Document 12639105

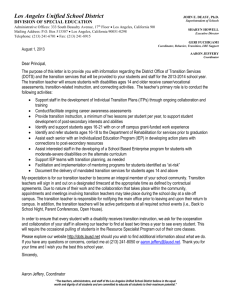

advertisement