in nineteenth century science? Research into late 19thC interactions between science and religion are focusing on the rise of “scientific naturalism”. Investigate this research direction and consider how it clarifies and obscures. The literature is growing rapidly about science in parlours, for children, in literature, and in entertainment in the nineteenth century. What does this add to historiography of science beyond making the point that science is present in these settings? Investigate how the evolving historiography of empire leads to redefinitions of the role of an institution such as Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Did science really play a major role in the development of railroads, shipping, communications, or sanitation? Choose one. What did it matter if evolution was a “radical” and “sensational” idea in the nineteenth century? plan for assessment A paper carrying this weight cannot be produced at the last minute. This module follows a plan for the tutor to assist with the research, thinking, and time management. The plan builds-in formative assessment and relatively light benchmarks to check progress. The writing plan follows a developmental sequence: • • • plan – (10%) A plan should identify the research question and present a preliminary inventory of resources to be used. A plan looks to the future and is speculative in nature. It should demonstrate effort towards dissecting the research problem, identifying elements that seem straightforward versus those that may require extra effort. It’s fine to identify elements where advice will be needed, too. My expectations for a plan are in the range of 750 words in outline form, plus an annotated bibliography listing primary sources and essential secondary sources, with annotations to identify why they might be useful. I would expect the sources to be filtered at this point, but I would not expect they’d be closely read. Your goal should be to show you have a focus and a starting point. You can expect formative assessment that points you to resources and relevant secondary material. prospectus – (10%) A prospectus should demonstrate your research is gaining specificity and clarity: what are you going to argue, what’s your plan for working through the task. The project will be a long way from completion, but you should demonstrate you’ve done sufficient work at this point to show a direction of travel. Some elements will be more-or-less done except for the writing up, but some elements will still be speculative. You should show you’re gaining a grasp of the primary material, and you should show you’re in conversation with secondary material more than simply extracting information. You can expect formative assessment that helps you focus and points you to highly relevant additional material. draft – (0%) – A draft is not marked, but it should be worth reading. I’m expecting solid writing something in the range of 50-70% percent at length, incomplete, sketchy in places, with notes on where I can be most helpful. For those drafts I receive on time, I will turn around comments within a few days. The most substantial the draft, the more useful my comments will be. No extensions for this deadline. 6 HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus • final submission – (80%) This will be the complete, polished research paper. Criteria for assessment will be provided. Normally, discrete marks only will be awarded for the plan and prospectus are: solid pass (receiving a mark of 80), basic pass (60), and bare pass (40), condonable fail (20) or uncondonable fail (0). Exceptions will be explained as they arise. supporting information I encourage you to discuss your essay with me well in advance of the due date. Best to e-mail to make an appointment. The criteria for assessment will be available via the Moodle site. Marks generally follow the departmental criteria for assessment. In sum, essays will be assessed on the following terms: • • • • • the depth of scholarship and use of resources beyond those in lecture and required reading the ability to identify both major and subtle points of the subject the extent of your critical assessment the evidence you provide for having reflected on and extended module content and themes the general scholarly presentation of the work performed My most common criticisms on student essays relate to: • • • • too much description/summary of readings and not enough analysis not developing your own argument no evidence of independent research terrible organisation and poor referencing techniques 7 HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus Reading list This is a complete list of essential readings, those used in seminars to explore essential themes of the module. Acland, Henry W., and John Ruskin. 1859. The Oxford Museum. London: Euston Grove Press. Babbage, Charles. 1830. Reflections on the Decline of Science in England, and on Some of its Causes. London: Fellowes. Bernard, Claude. 1865. An introduction to the study of experimental medicine. London: Macmillan. Bowler, Peter J. 1988. Non-Darwinian revolution: reinterpreting a historical myth. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. Carey, William. 1814. "Introduction." In Hortus Bengalensis, or a catalogue of the plants growing in the honourable East India Company’s botanic garden at Calcutta, edited by William Roxburgh, i-xii. Calcutta: Mission Press. Darwin, Charles Robert. 1839. Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle, Between 1826 and 1836, Describing the Examination of the Southern Shores of South America, and the Beagle's Circumnavigation of the Globe, in three volumes. Volume III. London: Henry Colburn. Drayton, Richard. 2000. Nature’s Government: Science, Imperial Britain, and the “Improvement” of the World. New Haven: Yale University Press. Fyfe, Aileen. 1997. "The reception of William Paley’s Natural Theology in the University of Cambridge." British Journal of the History of Science 30:321-335. Galton, Francis. 1863. Meteorographica, or Methods of Mapping the Weather. London: Macmillan and Co. Galton, Francis. 1872. "Statistical Enquiries into the Efficacy of Prayer." Fortnightly Review 68:125135. Galton, Francis. 1892. Fingerprints. London: Macmillan and Company. Galton, Francis. 1906. "Cutting a round cake on scientific principles." Nature 75:173. Headrick, Daniel 1988. The Tentacles of Progress : Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism, 1850-1940: Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism, 1850-1940. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hunt, Bruce. 1991. "Michael Faraday, cable telegraphy and the rise of field theory." History of Technology 13:1-19. James, Frank A. J. L. 2005. "An ‘open clash between Science and the Church’?: Wilberforce, Huxley and Hooker on Darwin at the British Association, Oxford, 1860." In Science and Beliefs: From Natural Philosophy to Natural Science, 1700-1900, edited by David Knight and Matthew Eddy, 171-193. Aldershot: Ashgate. James, Frank A. J. L., and M. Ray. 1999. "Science in the Pits: Michael Faraday, Charles Lyell and the Home Office Enquiry into the Explosion at Haswell Colliery, County Durham, in 1844." History and Technology 15:213-231. Jewson, Nick. 2009. "The Disappearance of the Sick-Man From Medical Cosmology, 1770-1870 [first published 1976]." International Journal of Epidemiology 38:622-633. Mantell, Gideon. 1851. Petrifactions and Their Teachings, or A Hand-Book to the Gallery of Organic Remains. London: Henry G. Bohn. 8 HPSCGA24 Science in the Nineteenth Century 2014-15 syllabus Moore, James. 1982. "Charles Darwin Lies in Westminster Abbey." Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 17 (1):97-113. Morrell, Jack. 1972. "The Chemist Breeders: The Research Schools of Liebig and Thomas Thomson." Ambix 19:1-46. Morrell, Jack , and Arnold Thackray. 1981. Gentlemen of Science: Early Years of the British Association for the Advancement of Science Oxford: Clarendon Press Porter, Roy. 1973. "The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of the Science of Geology." In Changing Perspectives in the History of Science, edited by Mikulas Teich and Robert Young, 320-343. London: Heinemann. Reed, P. 1992. "The British Chemical Industry and the Indigo Trade." British Journal for the History of Science 25 (84):113-125. Roscoe, Thomas. 1839. The London and Birmingham Railway; with the Home and Country Scenes on Each Side of the Line. London: Charles Tilt. Rudwick, Martin. 2000. "Georges Cuvier's paper museum of fossil bones." Archives of Natural History 27 (1):51-68. Secord, James A. 2004. "Knowledge in Transit." Isis 95 (4):654-672. Tyndall, John. 1874. Address Delivered Before the British Association Assembled at Belfast, With Additions. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. UoL. 1826. "University of London Prospectus [1826], with medical classes [1828]." In The Wrold of UCL 1828-1990, edited by Negley Harte and John North, 17-19, 32. London: University College London. Van Wyhe, John. 2004. Phrenology and the Origins of Victorian Scientific Naturalism. Vol. London: Ashgate. Waller, John. 2001. "Gentlemanly Men of Science: Sir Francis Galton and the Professionalization of the British Life-Sciences." Journal of the History of Biology 34 (1):83-114. Weiner, Dora B., and Michael J. Sauter. 2003. "The City of Paris and the Rise of Clinical Medicine." Osiris, 2nd Series 18:23-42. 9