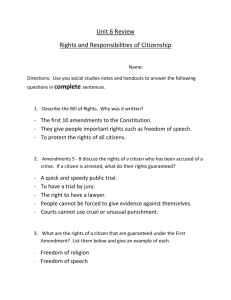

[The Impact of Civic Education on Schools, Students and Communities]

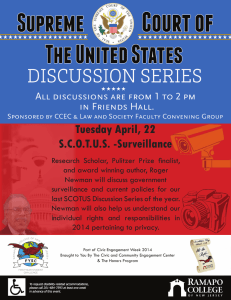

advertisement

![[The Impact of Civic Education on Schools, Students and Communities]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/012649506_1-23f99269800518b31b340bdb73afe882-768x994.png)