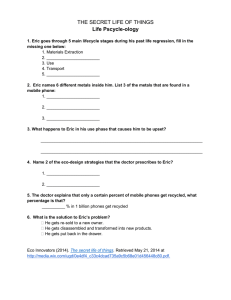

THE SEMANTICS OF PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVITY Lisa Bylinina Yasutada Sudo

advertisement

THE SEMANTICS OF PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVITY Lisa Bylinina Meertens Insitutuut • bylinina@gmail.com ! Yasutada Sudo U C L • y.sudo@ucl.ac.uk A D V A N C E D LO L I C O U R S E • E S S L L I 2 0 1 5 @ U N I V E R S I TAT PA M P E U FA B R A , B A R C E LO N A 10—14 August, 2015 PRACTICAL MATTERS Lecturers > Lisa Bylinina (Meertens Instituut) > Yasutada Sudo (UCL) > Guest lecturer: Eric McCready (Aoyama Gakuin University) Slides: bylinina.com/#essli; www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucjtudo/ The plan > Lecture 1 (Lisa): Introduction to perspective-sensitivity > Lecture 2 (Yasu): Shifting in attitude contexts and elsewhere > Lecture 3 (Yasu): Come and go > Lecture 4 (Eric): Epistemic modality and evidentials > Lecture 5 (Lisa): Subjectivity and perspective T H E C O U R S E I S B A S E D O N O U R ( B Y L I N I N A , M C C R E A DY, SUDO) ONGOING WORK ON PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVITY PLAN FOR TODAY > The phenomenon of perspective-sensitivity > Identifying perspective-sensitive items > Contexts of perspective-shifting > Perspective-sensitive items vs. indexicals > Perspective-sensitive items vs. pronominal anaphora > Towards a theory of perspective-sensitivity THIS LECTURE WILL BE MORE EMPIRICAL THAN THEORETICAL IT WILL SET THE PRELIMINARY EMPIRICAL GROUND FOR T H E T H E O R E T I C A L PA R T THE PHENOMENON Eric Lisa Tree Yasu (1) Eric is standing to the left of the tree Paraphrase: Eric is standing to the left of the tree looking from the perspective centre’s location > TRUE from Lisa’s point of view > FALSE from Yasu’s point of view ( 1 ) I S O N LY T R U E O R FA L S E W I T H R E S P E C T TO T H E LO C AT I O N OF THE PERSPECTIVE CENTRE (PC) THE PHENOMENON > Perspective-Sensitivity is a type of context-sensitivity: > Who counts as a PC is largely determined by the context ! > Perspective-sensitivity is triggered by certain lexical items such as left — Perspective Sensitive Items (PSIs) > Compare (1) and (2): Eric Lisa Tree Yasu (2) Eric is standing to the north of the tree IDENTIFYING PSIS Two (closely related) criteria: > Default speaker-orientation > Caveat 1: For some PSIs — e.g. predicates of personal taste — the default PC has a generic flavour (Moltmann 2010, Pearson 2013) > Caveat 2: In some contexts — e.g. narration — the default perspective is not the speaker’s > Caveat 3: Anaphors > ‘Shiftability’ > Shifting patterns set PSIs apart from other context-sensitive expressions SPEAKER-ORIENTATION Eric Lisa Tree Yasu (1) Eric is standing to the left of the tree. > Lisa utters (1) talking to her daughter Vera over the phone > You, as an observer, would say that what Lisa said was true > This is because by default the PC is taken to be the speaker > It would be strange to take Yasu’s perspective in this case SPEAKER-ORIENTATION? Eric Lisa Tree Yasu (3) Yasu, look! Eric is standing to the right of the tree. > Say, Lisa utters (3). Still, right can be interpreted under Yasu’s perspective. > In a narrative context, the PC can be the protagonist rather than the narrator: (4) [Yasu was walking in the wood for two hour when he saw something strange:] Eric was standing to the right of the tree! SPEAKER-ORIENTATION? > In a narrative context, the PC can be the protagonist rather than the narrator: (5) [Yasu was walking in the wood for two hour when he saw something strange:] Eric was standing to the right of the tree! > There seems to be some variation within the class of PSIs in how strong the speaker-orientation is: (6) [Looking at the cat finishing its food:] (Stephenson 2007) # Look! This cat food is tasty! > (6) has an inference that the speaker has actually tried the cat food, which means tasty is evaluated from the speaker’s perspective. PERSPECTIVE SHIFTING Eric Lisa Tree Yasu (7) Yasu thinks Eric is standing to the left of the tree. > It is possible, if not required, to take Yasu’s perspective in understanding left in (7). > If Lisa utters (7), she is reporting Yasu’s false belief (Eric is standing to the right of the tree from Yasu’s perspective) > This difference between (1) and (7) is one of the core facts we want a theory of perspective-sensitivity to account for. PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVE ITEMS • Relative locative expressions > e.g. to the left means ‘to the left looking from PC’s location’ (Mitchell 1986; Partee 1989; Oshima 2006) to/on the left, to/on the right, leftward, rightward, forward, backward, in front, in back, behind, across, nearby, close by, distant, remote, local, regional, clockwise, up, down, upstream, downstream, uphill, downhill, upwind, downwind, around the corner, within reach, outbound, inbound, come, go, approach PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVE ITEMS • Relative socio-cultural expressions > e.g. foreigner is ‘somebody from a different country from the PC’ (Mitchell 1986; Partee 1989; Oshima 2006) foreigner, foreign, at home, visiting (scholar), out of town, immigrant, alien, fellow citizen/student/passenger, compatriot, home ground, away/road game, home game, heathen (8) Yasu is a foreigner. > TRUE from Lisa’s perspective > FALSE from Wataru’s perspective PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVE ITEMS • Perspective-sensitive anaphora > anaphors refer to the PC • Japanese zibun (Abe 1997; Kuno 1972, 1973, 1987; Kuno & Kaburaki 1977; Nishigauchi 2014; Sells 1987) • Icelandic sig (Thrainsson 1976; Sigurðsson 1990; Reuland 2006; Hicks, 2009) • (9) Tamil ta(a)n (Sundaresan 2012) zibun-wa ZIBUN-TOP hoorensoo-ga kirai desu. SPINACH-NOM ‘I don’t like spinach’ HATE (JAPANESE) COP.FORMAL PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVE ITEMS Subjective predicates • i) Predicates of personal taste (PPTs) ! ! > e.g. interesting means ‘interesting to the PC’ (Lasersohn 2005; Stephenson 2007; Anand 2009; Pearson 2013) fun, boring, tedious, interesting, tasty, disgusting, pretty ! ii) Vague predicates > e.g. expensive means ‘expensive according to PC’s judgments’ (Kennedy 2013; Fleisher 2013; Bylinina to appear) wide, tall, expensive, heavy PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVE ITEMS • Epistemic modals > e.g. might means ‘it’s compatible with what PC knows that p’ might, may, possibly, likely • Evidentials > e.g. HEARSAY-EVID means ‘the PC has second-hand evidence that p’. Japanese evidentials: • • • • rashii (inferential) soo-da (hearsay) mitai-da (inferential) yoo-da (inferential) • • STEM-soo-da (inference based on direct perception) ppoi (inference based on direct perception) PERSPECTIVE-SENSITIVE ITEMS > Relative locative expressions > Relative socio-cultural expressions > Perspective-sensitive anaphora > Subjective predicates > Epistemic modals > Evidentials C O N T E X T- S E N S I T I V I T Y O F T H E S E I T E M S I S A C K N O W L E D G E D I N T H E L I T E R AT U R E , B U T T H E P O I N T I S R A R E LY ( I F AT A L L ) M A D E T H AT I T I S O F T H E S A M E K I N D, I . E . P E R S P E C T I V E - S E N S I T I V I T Y I N O U R S E N S E The plan: > Uniformity of this class (+ some differences) > Distinguishing PSIs ! from other kinds of context-sensitivity: • Indexicals; • Pronominal anaphora SHIFTING IN ATTITUDES > PC = subject of the attitude verb ( = obligatorily) (10) Yasu thinks Eric is standing to the left of the tree. (11) Vera thinks that Lisa is a foreigner. (12) Mary-wa John-ga MARY-TOP JOHN-NOM ZIBUN-ACC (to the left of the tree looking from Yasu’s / my point of view) (≈ Vera thinks that Lisa is from a different country than Vera / me) zibun-o aisiteiru to omotteimasu. LOVE C THINK.POLITE ‘Mary thinks that John loves her/me.’ (13) (14) Vera thinks that orxata is tasty. (tasty to Vera) Lisa thinks that this dress is expensive. (according to Lisa’s standards) (15) Yasu thinks that it might be raining. (it is compatible with what Yasu knows) (16) Sam-wa SAM-TOP ame-ga RAIN-NOM fut-tei-soo-da FAL-PROG-EVID-COP to itta. C SAID ‘Sam said it was likely to be raining.’ (Sam finds it likely) SHIFTING IN QUESTIONS > PC = hearer ( (17) = obligatorily) Was Eric standing to the left of the tree? (≈ Was John standing on the left from your / my point of view?) (18) Is Eric a foreigner? (≈ Is Eric from a different country than you / me?) (19) zibun-ga yaru no? (20) ZIBUN-NOM DO Q ‘Are you going to do it?’ zibun-ga yarimasu ZIBUN-NOM DO.FORMAL ‘Should I do it?’ (21) Is the movie interesting? (≈ Is the movie interesting to you?) (22) (23) Is John tall? (≈ In your judgment, does John count as a tall person?) Might John have left? (Is it compatible with what you know?) (24) ?Taro-wa Tokyoo-ni kaetta soo-na no? TARO-TOP TOKYO-TO WENT.BACK HEARSAY.EVID Q ‘Do you have hearsay evidence that Taro went back to Tokyo?’ ka? Q SHIFTING IN CONDITIONALS > PC = subject of the consequent (optionally) (25) (26) If a man on the left of the tree moves, Yasu will be startled. If a foreigner comes in, Yasu will be startled. (27) zibun-no hahaoya-ga ZIBUN-GEN MOTHER-NOM kuru nara, COME IF John-wa JOHN-TOP kimasen. COME.NEG.POLITE ‘If his / my mother comes, John will not come.’ (28) (29) If a handsome man comes in, Lisa will be startled. If Lisa buys an expensive backpack, Yasu will be startled. (30) If it might rain, Vera will take an umbrella. (31) ame-ga furu ppoi RAIN-NOM FALL EVID.DIR.INF IF nara, John-wa kasa-o motteiku. JOHN-TOP UMBRELLA-ACC TAKE ‘If it looks (to John / me) like it will rain, John will take an umbrella.’ > The same observed with other adjuncts (temporal clauses) VP-INTERNAL POSITIONS > PC = subject of the clause (optionally) (32) Yasu introduced a man on the left of the tree to Vera. (33) Yasu introduced a foreigner to Vera. (34) John-wa JOHN-TOP [zibun-o ZIBUN-ACC shitteiru] otoko-o KNOW MAN-ACC shootaishimashita. INVITED.POLITE ‘John invited a man who knew him / me.’ (35) Yasu was reading an interesting book. (36) Vera talked to a man who might be her mother's old friend. (37) Lisa bought an expensive backpack. (38) John-wa JOHN-TOP [roshiago-o RUSSIAN-ACC hanashi-soo-na] otoko-o SPEAK.EVID.INF-COP MAN-ACC shootaishita. INVITED ‘John invited a man who he / I though might speak Russian.’ VP-INTERNAL POSITIONS > PC = linearly preceding internal argument (optionally) (38) (39) Yasu introduced Lisa to the man on the left. Yasu introduced Lisa to a foreigner. (40) John-wa JOHN-TOP Mary-ni MARY-TO zibun-no hon-o ZIBUN-GEN BOOK-ACC agemashita. GAVE.POLITE ‘John gave Mary John’s / Mary’s / my book.’ (41) Eric introduced Yasu to an attractive linguist. (42) Yasu gave Vera an expensive book. (43) Yasu introduced Eric to someone who might be a murderer. (44) John-wa Mary-ni roshiago-o JOHN-TOP MARY-TO otoko-o shookaishita. MAN-ACC RUSSIAN-ACC hanas-e-soo-na SPEAK-CAN-EVID.DIR.INF-COP INTRODUCED ‘John introduced to Mary a man who looked (to me / John / Mary) like a Russian speaker.’ NO SHIFTING IN SUBJECT > PSIs in subject-internal positions can not take the object as a PC: (45) [A man on the left of the tree] introduced Yasu to my friend. (≠ On the left of the tree from Yasu’s point of view) (46) A foreigner introduced Eric to my friend. (≠ A person from a different country than Eric) (47) [zibun-o ZIBUN-ACC shitteiru] otoko-ga John-o shootaishita. KNOW INVITED MAN-NOM JOHN-ACC ‘A man who knew *John / me invited John.’ (48) [A handsome man] introduced Yasu to my friend. (≠ A man who Yasu finds handsome introduced Yasu to my friend) (49) [A man who might be a murderer] introduced Yasu to my friend. (≠ A man who Yasu thought could be a murderer introduced Yasu to my friend) (50) [roshiago-o ZIBUN-ACC hanashi-soo-na] otoko-ga John-o SPEAK-EVID.INF-COP MAN-NOM JOHN-ACC shootaishita. INVITED ‘A man who *John / I thought might speak Russian invited John.’ NO SHIFTING IN SUBJECT? > Potential counterexample (Phillipe Schlenker, p.c.): (51) Foreigners hate British government. > We think this shifting possibility has to do with the genericity of the sentence > Compare an episodic statement: (52) A foreigner called his British friend. > The shifted interpretation is harder to get in (53). > Shifted interpretations of all classes of PSIs are available in generic contexts GENERIC CONTEXTS > Generics in the broad sense — deontics, always (53) Local bars are the best. (54) Bad books don’t sell well. (55) zibun-no ie-ga ZIBUN-GEN HOUSE-NOM ichiban-da. BEST-COP ‘One’s own house is the best.’ (56) People who might have contracted an infection abroad are subject to quarantine. (57) kaigai-de kansensyoo-ni ABROAD-LOC INFECTION-DAT kakatta CONTRACTED rasii EVID hito-wa minna PERSON-TOP ALL kakuris-are-ru. QUARANTINE-PASS-PRES ‘People who have reasons to believe that they might have contracted an infection abroad are subject to quarantine.’ SUMMING UP SO FAR > PSIs shift (at least) in the following contexts: > Under attitude verbs > In conditionals > In questions > VP-internally > In generic contexts > The shift is sometimes optional, sometimes obligatory > Always optional (class 1): spatial, socio-cultural, anaphora > Sometimes obligatory (class 2): subjective, modals, evidentials Attitude contexts Class 1 Class 2 ◇ ◻ Conditiona Questions VP-internal ls ◇ ◻ ◇ ◇ ◇ ◇ (◇=shift possible; Generic ◇ ◇ =shift obligatory) WHAT SHOULD WE DO? > We said that perspective-sensitivity is a kind of contextsensitivity and then looked at the shifting profile of PSIs > There are other items that are context-sensitive: > Indexicals (for example, I) > Pronominal anaphora (for example, he) > Should we reduce perspective-sensitivity to one of these phenomena? > Depends on how similar to PSIs they are The plan: > Compare PSIs and indexicals > Compare PSIs and pronominal anaphora > Preview of the analysis of perspective-sensitivity > (We will leave the account for class 1 vs. class 2 distinction for L5) PSIS VS. INDEXICALS > Indexicals — in particular, 1P pronouns (I) — show speakerorientation, quite like PSIs. > However, they do so in a much more rigid way than PSIs: > With a sufficient prior context the default PC can be somebody other than the speaker. > For instance, in a narrative context, it is natural to take the PC to be the main protagonist, rather than the narrator. > This is virtually impossible with 1P pronouns, no matter how rich the context is. > In matrix contexts, the denotations of indexicals are fixed by the current context of utterance. PSIS VS. INDEXICALS > There are language where indexicals shift (‘indexical shifting’) (Kaplan 1977; Schlenker 1999, 2003; Anand 2006; Sudo 2012) ! (58) ! (Amharic) ! ! > They only shift in a subset of attitude contexts in a subset of languages. > They do not shift in questions. > They do not shift in non-attitude modal contexts. INDEXICAL-SHIFTING CONTEXTS (SUNDARESAN 2012) PSIS VS. INDEXICALS Indexicals PSIs Attitude contexts Questions ✓/* ✓ * ✓ Conditiona VP-internal ls * ✓ * ✓ Generic * ✓ > Perspective shifting is much more pervasive and is observed in languages and constructions where indexicals do not shift. > We conclude perspective shifting can not be reduced to indexical shifting. PSIS AND PRONOUNS > Partee (1989) identifies three classes of uses that 3P pronouns and PSIs share: > Deictic uses > Discourse-anaphoric uses > Bound-variable uses PRONOUNS (59) (60) (61) D E I C T I C O R D E M O N S T R AT I V E Who’s he? DISCOURSE-ANAPHORIC A woman walked in. She sat down. B O U N D VA R I A B L E Every man believed he was right. PSIS (62) (63) Eric visited a local bar. D E I C T I C O R D E M O N S T R AT I V E (i) Utterance location DISCOURSE-ANAPHORIC (ii) Wherever Eric was at the relevant time Every sports fan in the country was at a local bar watching the playoffs. ( M I T C H E L L 1 9 8 6 ; PA R T E E 1 9 8 9 ) B O U N D VA R I A B L E PSIS AND PRONOUNS > Bound-variable uses are available for all PSIs: (64) Nobody introduced a man on the left to my friend. (≈ Nobody introduced a man on the left from their / my perspective to my friend) (65) Nobody introduced a foreigner to my friend. (≈ Nobody introduced someone from a different country than them / me) (66) daremo ANYBODY [zibun-o ZIBUN-ACC shitteiru] otoko-o KNOW MAN-ACC shootaishimasendeshita. INVITED.POLITE.NEG ‘Nobody invited a man who knew them / me.’ (67) Nobody read an interesting book. (≈ Nobody read a book that’s interesting for them / me.) (68) Nobody talked to a man who might be his mother’s old friend. (≈ Nobody talked to a man they / I thought could be his mother’s old friend.) (69) daremo [roshiago-o ANYBODY RUSSIAN-ACC hanashi-soo-na] otoko-o SPEAK-EVID.INF-COP MAN-ACC shootaishinakatta. INVITED.NEG ‘Nobody invited a man who they / I thought might speak Russian.’ PSIS AND PRONOUNS > Partee (1989) identifies more similarities between perspective and pronominal anaphora: > Weak-Crossover effects: PRONOUNS (70) Only hisi top aide got a good picture of Reagani (71) #?Only hisi top aide got a good picture of every senatori (72) Every senatori directed a smile at hisi top aide PSIS (73) Only the nearesti photographer got a good picture of Reagani (74) #?Only the nearesti photographer got a good picture of every senatori (75) Every senatori directed a smile at the nearesti photographer PSIS AND PRONOUNS > Partee (1989) identifies more similarities between perspective and pronominal anaphora: > ‘Donkey anaphora’ PRONOUNS (77) (78) (79) Every man who owns a donkey bits it PSIS Every man who stole a car abandoned it 2 hours later. Every man who stole a car abandoned it within 20 miles. > PC component of PSIs can co-vary with time/location of event in the relative clause of the subject > This is analogous with the interpretation of it in (64), where it co-varies with the donkey in the subject rel.cl. PSIS AND PRONOUNS Summing up so far: > Partee (1989) identifies similarities between perspective and pronominal anaphora: > Deictic or demonstrative uses > Discourse-anaphoric uses > Bound-variable uses > Weak-crossover effects > ‘Donkey anaphora’ Consequences: > These observations naturally follow if PSIs come with a silent anaphoric pronoun (syntactically or semantically) > This ‘pronominal approach’ to PSIs would analyse, say, local as differing minimally from local to him / her > However, there are reasons for scepticism PSIS VS. PRONOUNS > Partee’s (1989) observations that cast doubt on this approach: > It’s not always possible to overtly express the alleged pronominal argument of PSIs. In some cases, where it is expressed overtly, it looks like an adjunct rather than an argument: ! (80) ! ! ! ! ! ! (81) (82) Eric had a black spot on the middle of his forehead. To the left of it (from Eric’s point of view / from an observer’s point of view) was a green ‘A.’ ...*? to the left of it from / for him [foreign to them/that country], [a stranger to them/that country], *[a foreigner to them/that country] > Overall, there seems to be no uniform manner in which PSIs express the hidden pronominal argument PSIS VS. PRONOUNS > Partee’s (1989) observations that cast doubt on this approach: > Even for PSIs that can take an overt argument, there are configurations where its overt realisation is forbidden: (83) (84) In all my travels, whenever I have called for a doctor, one has arrived (*there) within an hour. In all my travels, whenever I have called for a doctor from any place, one has arrived there within an hour. > The PSI in (83) can not combine with an explicit pronominal argument, unless an overt antecedent for this pronoun is added T H E S E C O N S I D E R AT I O N S A R E S U G G E S T I V E , B U T N O T CONCLUSIVE. W E A D D M O R E E M P I R I C A L A R G U M E N T S F O R PA R T E E ’ S H U N C H PSIS VS. PRONOUNS New arguments against the pronominal analysis ! ! ! IN THEIR ANAPHORIC USES, 3P PRONOUNS IN P R I N C I P L E C A N R E F E R B A C K TO A N Y I N D I V I D U A L S T H AT H A V E B E E N M E N T I O N E D I N T H E D I S C O U R S E ( A S FA R A S T H E Φ - F E AT U R E S M ATC H ) , W H I L E P S I S A R E M U C H L E S S FLEXIBLE IN THIS REGARD ! > There are thematic restrictions on DPs that PSIs can anchor to; > PSIs obey ‘shift-together locally’ (two PSIs occurring in the same ‘domain’ must refer to the same PC) (cf. Anand & Nevins 2004, Shklovsky & Sudo 2014 — ‘shifttogether’ for indexicals) THEMATIC RESTRICTIONS > For instance, 3P pronouns can refer back to the comitative phrase, while PSIs cannot: (85) I went to a restaurant with Yasu yesterday. He was a little tired. (86) I went to a restaurant with Yasu yesterday. a. The man sitting on the left was eating natto. (on the left from my / *Yasu’s perspective) b. The waiter was a foreigner. (from a different country from me / *Yasu) c. The duck was delicious. (tasted good to me / *Yasu) d. It must have been around 9 pm. ( It is compatible with what I know / *Yasu knows) THEMATIC RESTRICTIONS > For instance, 3P pronouns can refer back to the comitative phrase, while PSIs cannot: (87) [I went to a restaurant with Yasu yesterday.] sono THIS mise-wa ima RESTAURANT-TOP NOW totemo ninki VERY POPULAR rashii EVID.HEARSAY ‘This restaurant is very popular now, I hear / *Yasu hears.’ (88) Stas-ga STAS-NOM tegami-ga LETTER-NOM Vera-to VERA-WITH dekake GO.OUT yootoshiteita-ra, zibun-ate-no WAS.ABOUT.TO-WHEN, ZIBUN-ADDRESSED-GEN maikondekita ARRIVED.UNEXPECTEDLY ‘As Stas was leaving home with Vera, a letter addressed to him / *her came in.’ > Unlike zibun, the regular 3P pronoun kare can refer to the comitative phrase in a sentence like (74). THEMATIC RESTRICTIONS > The restriction is not specific about comitative phrases. Consider conjoined subjects: (89) [Vera is Russian, Eric is American] Vera and Eric met a foreigner. > (75) can’t describe a situation where they met an American > In contrast, 3P pronouns can refer to one of the conjuncts: (90) Vera and Eric met her violin teacher. (91) Vera-to VERA-AND Eric-wa ERIC-TOP zibun-no sensei-ni ZIBUN-GEN TEACHER-DAT atta MET ‘Vera and Eric met their teacher’ / *’Vera and Eric met her teacher’ (92) Vera-to VERA-AND Eric-wa ERIC-TOP kanojo-no SHE-GEN sensei-ni TEACHER-DAT atta MET ’Vera and Eric met her teacher’ + more restrictions we don’t know about yet SHIFT-TOGETHER LOCALLY > Two 3P pronouns (in some local domain) can generally have different referents: (93) Erice said that Yasuw broke hise,w computer in hise,w office. > Two PSIs in the same ‘domain’ must refer to the same PC: (94) [Wei is from China but not the speaker. Assume also that the speaker and Wei are facing each other] Wei talked to a foreigner on the left. Speaker Wei Speaker Wei ✓ * * ✓ SHIFT-TOGETHER LOCALLY > To establish that shift-together holds for PSIs as a group, we need to check all possible combinations of PSIs of different classes. > For example, here’s a PPT and a socio-cultural PSI: (95) Eric read a book written by a talented foreigner. Speaker Eric Speaker Eric ✓ * * ✓ > We won’t do it here, but see (Bylinina, McCready & Sudo 2015a-c) for more data SHIFT-TOGETHER LOCALLY > Shift-together seems to hold for zibun: (96) John-wa JOHN-TOP Bill-ni [zibun-no hon-to BILL-TO ZIBUN-GEN zibun-no CD]-o miseta BOOK-AND ZIBUN-GEN CD-ACC SHOWED ‘John showed Bill self’s book and self’s CD’ John Bill John Bill ✓ * * ✓ > But, in fact, mixed interpretations are pretty bad with kare too: (97) John-wa JOHN-TOP Bill-ni [kare-no BILL-TO HIS hon-to BOOK-AND kare-no HIS ‘John showed Bill his book and his CD.’ John Bill John Bill ✓ ?? ?? ✓ CD]-o miseta CD-ACC SHOWED SHIFT-TOGETHER LOCALLY > Moreover, if there are two different PSIs in positions similar to those in (99), mixed interpretations seem to become possible: (99) John-wa JOHN-TOP miseta SHOWED Bill-ni [gakukokugo-no BILL-TO FOREIGN.LANGUAGE-GEN hon-to BOOK-AND zibun-no CD]-o ZIBUN-GEN CD-ACC ‘John showed Bill a foreign book and self’s CD.’ John Bill John Bill ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ > Why is it the case that sometimes shift-together seems to be observed, while in other cases it, apparently, isn’t? > To figure this out, we need a better understanding of the domains of perspective-shifting SHIFTING DOMAINS > Shift-together allows us to discern domains of shifting > The direct object and the indirect object constitute different domains, because shift-together is not observed: (100) Eric introduced [DO a foreigner] [IO to a talented linguist]. (101) John-wa zibun-no musume-ni JOHN-TOP ZIBUN-GEN shookaishimashita. DAUGHTER-TO zibun-no musuko-o ZIBUN-GEN SON-ACC INTRODUCED ‘John introduced self's daughter to self's son.’ > In particular, VP as a whole is not a shifting domain (pace Sundaresan 2012), given that the PC for a PSI used as a main predicate does not shift to the subject. SUMMING UP > PSIs are different from indexicals: Attitude Conditio VPQuestions contexts nals internal Indexicals PSIs ✓/* ✓ * ✓ * ✓ * ✓ Generic Tense * ✓ * ✓/* > Perspective is different from pronominal anaphora: > Perspective-shifting is more restricted > There seems to be a hierarchy of some sort: ! Indexicals > Perspective > Pronominal anaphora THEORETICAL PROSPECTS The intuition > Not reducing perspective-sensitivity to indexicality or pronominal anaphora > Instead, we want to treat these different kinds of items as special cases of more general contextdependency > Indexicals, third person pronouns and PSIs — and context dependent items more generally — refer to ‘contexts’, although they refer to different aspects of contexts IMMEDIATE COMPLICATIONS > We could just add a PC parameter to the interpretation function, but: Eric Lisa Tree Yasu > Orientation: Is Eris standing to the left of the tree from Lisa’s perspective? > Time: (102) Every man who stole a car abandoned it 2 hours later. (103) When Eric turned around, he saw a chair to the left of the table. > World? Addressee? > This will be discussed in Lecture 2. OUTLOOK > Today we had a lot of data > We tried to empirically delineate the phenomenon and characterise the class of PSIs > We contrasted PSIs with indexicals and with pronominal anaphora > This means we cannot straightforwardly adopt existing analyses of these other phenomena to PSIs > Some work needs to be done to build the analysis of perspective > Moreover, PSIs do not form a totally homogeneous class > We’ll look at shifting in more detail and formulate an analysis > We’ll look at different individual cases of PSIs to understand the variation within the class of PSIs REFERENCES Abe, Jun. (1997) The locality of zibun and logophoricity. Technical report 08CE1001, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan. Anand, Pranav. (2006) De De Se. Ph.D. Thesis, MIT. Anand, Pranav. (2009) Kinds of taste. Ms. Anand, Pranav and Valentine Hacquard. (2013) Epistemics and attitudes. Semantics and Pragmatics 6(8): 1–59. Anand, Pranav and Andrew Nevins. (2004) Shifty Indexicals in Changing Contexts. Proceedings of SALT 14, CLC Publication: 20–37. Bylinina, Lisa (to appear) Judge-dependence in degree constructions. Accepted for publication in Journal of Semantics. Fleisher, Nicholas (2013). The dynamics of subjectivity. In Proceedings of SALT 23, 276–294. Hicks, Glyn. 2009. The derivation of anaphoric relations. Linguistik Aktuell. John Benjamins. Kaplan, David. (1977) Demonstratives: An essay on the semantics, logic, metaphysics, and epistemology ofdemonstratives and other indexicals. Ms. [Published in Joseph Almog, John Perry, and Howard Wettstein (eds.). (1989) Themes from Kaplan. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 481–563.] Kennedy, C. (2013). Two sources of subjectivity: Qualitative assessment and dimensional uncertainty. Inquiry, 56(2-3), 258-277. Kuno, Susumu. (1972) Pronominalization, Reflexivization, and Direct Discourse. Linguistic Inquiry, 3: 161–195. Kuno, Susumu. (1973) The Structure of the Japanese Language. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Kuno, Susumu. (1987) Functional Syntax: Anaphora, Discourse and Empathy. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Kuno, Susumu & Etsuko Kaburaki. (1977) Empathy and Syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 8: 627–672. Lasersohn, Peter. (2005) Context dependence, disagreement, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy 28: 643–686. REFERENCES Mitchell, Jonathan. (1986) The Formal Semantics of Point of View. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Moltmann, Friederike. (2010) Relative truth and the first person. Philosophical Studies 150: 187–220. Nishigauchi, Taisuke. (2014) Reflexive binding: awareness and empathy from a syntactic point of view. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 23(2): 157–206. Oshima, David Y. (2006) Perspectives in Reported Discourse. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University. Partee, Barbara. (1989) Binding Implicit Variables in Quantified Contexts. CLS 25: 342–365. Pearson, Hazel. (2013) The Sense of Self: Topics in the Semantics of De Se Expressions. Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University. Reuland, E. (2006) Icelandic Logophoric Anaphora, in The Blackwell Companion to Syntax (eds M. Everaert and H. van Riemsdijk), Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA, USA. Schlenker, Philippe. (1999) Propositional Attitudes and Indexicality. Ph.D. Thesis, MIT. Schlenker, Philippe. (2003) A plea for monsters. Linguistics and Philosophy, 26(1): 29–120. Sells, Peter. (1987) Aspects of logophoricity. Linguistic Inquiry, 18(3): 445–479. Shklovsky, Kirill & Yasutada Sudo. (2014) The syntax of monsters. Linguistic Inquiry, 45(3): 381–402. Sigurðsson, Halldór Ármann. 1990. Long distance reflexives and moods in Icelandic. In Modern Icelandic syntax, edited by Joan Maling and Annie Zaenen, pp. 309–346. Academic Press, New York. Stephenson, Tamina. (2007) Towards a Theory of Subjective Meaning. Ph.D. Thesis, MIT. Sudo, Yasutada. (2012) On the Semantics of Phi-Features on Pronouns. Ph.D. Thesis, MIT. Sundaresan, Sandhya. (2012) Context and Co(reference) in the syntax and its interfaces. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tromsø/Universität Stuttgart Thrainsson, H. (1976). Reflexives and subjunctives in Icelandic. In Sixth Annual Meeting of the North Eastern Linguistics Society.