Between accountability, efficiency and structural constraints: Advocacy in EU cultural policy Centre

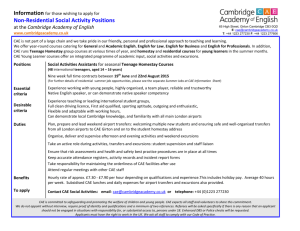

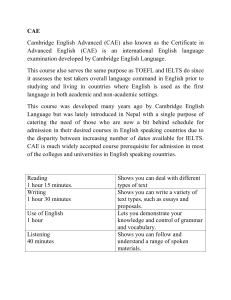

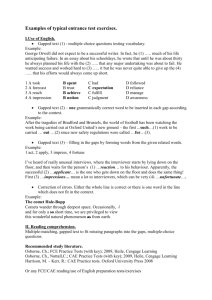

advertisement