Document 12680717

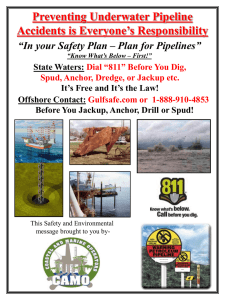

advertisement