QUEEN SQUARE ALUMNUS ASSOCIATION Issue 4 December 2012

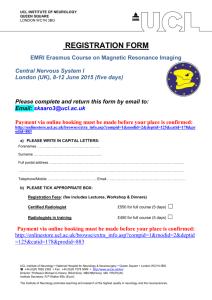

advertisement