On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese Hironobu Kasai

advertisement

Syntax 17:2, June 2014, 168–188

DOI: 10.1111/synt.12016

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements

in Japanese

Hironobu Kasai

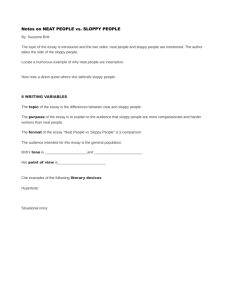

Abstract. This paper argues that the null clausal complement in Japanese is not derived via CP

ellipsis but is rather an instance of pro. The availability of sloppy interpretation in the

construction under investigation apparently argues that ellipsis is involved there, but it is

revealed under close scrutiny of the sloppy interpretation in question that the null clausal

complement behaves like deep anaphora, not like surface anaphora.

1. Introduction

One of the most characteristic properties of Japanese is that arguments are allowed to

be left unpronounced, as shown in (1), where the unpronounced argument is indicated

by e.

(1) John-ga [e Mary-o

nagutta to] itta.

John-NOM Mary-ACC hit

that said

‘John said that he hit Mary.’

There has been much discussion in the literature on the nature of null arguments in

Japanese (see Zushi 2003 and Takahashi 2008a for reviews). One prevalent view is

due to Kuroda (1965), who suggests that null arguments are analyzed as empty

pronouns (see Ohso 1976, Hoji 1985, and Saito 1985, among others). This view is

challenged by Hasegawa (1985), however. Extending Huang’s (1984) analysis to

Japanese null arguments, Hasegawa argues that some null arguments in Japanese are

variables bound by empty topic operators. Another interesting alternative is

investigated by Otani & Whitman (1991), whose analysis is originally due to

Huang’s (1988, 1991) analysis based on some instances of null objects in Chinese.

Under Otani & Whitman’s analysis, some of the null arguments are derived via VP

ellipsis preceded by V raising out of the ellipsis site. Thus, (2a) has the derivation

given in (2b).

(2) a. John-wa zibun-no tegami-o suteta.

Mary-mo e suteta.

John-TOP self-GEN letter-ACC discarded Mary-also discarded.

‘John threw out his letter. Mary did too.’ (Otani & Whitman 1991:346–347)

b. John-wa zibun-no tegami-o suteta. Mary-mo [VP zibun-no tegami-o t1]

suteta1.

Parts of this paper were presented at Hogeschool-Universiteit Brussels and Simon Fraser University. I

would like to thank the audiences for helpful questions and comments. I am also grateful to reviewers for

Syntax for valuable comments. Thanks also go to Duncan Wotley for suggesting stylistic improvements.

All remaining errors are my own.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 169

Otani & Whitman’s analysis easily accommodates the fact that the null argument

allows a sloppy reading as well as a strict reading. The second conjunct in (2a) has the

sloppy reading in which Mary also discarded her letter as well as the strict reading in

which Mary also discarded John’s letter. Example (2) patterns with VP ellipsis in (3),

which allows both a sloppy reading and a strict reading.

(3) Peter likes his picture, and Joan does too.

a. Peter likes his picture, and Joan likes Peter’s picture too.

b. Peter likes his picture, and Joan likes Joan’s picture too.

Strict

Sloppy

Otani & Whitman’s ellipsis approach is criticized by Hoji (1998), Kim (1999), and

Takahashi (2008a) but is elaborated by Oku (1998), among others. He argues that the

elided category in question is not VP but NP, under which (2a) is analyzed in the

following way:

(4) John-wa zibun-no tegami-o suteta. Mary-mo [NP zibun-no tegami-o] suteta.

Some researchers take the availability of the sloppy reading in (2a) as evidence for the

ellipsis approach (Oku 1998; Saito 2004, 2007; and Tanaka 2008, among many

others). Their argument against postulating an empty pronoun for the null argument

in (2a) is based on the absence of sloppy interpretation in the following example,

where the empty pronoun in (2a) is replaced with the overt pronoun sore ‘it’:

(5) John-wa zibun-no tegami-o suteta.

Mary-mo sore-o

John-TOP self-GEN letter-ACC discarded Mary-also it-ACC

suteta.

discarded

‘John threw out his letters. Mary also threw it out.’

Strict, *Sloppy

If the null argument in (2a) were an empty pronoun, the sloppy reading would be

unexpected, similarly to (5), which leads them to conclude that the sloppy reading in

(2a) should be derived without recourse to pro but through an alternative way.1 They

1

Their crucial assumption is that pronouns do not allow sloppy interpretation, whether they are overt or

covert. However, this assumption is not uncontroversial. There are cases where pronouns do allow sloppy

interpretation. Let us consider (ia), which is a typical example of the so-called paycheck pronoun. Example

(ia) is paraphrased as (ib); that is, it in (ia) refers to his2 paycheck.

(i) a. The man who1 gives his1 paycheck to his wife is wiser than the man who2 gives it to his

mistress.

(Karttunen 1969:114)

b. The man who1 gives his1 paycheck to his wife is wiser than the man who2 gives his2 paycheck

to his mistress.

I thank a reviewer for bringing my attention to paycheck pronouns under this context. A detailed discussion

of paycheck pronouns is beyond the scope of this paper, but see Karttunen 1969, Cooper 1979, Engdahl

1986, Jacobson 2000, and references therein for their analyses of paycheck pronouns.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

170 Hironobu Kasai

claim that the alternative strategy in question is argument ellipsis.2 Since Oku, several

researchers have presented further arguments for the NP-ellipsis approach and null

arguments have been one of the hotly debated topics of Japanese syntax (see Kim

1999; Saito 2004; and Takahashi 2006, 2008a, 2008b, among many others).

Compared with null nominal arguments in Japanese, null clausal complements in

Japanese have not received much attention in the literature. However, Shinohara

(2006), Saito (2007), and Tanaka (2008) put forward the hypothesis that clausal

complements can also undergo ellipsis like nominal arguments in Japanese, which is

referred to as the CP-ellipsis approach in this paper. Under the CP-ellipsis approach,

the complement of the matrix verb undergoes ellipsis, as shown in (6b).

(6) a. Hanako-wa [zibun-no teian-ga

saiyoosareru to] omotteiru ga,

Hanako-TOP self-GEN proposal-NOM accepted-be that think

though

Taroo-wa e omotteinai.

Taroo-TOP think-not

‘Hanako thinks that her proposal will be accepted, but Taroo does not think

that her/his proposal will be accepted.’

(Saito 2007:210)

b. Taroo-wa [zibun-no teian-ga saiyoosareru to] omotteinai.

Example (6a) has the interpretation where Taroo does not think that Hanako’s

proposal will be accepted. In addition to this strict reading, (6a) can be interpreted

sloppily; that is, (6a) also has the interpretation where Taroo does not think that his

own proposal will be accepted. This sloppy reading is readily expected if (6a) is

analyzed as (6b), where the clausal complement undergoes ellipsis. Contrary to the

CP-ellipsis approach, this paper argues that the apparent CP ellipsis is not derived

via ellipsis, but it is analyzed in terms of pro, which means that the categorial status

2

Saito (2004) makes a similar argument to show that the missing subject of the second conjunct in (i)

undergoes CP ellipsis, as shown in (ii).

(i) John-wa [zibun-ga naze sikarareta ka] wakatteinai ga,

Mary-wa [e naze da ka] wakatteiru.

John-TOP self-NOM why scolded-was Q know-not though Mary-TOP why is Q know

‘John doesn’t know why he was scolded, but Mary knows why.’

(Saito 2004:31)

no]]-ga

[naze da ka] wakatteiru.

(ii) Mary-wa [CP Op1 [TP zibun-ga t1 sikarareta

Mary-TOP

self-NOM

scolded-was that-NOM why is Q know

‘Mary knows why it is that she was scolded.’

The second conjunct of (i) involves a cleft construction in the embedded clause. Saito argues that the

presuppositional subject undergoes ellipsis. (Saito assumes that null operator movement is involved in

the cleft construction in Japanese.) As noted by Takahashi (1994:n. 3), (i) has a sloppy reading; that is,

the second conjunct of (i) can be interpreted as ‘Mary knows why she was scolded.’ In contrast, when the

pronoun sore appears as the subject of the embedded clause in place of the empty subject as given in (iii),

the relevant sloppy reading is not available.

(iii) Mary-wa [sore-ga naze da ka] wakatteiru.

Mary-TOP it-NOM why is Q know

‘Mary knows why.’

(Saito 2004:31)

On the assumption that pro also disallows sloppy interpretation like the overt pronoun sore, Saito argues

that the second conjunct of (i) should be derived via ellipsis. However, as argued in the next section, this

assumption should be reconsidered.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 171

of the missing material in (6) is not really CP but NP/DP under the proposed

analysis.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 shows that the sloppy interpretation

found in the null clausal complement in Japanese behaves like deep anaphora, not

like surface anaphora in the sense of Hankamer & Sag (1976). Section 3 presents two

more arguments against the CP-ellipsis approach based on the so-called mix reading

and the observation that nothing can move out of the null clausal complement.

Section 4 summarizes the paper.

2. A Close Look at the Sloppy Interpretation in the Null Clausal Complement

2.1 Sloppy Interpretation in Deep Anaphora

As reviewed in the previous section, the availability of sloppy interpretation has been

often taken as an argument for the argument ellipsis approach. However, the

correlation between the availability of sloppy interpretation and ellipsis is worth

reconsidering. As shown in (7), null objects in Japanese can be used without a

linguistic antecedent, which is generally taken as one of the properties of deep

anaphora.

(7) Bill-ga e tataita.

Bill-NOM hit

‘Bill hit e.’

In contrast to deep anaphora, surface anaphora (ellipsis) needs a linguistic antecedent,

as shown in (8).

(8) a. [Observing Hankamer attempting to stuff a 12” ball through a 6” hoop]

Sag: #I don’t see why you even try to e.

(Hankamer & Sag 1976:414)

b. [Hankamer produces a gun, points it offstage and fires, whereupon a scream

is heard.]

Sag: #Jesus, I wonder who e.

(Hankamer & Sag 1976:408)

Keeping this in mind, let us consider the following example:

(9) [Watching a boy hitting his arm]

Taroo: Hanako-mo e yoku tataiteru yo.

Hanako-also often hit

PARTICLE

‘Hanako also often hits e.’

The absence of a linguistic antecedent in (9) indicates that the null argument does not

involve ellipsis but rather is an empty pronoun. Under the assumption that pronouns

do not allow sloppy interpretation, it is expected that the null argument in Japanese

would not allow sloppy interpretation in (9). However, this expectation is not borne

out. In (9), Taroo’s utterance can mean that Hanako often also hits her arm. That is,

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

172 Hironobu Kasai

the null argument allows sloppy interpretation, despite the absence of a linguistic

antecedent.3 The interpretation in (9) suggests that sloppy interpretation is obtainable,

even when ellipsis is not involved.4

Dalrymple (1991) and Hoji (1998, 2003) also point out that deep anaphora can

provide sloppy interpretation. For example, as Hoji (2003) observes, do the same

thing, which behaves like deep anaphora in the sense that it can be used without a

linguistic antecedent in (10), allows a sloppy reading, as shown in (11). Example

(11B) can be interpreted as ‘Bill washed Bill’s car on that rainy day.’

(10) [Observing someone put soy sauce on a hamburger]

My brother does the same thing.

(11) A: John washed his car on that rainy day.

B: Bill did the same thing.

(Hoji 2003:176)

Strict, Sloppy (Hoji 2003:189)

To the extent that sloppy interpretation is available with deep anaphora as well, the

sloppy reading in (2a) is not a compelling piece of evidence for the argument ellipsis

approach anymore. The sloppy reading in (2a) is readily expected by pro, on a par

with (9).

Similarly, the sloppy reading in (6a) does not support the CP-ellipsis approach,

either. It is also captured under the hypothesis that the null clausal complement under

investigation is an instance of pro, which is the hypothesis put forward in this paper.

In fact, as shown in (12), an overt pronoun can yield sloppy interpretation, when it

appears as the complement of a propositional-attitude verb.

(12) Every foolish man believes that he will win the lottery; no wise man believes it.

(Jacobson 2000:135)

3

Contrary to the proposal in this paper, Takahashi (2008a) suggests that null arguments do not allow

sloppy interpretation, when they have no linguistic antecedent, based on (i).

(i) [Watching a boy hitting himself]

Taroo: Hanako-mo e tataku daroo.

Hanako-also hit

will

‘Hanako will hit e, too.’

(Takahashi 2008a:420)

According to Takahashi, Taroo’s utterance cannot mean that Hanako will hit herself, which indicates that

sloppy interpretation is unavailable. However, the absence of sloppy interpretation in (i) is independently

captured in terms of binding condition B. Note that (i) gives rise to a violation of condition B on the

assumption that the null argument in (i) is pro. If the relevant condition B violation is circumvented, the

sloppy interpretation becomes available, as shown in (9) in the text.

4

Some pronouns behave in a similar way. They also allow sloppy interpretation, even if they have no

linguistic antecedent. The relevant example is given below:

(i) [A new faculty member picks up her first paycheck from her mailbox. Waving it in the air, she

can say to a colleague:]

Do most faculty members deposit it in the Credit Union?

(Jacobson 2000:89)

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 173

As shown in (7), Japanese null arguments behave like deep anaphora in the sense that

it can be used without a linguistic antecedent. The null clausal complement behaves

in a similar way, as shown in (13).

(13) [John suspects that Mary, who is his girlfriend, flirts with

someone else. John and his friend happen to watch Mary’s

flirting with someone else.]

John: Zituwa pro mae-kara e omottetanda yonaa.

in-fact

before-from thought-be PARTICLE

‘In fact, I have long thought e.’

In (13), what John has thought can be interpreted as Mary’s flirting with someone

else. The absence of a linguistic antecedent in (13) confirms the claim that the null

clausal complement behaves like deep anaphora.

Under the general assumption that pro occupies the position which NPs do, one

might wonder whether pro is capable of occupying the position which CP

complements occupy. However, this apparent categorial mismatch does not occur

because the verbs participating in the null-clausal-complement construction can also

take nominal arguments. Let us take the verb omou ‘think’ as an example. It takes a

CP complement, which is headed by to ‘that’, but it can also take nominal arguments

headed by koto ‘fact’, as shown in (14a). Example (14b) confirms the same point with

the verb iu ‘say’.

(14) a. Taroo-wa iroirona-koto-o

omotta.

Taroo-TOP various-thing-ACC thought

‘Taro thought about various things.’

b. Taroo-wa Hanako-to

onazi-koto-o

itta.

Taroo-TOP Hanako-with same-thing-ACC said.

‘Taroo said the same thing as Hanako.’

The existence of the accusative case particles attached to the objects shows that the

objects are nominal. Verbs taking interrogative CP complements such as siritagatteiru ‘wonder’ and tazuneru ‘ask’ given in (15) can also take nominal

arguments.

(15) a. Taroo-ga Hanako-ga kuru kadooka siritagatteita/tazuneta.

Taroo-NOM Hanako-NOM come whether wondered/asked

‘Taroo wondered/asked whether Hanako would come.’

b. Taroo-ga Hanako-no-koto-o

siritagatteita/tazuneta.

Taroo-NOM Hanako-GEN-matter-ACC wondered/asked

‘Taroo wondered/asked about Hanako.’

Given the discussion so far, one might think that sloppy interpretation plays no role in

investigating the issue as to whether constructions which apparently involve ellipsis

are indeed derived via ellipsis or not, because both surface anaphora and deep

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

174 Hironobu Kasai

anaphora allow sloppy interpretation. However, it is not the case. As Hoji (1998,

2003) convincingly shows, the sloppy interpretation in surface anaphora behaves

differently from that in deep anaphora, which enables one to detect whether the

construction under investigation involves surface anaphora or deep anaphora. In the

rest of this section, I show that the null clausal complement behaves like deep

anaphora, by taking a closer look at the sloppy interpretation available in the null

clausal complement.

2.2 Sloppy Interpretation with a-Occurrences

Given that bound-variable anaphora is involved in sloppy readings in surface

anaphora (Sag 1976 and Williams 1977), it is reasonable to assume that the relevant

sloppy interpretation also obeys the constraints which bound-variable anaphora does

(see also Lasnik 1976, Reinhart 1983, and Hoji 2003). One of the constraints on

bound-variable anaphora is that names such as John fail to work as a bound variable.5

To put it in another way, bound variables should be b-occurrences, not a-occurrences

in the terms of Fiengo & May (1994). The value of the former depends on that of

another. In contrast, the value of the latter is independent. Thus, (16a) cannot have the

bound-variable interpretation given in (16b).

(16) a. Only John voted for John’s father.

b. ONLY x, x = John, x voted for x’s father.

This constraint is also observed in sloppy readings in surface anaphora. Let us

consider the following contrast:

(17) a. John1 will [VP vote for his1 father]; I want Bill to [VP e] too.

Strict, Sloppy

b. John1 will [VP vote for John’s1 father]; I want Bill to [VP e] too.

Strict, *Sloppy

(Hoji 2003:188–189)

5

Another constraint on bound-variable anaphora is the c-command requirement. However, as a reviewer

points out, it is controversial if sloppy readings in surface anaphora also obey this requirement. It has been

reported that some examples allow sloppy interpretation even when antecedents do not c-command their

bindees (see Wescoat 1989, Dalrymple, Shieber & Pereira 1991, and Fiengo & May 1994). Consider (i),

which is adapted from examples due to Wescoat 1989, cited in Dalrymple, Shieber & Pereira 1991.)

(i) The policeman who arrested John read him his rights, and the one who arrested Bill did e, too.

(Fiengo & May 1994:108)

John does not c-command him in the antecedent, but the sloppy interpretation in the ellipsis site is

available. It is beyond the scope of this paper to investigate how the sloppy interpretation is obtained given

in cases like (i). One of the solutions, provided by Tomioka (1999), is that the sloppy interpretation in

question is obtained by interpreting the pronoun in the ellipsis site as an E-type pronoun, which can be

anaphoric to its antecedent, even though there is no c-command relation between them. See also B€uring

2004 and Elbourne 2005 for relevant discussion.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 175

In (17a), the pronoun in the elided VP can be interpreted as either John or Bill. In

contrast, the relevant sloppy reading becomes unavailable in (17b), where the

pronoun in the antecedent of the ellipsis site is replaced with the name John. The

second sentence of (17b) cannot be interpreted as ‘I want Bill to vote for Bill’s

father.’ The unavailability of the relevant sloppy reading is explained because names

are not qualified as bound variables.

Interestingly, as Hoji (1998, 2003) observes, the sloppy reading in deep anaphora

behaves differently from that in surface anaphora with respect to this point. As given

in (17), to obtain a sloppy reading in surface anaphora, it is necessary to use a

b-occurrence as a bound variable. However, the sloppy interpretation which is

available in deep anaphora is free from such a requirement. Let us go back to (11).

Even if his in (11A) is replaced with John, the sloppy reading is still available, as

shown in (18). B’s utterance can be interpreted as ‘Bill washed Bill’s car on that rainy

day.’

(18) A: John washed John’s car on that rainy day.

B: Bill did the same thing.

Strict, Sloppy (Hoji 2003:189)

As shown in Hoji (1998), the same effect is observed in the null-object construction

in Japanese. The relevant example is given in (19), which also allows a sloppy

reading. The second example can be interpreted as ‘Bill also washed Bill’s car.’

Recall that, as shown in (7), null objects in Japanese can be used without a linguistic

antecedent, which is generally taken as one of the properties of deep anaphora.

(19) John-ga John-no kuruma-o aratta; Bill-mo e aratta.

John-NOM John-GEN car-ACC

washed Bill-also washed

‘John washed John’s car; Bill also washed e.’

(Hoji 1998:145)

Distinguishing the sloppy reading found in deep anaphora (which does not involve

bound-variable anaphora at LF) from the sloppy reading in surface anaphora, Hoji

(1998) refers to the former as the “sloppy-like” reading.

Bearing this in mind, let us turn to the null clausal complement. Under the

CP-ellipsis analysis, it is expected that when a name is used as a bindee in the same

way as (17b), sloppy interpretation should be unavailable. This expectation is not

borne out by (20), however.6

(20) a. Sensei-ga

Taroo-ni [Taroo-no hon-ga

nusumareta to] minna-no

teacher-NOM Taroo-DAT Taroo-GEN book-NOM stolen-was that all-GEN

mae-de iw-ase-ta.

front-at say-make-PAST

A reviewer and his or her informants find (20) quite marginal in the first place, let alone in the sloppy

reading in question. According to the reviewer, the marginality is due to the repetition of the names in the

example. This paper offers no explanation for the nature of the marginality felt by some speakers. Further

investigation is left for future research.

6

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

176 Hironobu Kasai

b. Sensei-wa Hanako-ni-mo e minna-no mae-de iw-ase-ta.

teacher-TOP Hanako-DAT-also all-GEN

front-at say-make-PAST

‘The teacher made Taroo say in front of everyone that Taroo’s book had

been stolen. The teacher also made Hanako say in front of everyone e.’

In contrast to (17b), (20b) can be interpreted as ‘the teacher made Hanako say in front

of everyone that her book had been stolen.’7 One might say that names in Japanese

are b-occurrences, not a-occurrences, which allows (20b) to have sloppy interpretation. However, it is not the case. As the following example shows, names in

Japanese cannot be used as bound variables, which suggests that they are not

b-occurrences:

(21) *[Toyota-sae]1-ga Toyota1-no sitauke-o

hihansi-(tara) . . .

Toyota-even-NOM Toyota-GEN subsidiary-ACC criticize-if

‘(if) [even Toyota]1 criticizes its1 subsidiaries, . . .’

(Hoji 2003:180)

Hoji (1991, 1995) also points out that the NP with the demonstrative a ‘that’ is not a

b-occurrence. As shown in (22), it cannot be used as a bound variable.

(22) *[Toyota-sae]1-ga a-soko1-no

sitauke-o

hihansi-(tara) . . .

Toyota-even-NOM that-place-GEN subsidiary-ACC criticize-if

‘(if) [even Toyota]1 criticizes its1 subsidiaries, . . .’

(Hoji 2003:180)

It is expected that sloppy interpretation would be available if the NP with the relevant

demonstrative is used as a bindee. The expectation is borne out by the following

example:

(23) a. Sensei-ga

a-no-gakusei-ni1

[a-itu-no1

hon-ga

teacher-NOM that-GEN-student-DAT that-guy-GEN book-NOM

nusumareta to] minna-no mae-de iw-ase-ta.

stolen-was that all-GEN

front-at say-make-PAST

7

Under Saito’s (2004) analysis, the missing subject in (ia), which allows sloppy interpretation, is derived

via the ellipsis of the presuppositional CP subject, as shown in (ib). See also footnote 1.

(i) a. John-wa [zibun-ga naze sikarareta ka] yoku wakatteiru ga,

Mary-wa [e naze da ka]

though Mary-TOP why is Q

John-TOP self-NOM why scolded Q much know

mattaku wakattei-nai.

at-all

know-not

‘John knows much about why he was scolded, but Mary never knows why.’

b. Mary-wa [CP Op1 [TP zibun-ga t1 sikarareta

no]]-ga [naze da ka] wakattei-nai.

Mary-TOP

self-NOM scolded-was that-NOM why is Q know-not

‘Mary never knows why it is that she was scolded.’

When zibun-ga ‘self-NOM’ in (ia) is replaced with John-ga ‘John-NOM’, which is an a-occurrence, similarly

to (20), the sloppy reading is still available, which suggests that the null subject in (i) is not derived via

ellipsis, contrary to Saito (2004).

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 177

b. Sensei-wa kono-gakusei-ni-mo e minna-no mae-de iw-ase-ta.

teacher-TOP this-student-DAT-also all-GEN

front-at say-make-PAST

‘The teacher made that student say in front of everyone that that guy’s

book had been stolen. The teacher also made this student say in front of

everyone e.’

The example allows the sloppy reading where the teacher also made this student say

in front of everyone that this guy’s book had been stolen.

The upshot of the discussion so far is that the availability of sloppy interpretation

by itself does not offer any compelling piece of evidence for the CP-ellipsis approach,

because deep anaphora also allows sloppy interpretation. By closely examining the

behavior of the sloppy interpretation in the null clausal complement, it has been

argued that the construction under investigation behaves like deep anaphora, not like

surface anaphora. The next section offers two more pieces of evidence against the

CP-ellipsis approach.8

3. Two More Arguments against the CP-Ellipsis Approach

3.1 The Absence of the So-Called Mix Reading

This section presents two more arguments against the CP-ellipsis approach. One is

concerned with the (un)availability of the so-called mix reading, discussed by Dahl

(1974) and Fiengo & May (1994). Dahl observes that (24a) allows the three readings

in (25a–c) but does not allow (25d).

(24) a. Max said he saw his mother; Oscar did too.

b. Max said his mother saw him; Oscar did too.

8

One might wonder whether (ia), where the CP complement of the verb in the comparative clause is

missing, is derived from (ib) via CP ellipsis.

(i) a. John-wa Mary-ga omotteita yori takusan hon-o

katta.

John-TOP Mary-NOM believed than many book-ACC bought

‘John bought more books than Mary believed.’

(Ishii 1991:164)

b. John-wa Mary-ga [John-ga e kau to] omotteita yori takusan hon-o

katta.

John-TOP Mary-NOM John-NOM buy that believed than many book-ACC bought

It is speculated at this point that (ia) will receive a similar analysis to the following English example, which

is analogous to (ia):

(ii) Jones published more papers than Smith thought e.

(Kennedy & Merchant 2000:(1))

Kennedy & Merchant argue that the gap in (ii) is a trace of a phonologically null nominal operator, which is

a variant of the overt operators in (iii) (see Kennedy & Merchant 2000 for their arguments).

(iii) a. What was {necessary/expected/predicted/reported}?

b. The committee took much longer to decide than what was expected.

(Kennedy & Merchant 2000:(22)–(23))

If the null nominal operator in question is available in Japanese as well, (ia) will be derived without recourse

to CP ellipsis. A detailed investigation of the construction in (ia) is left for future research.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

178 Hironobu Kasai

(25) a. Max1

b. Max1

c. Max1

d. *Max1

said

said

said

said

he1

he1

he1

he1

saw

saw

saw

saw

his1

his1

his1

his1

mother;

mother;

mother;

mother;

Oscar2

Oscar2

Oscar2

Oscar2

said

said

said

said

he1

he2

he2

he1

saw

saw

saw

saw

his1

his2

his1

his2

mother.

mother.

mother.

mother.

On the other hand, (24b) is four-ways ambiguous, given in (26).

(26) a.

b.

c.

d.

Max1

Max1

Max1

Max1

said

said

said

said

his1

his1

his1

his1

mother

mother

mother

mother

saw

saw

saw

saw

him1;

him1;

him1;

him1;

Oscar2

Oscar2

Oscar2

Oscar2

said

said

said

said

his1

his2

his2

his1

mother

mother

mother

mother

saw

saw

saw

saw

him1.

him2.

him1.

him2.

The readings given in (25c,d) and (26c,d) are referred to as “mix readings.” Hoji

(2003) claims that the mix readings can be explained on the assumption that surface

anaphora such as VP ellipsis involves a full-fledged structure that undergoes ellipsis.9

9

Hoji (2003) proposes that the establishment of an asymmetrical relation of dependency at syntax, which

he calls “Formal Dependency” (FD), is a necessary condition on the availability of mix readings. He

independently proposes the following three necessary conditions for FD:

(i) The three necessary conditions for FD (A, B), where A and B are in argument positions:

a. B is [+b].

b. A c-commands B.

c. A is not in the local domain of B.

(Hoji 2003:179)

Given (ia), B is required to be a b-occurrence in the sense of Fiengo & May (1994). The local domain in

(ic) is what is postulated for binding condition B. Under his analysis, the mix readings in (25c), (26c), and

(26d) are captured through the following LF representations, respectively:

(ii) a. Maxa1 [VP said heb saw hisa1 mother]; Oscara2 [VP said heb saw hisa1 mother].

b. Maxa1 [VP said hisb mother saw hima1]; Oscara2 [VP said hisb mother saw hima1].

c. Maxa1 [VP said hisa1 mother saw himb]; Oscara2 [VP said hisa1 mother saw himb].

(Hoji 2003:210)

In (iia), FD (Max1, he) and FD (Oscar1, he) are established because the three conditions in (i) are satisfied.

Examples (iib) and (iic) receive a similar explanation. Furthermore, Hoji postulates an additional constraint

on FD to capture the unavailability of the mix reading in (25d) (for details, see Hoji 2003:sect. 5).

Hoji’s analysis expects that the failure of the establishment of FD would lead to the unavailability of mix

readings. This expectation is borne out with the b-occurrence requirement on FD in (ia). Fukaya & Hoji

(1999) point out that when the pronouns in (24) are replaced with Max or Max’s, the mix readings become

unavailable. This is because Max is not a b-occurrence, but an a-occurrence. Let us also consider the

following examples:

(iii) a. The policeman who arrested John1 said that he1 had hit his1 roommate, and the one who

arrested Bill did, too.

b. The policeman who arrested John1 said that his1 roommate had hit him1, and the one who

arrested Bill did, too.

(Hoji 2003:227)

In (iiia) and (iiib), John fails to c-command the pronouns, which prevents John from establishing a formal

dependency with any pronoun. It is expected that neither (iiia) nor (iiib) would allow mix interpretation.

According to him, this expectation is also borne out. Hoji also shows that the failure of the establishment

of FD due to the violation of (ic) makes mix interpretation unavailable, based on the Case-marked

comparative construction in Japanese (for details, see Hoji 2003:sect. 6).

This paper will not discuss the issue concerning how to derive mix readings. However, I use the (un)

availability of mix readings as a diagnostic for investigating the nature of the null clausal complement in

Japanese.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 179

He argues that if deep anaphora were represented fully at LF in the same way as

surface anaphora, deep anaphora should behave like surface anaphora with respect to

the (un)availability of mix interpretation. However, as Hoji (2003) points out, in

contrast to VP ellipsis, deep anaphora do the same thing does not allow any mix

reading. The second conjunct of (27a) can be interpreted neither as (28a) nor as (28b).

Similarly, the second conjunct of (27b) does not have the mix readings given in (28c)

and (28d). The unavailability of mix interpretation with deep anaphora indicates that

deep anaphora cannot be represented in the same way as surface anaphora.

(27) a. John said/declared (before the class) that his roommate had hit him, and

Bill did the same thing.

b. John said/declared (before the class) that he had hit his roommate, and

Bill did the same thing.

(Hoji 2003:218)

(28) a.

b.

c.

d.

Bill

Bill

Bill

Bill

said/declared

said/declared

said/declared

said/declared

(before

(before

(before

(before

the

the

the

the

class)

class)

class)

class)

that

that

that

that

Bill’s roommate had hit John.

John’s roommate had hit Bill.

Bill had hit John’s roommate.

John had hit Bill’s roommate.

Hoji (2003) observes that soo suru ‘do so’ in Japanese, which is an instance of deep

anaphora, also disallows any mix reading. The relevant example is given in (29).

Example (29b) can be interpreted neither as (30a) nor as (30b).

(29) a. Sensei-ga

Bill-ni [kare-no

teacher-NOM Bill-DAT he-GEN

iw-ase-ta.

say-make-PAST

b. Sensei-wa John-ni-mo

soo

teacher-TOP John-DAT-also so

‘The teacher made Bill say that

John do so.’

ruumumeito-ga kare-o nagutta to]

roommate-NOM he-ACC hit

that

s-ase-ta.

do-make-PAST

his roommate hit him. The teacher made

(Hoji 2003:219)

(30) a. The teacher made John1 say that his1 roommate hit Bill.

b. The teacher made John1 say that Bill’s roommate hit him1.

The following example also patterns with (29) in the sense that the mix readings

given in (32) are not available:

(31) a. Sensei-ga

Bill-ni [kare-ga kare-no ruumumeito-o nagutta to]

teacher-NOM Bill-DAT he-NOM he-GEN roommate-ACC hit

that

iw-ase-ta.

say-make-PAST

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

180 Hironobu Kasai

b. Sensei-wa John-ni-mo

soo s-ase-ta.

teacher-TOP John-DAT-also so do-make-PAST

‘The teacher made Bill say that he hit his roommate. The teacher made

John do so.’

(32) a. The teacher made John1 say that he1 hit Bill’s roommate.

b. The teacher made John1 say that Bill hit his1 roommate.

Keeping this in mind, let us consider (33). If the null clausal complement in (33b)

were an instance of surface anaphora such as VP ellipsis, (34c), which is one of the

mix readings, would be allowed. However, this expectation is not borne out. No mix

reading is available for (33b).

(33) a. Sensei-ga Bill-ni [kare-ga kare-no ruumumeito-o nagutta to]

teacher-NOM Bill-DAT he-NOM he-GEN roommate-ACC hit

that

iw-ase-ta.

say-make-PAST

b. Sensei-wa John-ni-mo e iw-ase-ta.

teacher-TOP John-DAT-also say-make-PAST

‘The teacher made Bill say that he hit his roommate. The teacher made John

say e.’

(34) The teacher made Bill1 say that he1 hit his1 roommate.

a. The teacher made John2 say that he1 hit his1 roommate.

b. The teacher made John2 say that he2 hit his2 roommate.

c. *The teacher made John2 say that he2 hit his1 roommate.

d. *The teacher made John2 say that he1 hit his2 roommate.

The unavailability of any mix reading shows that the relevant null clausal

complement is an instance of deep anaphora. The following example confirms the

point:

(35) a. Sensei-ga Bill-ni [kare-no ruumumeito-ga kare -o nagutta to]

teacher-NOM Bill-DAT he-GEN roommate-NOM he-ACC hit

that

iw-ase-ta.

say-make-PAST

b. Sensei-wa John-ni-mo e iw-ase-ta.

teacher-TOP John-DAT-also say-make-PAST

‘The teacher made Bill say that his roommate hit him. The teacher made

John say e.’

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 181

Example (35b) does not allow the two mix readings given in (36), in a similar way to

(29).10

(36) The teacher made Bill1 say that his1 roommate hit him1.

a. The teacher made John2 say that his1 roommate hit him1.

b. The teacher made John2 say that his2 roommate hit him2.

c. *The teacher made John2 say that his2 roommate hit him1.

d. *The teacher made John2 say that his1 roommate hit him2.

3.2 No Extraction Out of the Null Clausal Complement in Japanese

The other argument against the CP-ellipsis approach comes from the fact that the null

clausal complement in Japanese does not allow extraction out of it, which is observed

by Shinohara (2006) and Tanaka (2008). The relevant example is given in (37), with

the analysis under the CP-ellipsis analysis.

(37) *Sono hon-o1

Taroo-wa Hanako-ga t1 katta to itta si, sono

that book-ACC Taroo-TOP Hanako-NOM bought that said and that

hon-o2

Ziroo-mo [Hanako-ga t2 katta

to] itta.

book-ACC Ziroo-also Hanako-NOM bought that said

‘Taroo said that Hanako bought that book, and Ziroo also said that she

bought that book.’

(Saito 2007:211)

10

Li (2002) observes that the null clausal complement in Chinese behaves like English VP ellipsis with

respect to the availability of mix interpretation, contrary to the Japanese null clausal complement. (i) allows

the mix reading in (iic) in the same way as (24a).

(i) John shuo-guo ta xihuan tade laoshi, Bill ye shuo-guo e.

his teacher Bill also say-ASP

John say-ASP he like

‘John said he liked his teacher; Bill also said e.’

(ii) a. John1

b. John1

c. John1

d. *John1

said he1 liked his1 teacher; Bill2 said

said he1 liked his1 teacher; Bill2 said

said he1 liked his1 teacher; Bill2 said

said he1 liked his1 teacher; Bill2 said

he1

he2

he2

he1

(Li 2002:161)

liked his1 teacher.

liked his2 teacher.

liked his1 teacher.

liked his2 teacher.

Example (iii) patterns with (24b) in the sense that it is four-ways ambiguous. The available interpretation is

given in (iv). Both of the mix readings are available.

(iii) John shuo-guo tade laoshi xihuan ta, Bill ye shuo-guo e.

him Bill also say-ASP

John say-ASP his teacher like

‘John said his teacher liked him; Bill said his teacher liked him.’

(iv) a.

b.

c.

d.

John1

John1

John1

John1

said

said

said

said

his1

his1

his1

his1

teacher

teacher

teacher

teacher

liked

liked

liked

liked

him1;

him1;

him1;

him1;

Bill2

Bill2

Bill2

Bill2

said

said

said

said

his1

his2

his2

his1

teacher

teacher

teacher

teacher

liked

liked

liked

liked

(Li 2002:162)

him1.

him2.

him1.

him2.

Li proposes that Chinese null object constructions are derived via VP ellipsis preceded by V-to-v raising,

which gives an explanation for the availability of mix interpretation above in a similar way to English VP

ellipsis. A detailed investigation of Chinese null object constructions is beyond the scope of this paper and

this interesting topic is left for future research. I thank a reviewer for bringing my attention to Li’s work.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

182 Hironobu Kasai

In (37), the scrambling of sono hon-o ‘that book-ACC’ takes place in both of the

conjuncts and the embedded CP is elided in the second conjunct. The ungrammaticality of (37a) has nothing to do with the fact that the scrambled phrases are not

contrastive. As shown in (38), even if the scrambled phrases are contrastive, the

example does not improve.

(38) *Hon-o1 Taroo-wa [Hanako-ga t1 katta to] itta ga,

zassi-o2

book-ACC Taroo-TOP Hanako-NOM bought that said though magazine-ACC

Ziroo-wa [Hanako-ga t2 katta

to] itta.

Ziroo-TOP Hanako-NOM bought that said

‘Taroo said that Hanako bought a book, but Ziroo said that she bought

a magazine.’

(Saito 2007:210)

The ungrammaticality of these examples is mysterious under the CP-ellipsis

approach. This is because it is widely observed that extraction can take place out

of ellipsis sites in principle, as shown here:11

(39) a. John knows which professor we invited, but he is not allowed to reveal

which one1 [we invited t1].

Sluicing

b. Mary doesn’t know who we can invite, but she can tell you who1 we can

not [invite t1].

VP ellipsis

c. This book, I know who bought; that one1, I don’t [know who bought t1].

VP ellipsis

In the previous subsections, I showed that the null clausal complement in Japanese

behaves like deep anaphora. Null-complement anaphora in English, which is

generally assumed to be an instance of deep anaphora, also disallows extraction out of

it, as shown here:

(40) a. *Bill knows which novel Bill volunteered to read and Mary knows which

bibliography Peter volunteered.

b. *Mary wondered which conference talk Tommy refused to attend and

Susan wondered which colloquium talk Susan refused.

c. *Susan asked Peter which house Anne agreed to donate and Mary asked

John which car Susan agreed.

(Depiante 2001:210)

As Hankamer & Sag (1976) argue, deep anaphora has no internal structure at syntax,

which readily explains the fact that nothing can move out of deep anaphora.

Pursuing the CP-ellipsis approach, Shinohara (2006) gives an explanation for the

question as to why nothing can move out of the null clausal complement. Saito (2007)

presents an updated version of Shinohara’s analysis, which is due to Kensuke Takita.

In what follows, I show that this updated version of her analysis cannot be

maintained.

11

Example (39c) is due to a reviewer.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 183

One of the important assumptions made in her analysis is that a long-distance

scrambled phrase undergoes reconstruction into its base position at LF (so-called

radical reconstruction), as independently argued by Saito (1989). Consider the

following examples:

(41) a. [Mary-ga [[John-ga dono-hon-o

tosyokan-kara karidasita] ka]

Mary-NOM John-NOM which book-ACC library-from checked-out Q

siritagatteiru] (koto).

want-to-know fact

‘(the fact that) Mary wants to know which book John checked out from

the library’

b. ?Dono-hon-o1

[Mary-ga [[John-ga tosyokan-kara t1 karidasita]

which book-ACC Mary-NOM John-NOM library-from

checked-out

ka] siritagatteiru] (koto).

Q want-to-know fact

(Saito 1989:191–192)

In (41b), dono-hon-o ‘which-book-ACC’ undergoes long distance scrambling and the

wh-phrase dono-hon-o is outside the scope of the Q-morpheme ka. Example (41b)

makes a sharp contrast with (42), where the wh-phrase is base-generated outside the

scope of ka.

(42) *John-ga dare-ni [[Mary-ga kuru] ka] osieta (koto)

John-NOM who-DAT Mary-NOM come Q taught fact

‘(the fact that) John told who Q Mary is coming’

(Saito 1989:190, originally due to Harada 1972)

The ungrammaticality of (42) falls under the general condition that wh-phrases have

to be contained within the CP where it takes scope at LF. Saito (1989) argues that the

grammaticality of (41b) shows that the long-distance-scrambled phrase can undergo

reconstruction into its base position at LF, which is within the scope of ka. Otherwise,

the wh-phrase could not be correctly interpreted similarly to (42).

Importantly, wh-movement in English does not exhibit radical reconstruction

effects, according to Saito (1989). Consider the following examples, which are due to

van Riemsdijk & Williams (1981):

(43) a.

[CP who1 [IP t1 wonders [CP [which picture of whom]2 [IP Bill bought

t2]]]]?

b. ??[CP [which picture of whom]2 does [IP John wonder [CP who1 [IP t1 bought

t2]]]]?

As van Riemsdijk & Williams note, whom in (43a) can be interpreted either at the

embedded clause or at the matrix clause. Nothing prevents whom from being

associated with the matrix C or the embedded C. In contrast, (43b), which is marginal

to begin with because it exhibits a wh-island effect, is not ambiguous. In (43b), whom

can be interpreted only at the matrix clause. The absence of the interpretation at the

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

184 Hironobu Kasai

embedded clause suggests that the wh-phrase is supposed to be interpreted outside the

scope of the embedded Q. If wh-movement could undergo radical reconstruction in

the same way as scrambling, the fronted wh-phrase could go back to its original

position at LF and there would be nothing wrong with interpreting whom at the

embedded clause.

Furthermore, the following example shows that radical reconstruction is obligatory,

not optional (see Tada 1990 for relevant discussion):

(44) *Dono hon-ni-mo1 [sono tyosya-ga [Hanako-ga t1 keti-o tuketa to]

which book-to-even its

author-NOM Hanako-NOM gave-criticism that

itta].

said

‘Every book1, its1 author said that Hanako criticized t1.’ (Saito 2003:486)

In (44), the long-distance-scrambled phrase dono hon-ni-mo ‘which book-to-even’

cannot license the bound pronoun in the matrix subject. The ungrammaticality of (44)

shows that the long-distance-scrambled phrase must go back to its original position at

LF.

Let us go back to Shinohara’s analysis. Shinohara tries to capture the

ungrammaticality of (37) and (38) under an LF-copying approach, proposed by

Chung, Ladusaw & McCloskey (1995). Let us take (38) as an example. Under

Shinohara’s analysis, the derivation of (38) is shown in (45).

(45) a. *[Hon-o1 Taroo-wa [Hanako-ga t1 katta to] itta] ga, zassi-o Ziroo-wa e itta.

Step 1: Reconstruction of the scrambled phrase

b. [Taroo-wa [Hanako-ga hon-o katta to] itta] ga, zassi-o Ziroo-wa e itta.

Step 2: LF copying of the embedded CP

c. [Taroo-wa [Hanako-ga hon-o katta to] itta] ga, zassi-o Ziroo-wa [Hanako-ga

hon-o katta to] itta.

The scrambled phrase hon-o ‘book-ACC’ is reconstructed into the base position in

(45a). Then the embedded CP is copied into the second conjunct in (45b). The

representation given in (45c) is finally obtained. The scrambled phrase in the second

conjunct zassi-o ‘magazine-ACC’ cannot form a chain because the copied CP involves

a distinct object hon-o ‘book’ in the object position. The important point of

Shinohara’s analysis is that the relevant unextractability out of the ellipsis site is

reduced to the radical reconstruction property of Japanese scrambling.

On the other hand, there is nothing wrong with (39). Let us take (39a) as an

example. Recall from the discussion in (43) that wh-movement does not exhibit

radical reconstruction effects. What undergoes LF copying includes a trace to be

bound by a wh-phrase, as shown in (46).

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 185

(46) John knows which professor [TP we invited t], but he is not allowed to reveal which one1 e

LF copying

The trace within the copied material forms a chain with the wh-phrase in the second

conjunct. Thus, the legitimate interpretation is obtained.

However, the analysis faces a difficulty of dealing with scrambling out of an

infinitival clause, which is not subject to radical reconstruction. Nemoto (1993)

observes that scrambling out of an infinitival clause behaves like A-movement in the

sense that the scrambled phrase is capable of binding a bound pronoun. The relevant

example is given here:

(47) ?Dare-o1 soitu1-no hahaoya-ga Michael-ni [PRO t1 kubinisuru yoo(ni)]

who-ACC he-GEN

mother-NOM Michael-DAT

fire

Comp

tanonda no?

asked Q

‘Who1 does his1 mother asked Michael to fire?’

(Nemoto 1993:45)

The scrambled phrase out of the infinitival clause does not have to be reconstructed

but rather has to be interpreted in the scrambled position. It is expected that

scrambling out of the infinitival clause would not face the problem shown in (45).

The extraction should be allowed, but this expectation is not borne out. As shown in

(48), scrambling cannot take place out of the null infinitival clause, either.

(48) *Tokyo-ni3 Hanako-wa Taroo-ni1 [PRO1 t3 iku-yooni] meizita. Kyoto-ni4

Tokyo-DAT Hanako-TOP Taroo-DAT

go-Comp ordered Kyoto-DAT

Sachiko-wa Ziroo-ni2 [PRO2 t4 iku-yooni] meizita.

Sachiko-TOP Ziroo-DAT

go-Comp ordered

‘Hanako ordered Taroo to go to Tokyo. Sachiko ordered Ziroo to go to Kyoto.’

The ungrammaticality of (48) is due to the scrambling out of the elided clause. There

is nothing wrong with omitting the infinitival clause, as shown in (49).

(49) Hanako-wa Taroo-ni1 [PRO1 Tokyo-ni iku-yooni] meizita. Hanako-wa

Hanako-TOP Taroo-DAT

Tokyo-DAT go-Comp ordered Hanako-TOP

Ziroo-ni-mo e meizita.

Ziroo-DAT-also ordered

‘Hanako ordered Taroo to go to Tokyo. Hanako ordered Ziroo e, too.’

Contrary to Shinohara’s analysis, if the null clausal complement under investigation

behaves like deep anaphora, then the unextractability is simply reducible to the

absence of syntactic structure within deep anaphora.

To sum up, the absence of mix readings and the unextractability out of the null

clausal complement show that the clausal complement in Japanese is not allowed to

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

186 Hironobu Kasai

undergo ellipsis. Otherwise, the relevant mix readings would be available and

extraction could take place out of the null clausal complement, contrary to fact.

4. Concluding Remarks

It has been argued that the null clausal complement in Japanese does not involve

ellipsis but is analyzed as pro. The availability of sloppy interpretation in the null

clausal complement does not necessarily support the CP-ellipsis approach, because

not only surface anaphora but also deep anaphora allows sloppy interpretation.

Rather, the sloppy interpretation found in the relevant construction patterns along

with that in deep anaphora such as pro in the sense that the use of an a-occurrence in

place of a b-occurrence as a bindee does not affect the availability of sloppy readings.

The absence of mix readings and the unextractability out of the null clausal

complement also support the proposed analysis.

Before I conclude, I should touch on one remaining issue. As argued in section 2,

the availability of sloppy interpretation is not a compelling piece of evidence for the

argument ellipsis approach. However, it has been reported that there are independent

pieces of evidence for it apart from the availability of sloppy interpretation; one of

these is given in (50).

(50) a. Speaker A: Dare-ga zibun-o hihansimasita ka?

who-NOM self-ACC criticized

Q

‘Who criticized himself?’

b. Speaker B: Taroo1/daremo1-ga e1 hihansimasita.

Taroo/everyone-NOM criticized

‘Taroo/everyone criticized e.’

(Takahashi 2008b:309)

If the null argument in (50b) were an empty pronoun, (50b) would violate binding

condition B. On the other hand, the ellipsis approach captures (50b), by saying that

zibun-o ‘self-ACC’ undergoes ellipsis.

If the argument based on (50) is on the right track, it is necessary to postulate the

ellipsis strategy for null nominal arguments in Japanese, in addition to the pro

strategy. This raises one question as to why nominal arguments can undergo ellipsis,

unlike clausal complements in Japanese. In other words, why does the asymmetry

exist between nominal arguments and clausal arguments with respect to the

applicability of ellipsis? This issue must be left for future research.

References

B€

uring, D. 2004. Crossover situations. Natural Language Semantics 12:23–62.

Chung, S., W. Ladusaw & J. McCloskey. 1995. Sluicing and logical form. Natural Language

Semantics 3:239–282.

Cooper, R. 1979. The interpretation of pronouns. In Selections from the third Groningen Round

Table [Syntax and Semantics 10], ed. F. Heny & H. Schnelle, 61–92. New York: Academic

Press.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

On the Nature of Null Clausal Complements in Japanese 187

€ 1974. How to open a sentence: Abstraction in natural language. Technical report,

Dahl, O.

University of G€oteberg, Logical grammar reports 12.

Dalrymple, M. 1991. Against reconstruction in ellipsis. Xerox Technical Report, Xerox-PARC,

Palo Alto, CA.

Dalrymple, M., S. Shieber & F. Pereira. 1991. Ellipsis and higher-order unification. Linguistics

and Philosophy 14:399–452.

Depiante, M. A. 2001. On null complement anaphora in Spanish and Italian. Probus 13:193–221.

Elbourne, P. 2005. Situations and individuals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Engdahl, E. 1986. Constituent questions. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Fiengo, R. & R. May. 1994. Indices and identity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fukaya, T. & H. Hoji. 1999. Stripping and sluicing in Japanese and some implications. In

Proceedings of the 18th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, ed. S. Bird, A.

Carnie, J. D. Haugen & P. Norquest, 145–158. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Hankamer, J. & I. A. Sag. 1976. Deep and surface anaphora. Linguistic Inquiry 7:391–426.

Harada, K.I. 1972. Constraints on wh-Q binding. In Studies in descriptive and applied

linguistics 5:180–206. Tokyo: Division of Languages, International Christian University.

Hasegawa, N. 1985. On the so-called “zero pronouns” in Japanese. The Linguistic Review

4:289–342.

Hoji, H. 1985. Logical form constraints and configurational structures in Japanese. Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle.

Hoji, H. 1991. Kare. In Interdisciplinary approaches to language: In honor of Prof. S.-Y.

Kuroda, ed. R. Ishihara & C. Georgopoulos, 287–304. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hoji, H. 1995. Demonstrative binding and principle B. In Proceedings of the 25th annual

meeting of the North East Linguistic Society, ed. J. N. Beckman, 255–271. Amherst, MA:

GLSA Publications.

Hoji, H. 1998. Null object and sloppy identity in Japanese. Linguistic Inquiry 29:127–152.

Hoji, H. 2003. Surface and deep anaphora, sloppy identity, and experiments in syntax. In

Anaphora: A reference guide, ed. A. Barss, 172–236. Oxford: Blackwell.

Huang, C.-T. J. 1984. On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry

15:531–574.

Huang, C.-T. J. 1988. Comments on Hasegawa’s paper. In Proceedings of Japanese syntax

workshop: Issues on empty categories, ed. T. Wako & M. Nakayama, 77–93. New London:

Connecticut College.

Huang, C.-T. J. 1991. Remarks on the status of the null object. In Principles and parameters in

comparative grammar, ed. R. Freidin, 56–76. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ishii, Y. 1991. Operators and empty categories in Japanese. Ph.D. dissertation, University of

Connecticut, Storrs.

Jacobson, P. 2000. Paycheck pronouns, Bach-Peters sentences, and variable-free semantics.

Natural Language Semantics 8:77–155.

Karttunen, L. 1969. Pronouns and variables. In Papers from the fifth regional meeting of the

Chicago Linguistic Society, 108–116. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Kennedy, C. & J. Merchant. 2000. The case of the “missing CP” and the secret case. In The

Jorge Hankamer WebFest, ed. C. Sandra, J. McCloskey & N. Sanders. Santa Cruz:

University of California, Santa Cruz. Available at: http://ling.ucsc.edu/Jorge/index.html.

Kim, S.-W. 1999. Sloppy/strict identity, empty objects, and NP ellipsis. Journal of East Asian

Linguistics 8:255–284.

Kuroda, S.-Y. 1965. Generative grammatical studies in the Japanese language. Ph.D.

dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Lasnik, H. 1976. Remarks on coreference. Linguistic Analysis 2:1–22.

Li, H.-J.G. 2002. Ellipsis constructions in Chinese. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern

California, Los Angeles.

Nemoto, N. 1993. Chains and case positions: A study from scrambling in Japanese. Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Connecticut, Storrs.

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

188 Hironobu Kasai

Ohso, M. 1976. A study of zero pronominalization in Japanese. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State

University, Columbus.

Oku, S. 1998. A theory of selection and reconstruction in the minimalist perspective. Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Otani, K. & J. Whitman. 1991. V-raising and VP-ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 22:345–358.

van Riemsdijk, H. & E. Williams. 1981. NP-structure. The Linguistic Review 1:171–217.

Reinhart, T. 1983. Anaphora and semantic interpretation. London: Croom Helm.

Sag, I.A. 1976. Deletion and logical form. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Saito, M. 1985. Some asymmetries in Japanese and their theoretical implications. Ph.D.

dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Saito, M. 1989. Scrambling as semantically vacuous A-bar movement. In Alternative

conceptions of phrase structure, ed. M. Baltin & A. Kroch, 182–200. Chicago: University of

Chicago Press.

Saito, M. 2003. A derivational approach to the interpretation of scrambling chains. Lingua

113:481–518.

Saito, M. 2004. Ellipsis and pronominal reference in Japanese clefts. Nanzan Linguistics 1:21–50.

Nagoya Japan: Center for Linguistics, Nanzan University.

Saito, M. 2007. Notes on East Asian argument ellipsis. Language Research 43:203–227.

Shinohara, M. 2006. On some differences between the major deletion phenomena and Japanese

argument ellipsis. Ms., Nanzan University, Nagoya, Japan.

Tada, H. 1990. Scrambling(s). Ms., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Takahashi, D. 1994. Sluicing in Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 3:265–300.

Takahashi, D. 2006. Apparent parasitic gaps and null arguments in Japanese. Journal of East

Asian Linguistics 15:1–35.

Takahashi, D. 2008a. Noun phrase ellipsis. In The Oxford handbook of Japanese linguistics,

ed. S. Miyagawa & M. Saito, 394–422. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Takahashi, D. 2008b. Quantificational null objects and argument ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry

39:307–326.

Tanaka, H. 2008. Clausal complement ellipsis. Ms., University of York, Heslington, York, UK.

Available at: http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~ht6/CCE.pdf.

Tomioka, S. 1999. A sloppy identity puzzle. Natural Language Semantics 7:217–241.

Wescoat, M. 1989. Sloppy readings with embedded antecedents, Ms., Stanford University,

Palo Alto, CA.

Williams, E. S. 1977. Discourse and logical form. Linguistic Inquiry 8:101–139.

Zushi, M. 2003. Null arguments: The case of Japanese and Romance. Lingua 113:559–604.

Hironobu Kasai

University of Kitakyushu

Center for Fundamental Education

4-2-1 Kitagata Kokuraminamiku

Kitakyushuu

Fukuoka 802-8577

Japan

kasai@kitakyu-u.ac.jp

© 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd