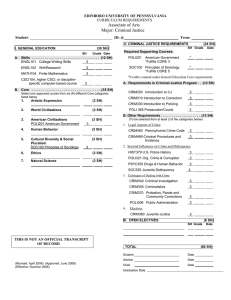

The Fear Factor Stephen Harper’s “Tough on Crime” Agenda Paula Mallea >

advertisement