UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY

advertisement

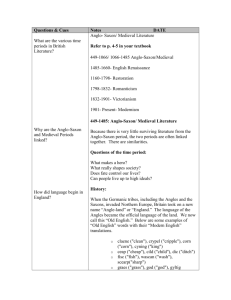

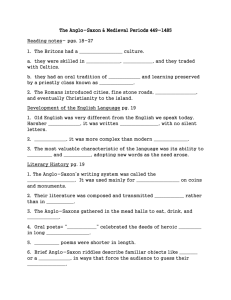

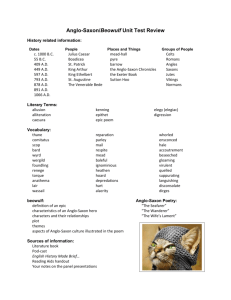

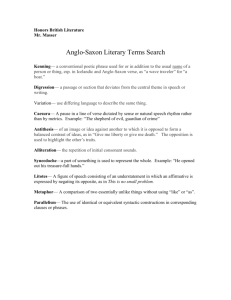

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCLG004 Medieval Archaeology: Select Topics and Current Problems 2014/15 Masters Option, 30 Credits Turnitin Class ID: 2969773 Turnitin Password: IoA1516 Co-ordinator: Professor Andrew Reynolds a.reynolds@ucl.ac.uk 020 7679 1522 Room 205 Please see the last page of this document for important information about submission and marking procedures, or links to the relevant webpages. OVERVIEW Short description This course considers a number of key topics relating to the study of Anglo-Saxon and medieval England and its neighbours, focusing on the period AD400-1200. The course is divided into two parts. Part One considers the development of rural settlement from the postRoman period to the landscape of the Domesday Survey and after, and moves on to consider craft production, trade and the emergence of towns. Part Two aims to provide a detailed examination of traditions of burial and religion during the period and to examine processes such as the conversion to Christianity and its effect on the archaeological record. A landscape perspective rounds off the course with a focus on warfare and social organization. Each student will be expected to prepare and deliver seminar papers on relevant subjects of their choice. Particular emphasis is placed on interdisciplinary approaches to the medieval period using place-names, documents and archaeology. Week-by-week summary Autumn Term 1. Tuesday 30th September 2. Tuesday 7th October 3. Tuesday 14th October 4. Tuesday 21st October 5. Tuesday 28th October Introduction to the Study of Medieval Archaeology AR Documents and medieval archaeology AR Early Anglo-Saxon Rural Settlement CS Later Anglo-Saxon Rural Settlement AR Early Medieval Wales RC READING WEEK 3rd-7th November 6. Tuesday 11th November 7. Tuesday 18th November 8. Tuesday 25th November 9. Tuesday 2nd December 10. Tuesday 9th December Anglo-Saxon Economics GW Anglo-Saxon Charters and Archaeology AR Landscapes of Warfare TW Political and Administrative Landscapes AR Student Presentations AR Spring Term 11. Tuesday 13th January 12. Tuesday 20th January 13. Tuesday 27th January Cremation SH Inhumation SH The Geography of Anglo-Saxon Burial AR 1 14. Tuesday 3rd February 15. Tuesday 10th February The ‘Final Phase’ CS The Conversion to Christianity in Britain BY READING WEEK 16th-20th February 16. Tuesday 24th February 17. Tuesday 3rd March 18. Tuesday 10th March 19. Tuesday 17th March 20. Tuesday 24th March Basic texts W. Davies, S. Foster, C. Hills, A. Reynolds, M. Welch, Art and Society in Anglo-Saxon England, c. 600-1100 JK Viking Settlement JK Anglo-Saxon and Medieval London: Continuity and Change JC Student Presentations and Course Review AR Visit to the British Museum AR Wales in the Early Middle Ages (1982) [HISTORY 26f DAV] Picts, Scots and Gaels (1996) [DAA 500 FOS] Early Historic Britain, in The Archaeology of Britain, ed. J. Hunter & I. Ralston (1998), 176-93 [DAA 100 HUN] Later Anglo-Saxon England: Life & Landscape (1999) [DAA 180 REY] Anglo-Saxon England (1992/ reprinted 2000) [DAA 180 WEL] Methods of assessment This course is assessed by means of two essays of between 3800-4200 words, each of equal weight in their contribution to the overall mark. Teaching methods One weekly two-hour session will form the main method of teaching. Students are provided with a reading list for each seminar (see below). Each seminar will be opened with a short presentation by the teacher to be followed by a detailed consideration of the topic in hand by students. Seminars have weekly compulsory readings, which students will be expected to have covered, to be able fully to follow and actively to contribute to discussion. In addition, a visit to the early medieval gallery at the British Museum will take place on Tuesday 24th March between 4-6pm to give students greater familiarity with the material covered in the course. Students will be required to give one individual presentation during the course, either at the end of Term I or at the End of Term II. Student seminar topics, which may be based on a theme chosen for one of the written assignments of the course, will be arranged well in advance by agreement with Professor Reynolds. Workload There will be 38 hours of seminars/lectures and 2 hours at the British Museum for this course. Students will be expected to undertake around 250 hours of reading for the course, 60 hours preparing for and producing the assessed work. This adds up to a total workload of some 350 hours for the course. Prerequisites This course does not have a prerequisite, however, if students have no previous background in medieval archaeology, it would be advisable for them also to attend (but not be assessed for) the undergraduate course ARCL2018 Early Medieval Archaeology of Britain (Professor Reynolds: Thursdays 4-6 in Room 209) to ensure that they have the background to get the most out of the Masters level seminars in this course. AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND ASSESSMENT 2 Aims This course seeks to introduce students to aspects of the archaeology of early medieval Britain during the period AD400-1200. The introductory sessions will provide a critical interdisciplinary overview of the period in question introducing the main contemporary topics and debates. Students will then examine a series of key topics in detail to provide them with an advanced knowledge of the period. Students will develop key skills in the interdisciplinary study of the past, while the period itself provides a well-defined case study of the emergence of social complexity in post-Empire societies. Objectives On successful completion of this course a student should have an overview of the development of the English landscape over a long and complex period. Students should understand the nature of documentary evidence and its role in medieval archaeology and be able to critically assess aspects of historical narrative using archaeological evidence. Students should be able to apply a wide range of source materials and techniques to approach individual topics and themes and be familiar with the principal research resources for the period. Learning outcomes On successful completion of the course students should be able to demonstrate/have developed the ability to identify and examine specific problems using varied evidence. Preparation and delivery of individual student presentations should ensure the application of acquired knowledge and the development of oral presentation skills, whilst participation in both staff and student led seminars will enhance critical observation and reflection. Coursework Essay topics will be determined on an individual basis by agreement with the Course Coordinator. Students are not permitted to re-write and re-submit essays in order to try to improve their marks. However, if students are unclear about the nature of an assignment, they should contact the Course Co-ordinator who will also be willing to discuss an outline of an assignment provided this is planned suitably in advance of the submission date. Deadlines for each assignment are: Essay 1 – Friday 28th November 2014 Essay 2 – Friday 6th March 2015 Essays should be within the range of 3800-4200 words. The following should not be included in the word-count: title page, contents pages, lists of figure and tables, abstract, preface, acknowledgements, bibliography, lists of references, captions and contents of tables and figures, appendices. Penalties will only be imposed if you exceed the upper figure in the range. There is no penalty for using fewer words than the lower figure in the range: the lower figure is simply for your guidance to indicate the sort of length that is expected. SCHEDULE AND SYLLABUS Teaching schedule Seminars will be held 4-6pm on Thursdays in Room 209 at the Institute of Archaeology. A visit to the British Museum early medieval gallery is scheduled for Tuesday 24th March between 4-6pm, meeting in the gallery Room 41. The course will be taught be Professor Andrew Reynolds (AR), with guest seminars by Dr Stuart Brookes (SB), John Clark, 3 Rhiannon Comeau, Dr Sue Harrington (SH), Dr Jane Kershaw (JK), Professor Chris Scull (SC), Dr Gareth Williams (GW), Tom Williams (TW) and Professor Barbara Yorke (BY). SYLLABUS The following is an outline for the course as a whole, and identifies essential and supplementary readings relevant to each session. Information is provided as to where in the UCL library system individual readings are available; their location and Teaching Collection (TC) number, and status (whether out on loan) can also be accessed on the eUCLid computer catalogue system. Readings marked with an * are considered essential to keep up with the topics covered in the course. Copies of individual articles and chapters identified as essential reading are in the Teaching Collection in the Institute Library (where permitted by copyright) or are available online. 1. Introduction to the Study of Medieval Archaeology AR This session outlines the structure and organisation of the course and the nature of the written work required for its successful completion. You might find it useful to gain an insight into the development of medieval archaeology as a discipline by reference to the following publications, each of which provides a broad reflection on the priorities of the subject at the time they were published: D. Austin and L. Alcock (eds) 1990 From the Baltic to the Black Sea: Studies in Medieval Archaeology. London: Routledge (esp. Ch. 1 by D. Austin) [INST ARCH DA 190 AUS] C. Gerrard 2003 Medieval Archaeology: Understanding Traditions and Contemporary Approaches. London: Routledge [INST ARCH DAA 190 GER] R. Gilchrist and A. Reynolds (eds) Reflections: 50 Years of Medieval Archaeology, 19572007. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 30 (wide selection of Europewide overviews) [INST ARCH DA 190 GIL] D. Hinton (ed.), 1983 25 Years of Medieval Archaeology. Sheffield: University of Sheffield [INST ARCH DAA 190 HIN] D. Hinton 1987 ‘Archaeology and the Middle Ages. Recommendations by the Society for Medieval Archaeology to the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England’, Medieval Archaeology 31, 1-12 [INST ARCH PERS] Do follow up any references or topics you think might be of value to the seminar – you will be expected to contribute fully at each meeting. 2. Documents and medieval archaeology AR This session explores the relationship between written sources and archaeological evidence through a series of case studies. Written sources to be considered include Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Beowulf and Anglo-Saxon charters. Medieval archaeology has been criticised for its over-reliance on written sources to provide an explanatory framework for the period and the session also examines the tensions between historians and archaeologists. Essential J. Moreland 2001 Archaeology and Text. London: Duckworth. [INST ARCH AH MOR] Texts M. Alexander 1981 Beowulf: a verse translation. [MAIN LITERATURE F 21:40 BEO] 4 S. Bradley 1995 Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: J.M. Dent. [INST ARCH DAA 180 BRA; MAIN ENGLISH D20 BRA] B. Colgrave and R. Mynors (eds) 1969 Bede’s Ecclesiatical History of the English People. Harmondsworth: Penguin.[MAIN HISTORY 27 h BED] D. Douglas and G. Greenaway (eds) 1981 English Historical Documents Volume 2, 10421189. Oxford: Eyre Methuen. [MAIN HISTORY 5 a ENG 2] M. Godden and M. Lapidge (eds) 1991 The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [MAIN ENGLISH D 5 GOD] P. Sawyer 1968 Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated List and Bibliography. London: Royal Historical Society. [INST ARCH DAA 180 SAW] M. Swanton (ed.) 2000 The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. London: J.M. Dent. [HISTORY 6 d SAW] D. Whitelock 1979 English Historical Documents Volume 1, c.500-1042. Oxford: Eyre Methuen.[INST ARCH DAA 180 SAW; MAIN ENGLISH D 140 SAW] Case studies R. Cramp ‘Beowulf and Archaeology’, Medieval Archaeology 1, 57-78 [INST ARCH PERS] A. Reynolds ‘Burials, boundaries and charters in Anglo-Saxon England: A Reassessment’, in E. Leeds 1936 Early Anglo-Saxon Art and Archaeology. Oxford: Clarendon Press. (esp. Chapters 1 and 2) [INST ARCH DAA 180 LEE] S. Lucy and A. Reynolds (eds), Burial in Early Medieval England and Wales. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 17, 171-94. [INST ARCH DAA 180 LUC] 3. Early Anglo-Saxon rural settlement and economy CS This session examines the archaeological evidence for rural settlement and its social dimensions in eastern and southern England from the 5th to the 7th centuries. Building types and traditions, settlement configurations and evidence for the economic base all provide insights into past lifeways and communities but critical aspects of settlement character and development are contested and debated. Was rural settlement shifting or stable? Were these farmsteads or village communities? Is there evidence for settlement hierarchy before the 7th century? Essential H. Hamerow 2012 Rural Settlements and Society in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: OUP (available online) INST ARCH DAA 180 HAM Some Key Studies and Sites M. Bell 1977 ‘Excavations at Bishopstone in Sussex: the Anglo-Saxon period’, Sussex Archaeological Collections 115, 193-241 [INST ARCH PERS] R. Chambers and E. McAdam 2007 Excavations at Barrow Hills, Radley, Oxfordshire, 19835. Volume 2: the Romano-British Cemetery and Anglo-Saxon Settlement. Oxford: Oxford Archaeology. INST ARCH DAA 410 Qto CHA R. Cowie and L. Blackmore 2008, Early and Middle Saxon Rural Settlement in the London Region. London: MoLAS. INST ARCH DAA 416 Qto COW P. Crabtree 2012 Middle Saxon Animal Husbandry in East Anglia. East Anglian Archaeology Report 143. Especially Chapters 2, 4 and 6. INST ARCH DAA Qto Series EAA 143 5 P. Fowler 2002 Farming in the First Millennium AD: British Agriculture between Julius Caesar and William the Conqueror. Cambridge: CUP. INST ARCH DAA 100 FOW H. Hamerow 1993 Excavations at Mucking, Vol. 2: The Anglo-Saxon Settlement. London: English Heritage. INST ARCH DAA 410 Qto CLA H. Hamerow 2006 ‘“Special deposits” in Anglo-Saxon settlements’, Medieval Archaeology 50, 1-30. (available online) INST ARCH PERS S. James, A. Marshall and M. Millett 1984 ‘An early medieval building tradition’, Archaeological Journal, 141, 182-215. INST ARCH PERS S. Losco-Bradley and G. Kinsley 2002 Catholme: an Anglo-Saxon Settlement on the Trent Gravels in Staffordshire. Nottingham: Nottingham University. INST ARCH DAA 410 Qto LOS S. Lucy, J. Tipper and A. Dickens 2009 The Anglo-Saxon Settlement and Cemetery at Bloodmoor Hill, Carlton Colville, Suffolk. East Anglian Archaeology Report 131. INST ARCH DAA Qto Series EAA 131 M. Millett and S. James 1983 ‘Excavations at Cowdery’s Down, Basingstoke, Hampshire 1978–81’, Archaeological Journal 140, 151-279. INST ARCH PERS J. Morris and B. Jervis 2011 ‘What’s so special? A reinterpretation of Anglo-Saxon “special deposits”’, Medieval Archaeology 55, 66-81. (available online) INST ARCH PERS Powlesland, D. 1997 ‘Early Anglo-Saxon settlements, structures, form and layout’ in J. Hines (ed) The Anglo-Saxons from the Migration period to the Eighth Century: an Ethnographic Perspective, 101-124. Woodbridge: Boydell. INST ARCH DAA 180 HIN; ISSUE DESK IOA HIN 4 A. Reynolds 2003 ‘Boundaries and settlements in later sixth to eleventh century England’, Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 12, 98-136. INST ARCH DAA 180 ANG J. Tipper 2004 The Grubenhaus in Anglo-Saxon England. Yedingham: Landscape Research Centre. INST ARCH DAA 180 Qto TIP S. West 1985 West Stow: The Anglo-Saxon Village. East Anglian Archaeology Report 24. INST ARCH DAA Qto Series EAA 24 B. Hope-Taylor 1977 Yeavering: An Anglo-British Centre of Early Northumbria. London: HMSO. INST ARCH DAA 410 N. 7 HOP Do follow up any references or topics you think might be of value to the seminar – you will be expected to contribute fully at each meeting. 4. Late Anglo-Saxon Rural Settlement AR This session considers the emergence of the landscape of the Domesday Survey and the pattern of settlement that determines the modern landscape. Particular issues for discussion include the origins of territorial units (estates, hundreds etc) and of the manor, and whether the process of settlement during this period is best understood using simple or complex models. Essential G. Beresford 1987 Goltho: The Development of an Early Medieval Manor c.850-1150 [ISSUE DESK IOA BER 1; INST ARCH DAA 410 L.6 BER] D. Hooke 1998 The Landscape of Anglo-Saxon England. (Chapter 3) INST ARCH DAA 180 HOO A. Reynolds 1999 Later Anglo-Saxon England: Life & Landscape (chapter 4, 111-157) [ISSUE DESK IOA DAA 180 REY; INST ARCH DAA 180 REY] G. Thomas 2010 The later Anglo-Saxon settlement at Bishopstone: a downland manor in the making. INST ARCH DAA Qto Series COU 163 6 Recommended reading J. Blair 1993 ‘Hall and chamber: English domestic planning 1000-1250’, in G. Meirion-Jones & M. Jones, Manorial Domestic Buildings in England and Northern France [INST ARCH DAA 300 MEI] J. Blair 1996 ‘Palaces or Minsters? Northampton and Cheddar reconsidered’, Anglo-Saxon England 25, 97-121 [INST ARCH PERS] B.K. Davison 1977 ‘Excavations at Sulgrave, Northamptonshire, 1960-76’, Archaeological Journal 134, 105-14 [INST ARCH PERS] D. Hooke 1988 Anglo-Saxon Settlements (esp. Introduction, 1-8) [ISSUE DESK IOA HOO 1] C. Lewis, P. Mitchell-Fox and C. Dyer 1997 Village, hamlet and field [INST ARCH DAA 190 LEW] C. Loveluck 1998 ‘A high-status Anglo-Saxon settlement at Flixborough, Lincolnshire’, Antiquity 72, 146-61 [INST ARCH PERS] P.A. Rahtz 1976 The Saxon and Medieval palaces at Cheddar [INST ARCH DAA QTO SERIES BRI 65] A. Reynolds 2002 Boundaries and settlements in later 6th to 11th century England, AngloSaxon Studies in Archaeology and History 12, 97-136 [INST ARCH DAA 180 ANG] A. Williams 1986 “A bell-house and burhgeat”: lordly residence in England before the Norman Conquest, in C. Harper-Bill & R. Harvey, The Ideals and Practice of Medieval Knighthood, 221-40 [HISTORY 82 cu IDE] B. Yorke 1995 Wessex in the Early Middle Ages (esp. 243-55) [INST ARCH DAA 180 YOR; ISSUE DESK IOA YOR] 5. Early Medieval Wales RC The existing understanding of early medieval Wales is very limited compared, for instance, to Anglo-Saxon England and this session will consider why this is and what impact it has. Using maps, written sources and place-names, we will also explore how a multidisciplinary approach can provide insight into one under-researched area, the pre-Conquest Welsh landscape. Essential Davies, W. 2004: Looking backwards to the early medieval past: Wales and England, a contrast in approaches. Welsh History Review, 22 (2), 197 – 221 (UCL Journals online) Edwards, N., Lane, A. & Redknap, M. 2011: Early Medieval Wales: An updated Framework for Archaeological Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales. Available at: http://www.archaeoleg.org.uk/pdf/earlymed2011.pdf . (NB – this is a revision of an earlier document which can be found, with comprehensive bibliographies, at: http://www.archaeoleg.org.uk/earlymed.html.) Jones, G. R. J. 1985: Forms and Patterns of Medieval Settlements in Welsh Wales. In: Hooke, D. (ed.) Medieval Villages: a review of current work. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology, 155-170 (book chapter) INST ARCH DAA 190 HOO Recommended reading Austin, D. 2005: Little England Beyond Wales: Re-defining the Myth. Landscapes 6(2), 3062. (UCL Journals online) Bollard, J. K. 2009: Landscapes of the Mabinogi. Landscapes 10(2), 37-60 (UCL Journals online) Campbell, E. & Lane, A. 1993: Excavations at Longbury Bank, Dyfed, and early medieval settlement in south Wales. Medieval Archaeology 37, 15-77 (UCL Journals online) 7 Comeau, R. 2012: From Tref(gordd) to Tithe: Identifying Settlement Patterns in a North Pembrokeshire Parish. Landscape History 33(1), 29-44 (UCL Journals online) Davidson, A. & Silvester, B. 2013: A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales: Medieval. Available at: http://www.archaeoleg.org.uk/pdf/med/medieval.pdf (NB – this is a revision of an earlier document which can be found, with comprehensive bibliographies, at: http://www.archaeoleg.org.uk/med.html) Edwards, N. 2001: Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales - Context and Function. Medieval Archaeology XLV, 15-40 (UCL Journals online) Longley, D. 2001: Medieval settlement and landscape on Anglesey. Landscape History 23, 39-59. (UCL Journals online) Seaman, A. 2010: Towards a Predictive Model of Early Medieval Settlement Location: A Case Study from the Vale of Glamorgan. Medieval Settlement Research, 25, 12-22. (available at: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/msrg_2012/volumes.cfm) Seaman, A. 2013: Dinas Powys in Context: Settlement and Society in Post- Roman Wales. Studia Celtica 47, 1-23. (UCL Journals online) Thomas, C. 1980: Place-names studies and agrarian colonization in North Wales. Welsh History Review, 10(2), 155-171 (available online at http://welshjournals.llgc.org.uk/browse/listissues/llgc-id:1073091) More reading: see the comprehensive bibliographies listed at http://www.archaeoleg.org.uk/theme.html. The following books and articles give a flavour of research: Campbell, E. 2007: Continental and Mediterranean Imports to Atlantic Britain and Ireland, AD 400-800. CBA Research Report 157 York: CBA. INST ARCH DAA Qto Series COU 157 Charles-Edwards, T. M. 2013: Wales and the Britons 350-1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press. HISTORY 26 F CHA (and also online access via UCL Library Catalogue/ Oxford Scholarship Online) Comeau, R. (forthcoming Autumn 2014): Bayvil in Cemais: a pre-Norman assembly site in West Wales? Medieval Archaeology, 58, 282-298 (UCL Journals online) Davies, W. A. 2001: Thinking about the Welsh environment a thousand years ago. In: Jenkins , G. (ed.) Cymru a’r Cymry 2000. Wales and the Welsh 2000. Aberystwyth: Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies.1-18 . Reprinted in Davies, W. 2009: Welsh History in the Early Middle Ages: Texts and Societies, Farnham: Ashgate. HISTORY 26 F DAV Edwards, N. & Lane, A. (eds.) 1992: The Early Church in Wales and the West. Oxford: Oxbow. INST ARCH DAA 169 Qto EDW Edwards, N. (ed.) 1997: Landscape and settlement in medieval Wales. Oxford: Oxbow INST ARCH DAA 600 Qto EDW Edwards, N. (ed.) 2009: The Archaeology of the Early Medieval Celtic Churches. Leeds: Maney. INST ARCH DAA 190 EDW Edwards, N. 2007: A Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales, Volume II., Cardiff: University of Wales Press INST ARCH DAA 600 COR Edwards, N. 2009: Rethinking the pillar of Eliseg. Antiquaries Journal, 89, 143-77 (UCL Journals online) Edwards, N. 2013: A Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales, Volume III. North Wales, Cardiff, University of Wales Press. INST ARCH DAA 600 COR Griffiths, D. 2003: Markets and 'Productive' Sites: a View from Western Britain. In: Pestell, T. & Ulmschneider, K. (eds.) Markets in Early Medieval Europe. Macclesfield: Windgather Press. 62-72 INST ARCH DA 180 PES 8 Griffiths, D. 2009: Sand-dunes and Stray Finds: Evidence for Pre-Viking trade? In: GrahamCampbell, J. & Ryan, M. (eds.) Anglo-Saxon/Irish Relations before the Vikings. Proceedings of the British Academy, 157. Oxford: OUP/British Academy, 265-280 HISTORY 27 H GRA Jones, G. R. J. 2012: Britons, Saxons, and Scandinavians : the historical geography of Glanville R.J. Jones, Turnhout: Brepols INST ARCH DAA 100 JON Redknap, M. & Lewis, J. M. (eds.) 2007: A Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones and Stone Sculpture in Wales Volume I, Cardiff: University of Wales Press. INST ARCH DAA 600 COR Redknap, M. 2010: The Vikings in Wales. In: Brink, S. & Price, N. (eds.) The Viking World. London: Routledge.401-410 INST ARCH DA 181 BRI Redknap, M. 2009: Glitter in the Dragon's Lair: Irish and Anglo-Saxon Metalwork from PreViking Wales. In: Graham-Campbell, J. & Ryan, M. (eds.) Anglo-Saxon/Irish Relations before the Vikings. Proceedings of the British Academy, 157. Oxford: OUP/British Academy 281-309 HISTORY 27 H GRA Seaman, A. 2012: The Multiple Estate Model Reconsidered: Power and Territory in Early Medieval Wales. The Welsh History Review 26, 163-185. (UCL Journals online) Silvester, B. & Kissock, J. 2012: Wales: Medieval Settlements, Nucleated and Dispersed, Permanent and Seasonal. In: Christie, N. & Stamper, P. (eds.) Medieval Rural Settlement: Britian and Ireland, AD 800-1600. Oxford: Windgather Press. 151-171 INST ARCH DAA 190 CHR Wickham, C. 2010: Medieval Wales and European History. Welsh History Review, 25, 201-8. (UCL Journals online) Wooding, J. M. 1996: Communication and Commerce along the Western Sealanes AD 400800, Oxford, Archaeopress CELTIC A 48 DAR 6. Anglo-Saxon Economics GW The seminar will begin with an overview of the key developments in Anglo-Saxon and Viking coinage, and of some of the main issues in the monetary history of the period, and the relationship between monetary history and broader economic history. The seminar will then focus on the use and interpretation of coins and other 'monetary' objects as sources, using case studies to explore some of the issues concerned. This is a selected bibliography with a focus on different approaches to the use of coins as evidence, and to economic history. More specific guidance can be provided on particular areas of coinage if required. J. Casey and R. Reece (eds), Coins and the Archaeologist, 2nd edition (London 1988), especially the papers by John Kent (Interpreting coin finds) and Marion Archibald (English medieval coins as dating evidence) [ISSUE DESK IOA CAS 1; INST ARCH KM CAS] B. Cook & G.Williams (eds), Coinage and History in the North Sea World, c. 500-1250 (Leiden 2006). Contains papers on a wide variety of Anglo-Saxon and Viking monetary topics. The articles by Richard Abdy and Gareth Williams are particularly important from a methodological perspective, as well as providing a major reinterpretation of coin use in the 5th-7th centuries. Alan Vince’s paper is a useful integration of archaeological and numismatic evidence [INST ARCH KM COO] J. Graham-Campbell & G. Williams (eds), Silver Economy in the Viking Age (Walnut Creek 2007). The papers in this volume provide a mixture of academic perspectives on coinage, bullion and status economies in the Viking Age, drawing on archaeology, history, numismatics and economic anthropology. The papers by the two editors provide overviews and critique of the subject as a whole [INST ARCH KM GRA] 9 A. Gannon, The Iconography of Early Anglo-Saxon Coinage, Sixth to Eighth Centuries (Oxford 2003). The most significant at historical study of the Anglo-Saxon coinage to date, with detailed comparisons between coins and designs in other media [INST ARCH KM GAN] F. Colman, Money Talks. Reconstructing Old English (Berlin/New York 1992). Still the only major study of coins as a source for the study of the English language D.M. Metcalf, An Atlas of Anglo-Saxon and Norman Coin Finds, 973-1086 (London 1998). Although some of the interpretations and conclusions are contentious (and rather more speculative than the author seems to acknowledge), this shows the sort of questions which can be asked of coinage as evidence [INST ARCH KM MET] M.A.S. Blackburn & D.N. Dumville (eds), Kings, Currency and Alliances: History and Coinage of Southern England in the Ninth Century (London 1998). The papers by Simon Keynes and Mark Blackburn on Alfred provide an excellent case-study on the use of coins together with other forms of historical evidence, but several of the other papers are also of interest [INST ARCH KM BLA] M.A.S. Blackburn (ed) Anglo-Saxon Monetary History (Leicester 1986). Useful papers on a variety of topics [INST ARCH KM BLA] J.J. North, English Hammered Coinage, Volume 1, Early Anglo-Saxon to Henry III, c. 6001272, 3rd edition (London 1994). Excellent type catalogue of coinage of the period, but with minimal interpretation R. Hodges, Dark Age Economics. The origins of towns and trade, AD 600-1000 (London 1982). Somewhat dated, but not yet superseded as the main economic text book for the early Anglo-Saxon period [INST ARCH DA 180 HOD] R. Samson, Social Approaches to Viking Studies (Glasgow 1991). Contains a number of interesting papers which cross the boundaries between archaeology, anthropology, economics and monetary history [SCANDINAVIAN A 13 SAM] 7. Anglo-Saxon Charters and Archaeology AR In the later Anglo-Saxon period it was common practice to produce written descriptions of the boundaries of estates. Such descriptions are often very detailed and the charters provide an invaluable source for the reconstruction of ancient landscapes. This seminar explores the scope and limitations of the evidence. Cited below is Sawyer's handlist; the first port of call in any research into the bounds. This volume has an index of places and provides bibliographies - you may find it interesting to see if any charters exist for areas with which you are familiar. Essential N. Brooks 1974 'Anglo-Saxon Charters: the work of the last twenty years', Anglo-Saxon England 3, 211-31 [INST ARCH PERS] D. Hooke 1998 The Landscape of Anglo-Saxon England (Chapters 3-5) [INST ARCH DAA 180 HOO] Recommended reading H. Finberg 1972 The Early Charters of the West Midlands (see p.184-96 - the Hallow Hawling charter) [HISTORY 27h FIN] A. Reynolds 2002 ‘Burials, Boundaries and Charters in Anglo-Saxon England: A Reassessment’, in S. Lucy and A. Reynolds (eds), Burial in Early Medieval England and Wales. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 17, 171-94 [INST ARCH DAA 180 LUC] M. Swanton (ed.) 1975 Anglo-Saxon Prose (see p.11-14 - Two Crediton Documents) [INST ARCH TEACHING COLLECTION 798; INST ARCH DAA 180 SWA] 10 T. Thompson 1959 'The Early Bounds of Wanborough and Little Hinton: an Exercise in Topography', Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine 57, 201-11 [INST ARCH PERS] For reference to individual charters the standard source is: P. Sawyer 1968 Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated List and Bibliography [INST ARCH DAA 180 SAW] This can also be found online: http://www.esawyer.org.uk 8. Landscapes of Warfare TW Warfare dominates the historical record of early medieval Britain, and yet the battlefields of the period are practically invisible from an archaeological pespective. This session will consider the reasons for this, and how multi-disciplinary approaches to landscapes of conflict can help to locate battlefields and illuminate social attitudes to violence. We will address the tension between functionalist approaches to military history, the potential of battlefield archaeology to uncover new evidence and the influence of anthropology and phenomenology on the study of conflict landscapes. Our evidence will consist of place-names, historical accounts, wider consideration of the historic environment and the circumstantial evidence for conflict, including military equipment, mass graves and weapon trauma. Essential G. Halsall 1989 ‘Anthropology and the Study of Pre-Conquest Warfare and Society’, in S.C. Hawkes (ed.) Weapons and Warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, 155-178 INST ARCH HJ HAW T. J. T. Williams, ‘Landscape and Warfare in Anglo-Saxon England and the Viking Campaign of 1006’ (Early Medieval Europe, forthcoming – to be supplied by author) Further Reading A. Andrén 2006 ‘A World of Stone: Warrior Culture, Hybridity, and Old Norse Cosmology’, in A. Andrén, K. Jennbert and C. Raudvere (eds), Old Norse Religion in Long-term Perspectives, 33-8 INST ARCH DAM 100 Qto AND; G. Foard and R. Morris, 2012 The Archaeology of English Battlefields: Conflict in the PreIndustrial Landscape, CBA Research Report 168 (esp. 45-51) INST ARCH DAA Qto Series COU 168 G. Halsall, 2003 Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West, 450-900 (esp. pp. 134 - 162 and 177 – 214) HISTORY 41 FA HAL R. Lavelle, 2011 Alfred's Wars: Sources and Interpretations of Anglo-Saxon Warfare in the Viking Age (esp. 264 – 314) NOT IN THE LIBRARY? L. Loe, A. Boyle, H. Webb and D. Score 2014 ‘Given to the Ground’: A Viking Age Mass Grave on Ridgeway Hill, Weymouth NOT IN THE LIBRARY? P. Morgan, 2000 ‘The Naming of Medieval Battlefields’ in D. Dunn (ed.), War and Society in Medieval and Early Modern Britain, 34-52 NOT IN LIBRARY? P. Marren, 2006 Battles of the Dark Ages NOT IN LIBRARY? A. Reynolds 2013 ‘Archaeological Correlates for Anglo-Saxon Military Activity in Comparative Perspective’, in J. Baker, S. Brookes and A. Reynolds (eds), Landscapes of Defence in Early Medieval Europe, 1-38 NOT IN LIBRARY? S. Semple, 2013 Perceptions of the Prehistoric in Anglo-Saxon England: Religion, Ritual, and Rulership in the Landscape, 74-99 INST ARCH DAA 180 SEM (available online) 11 9. Political and Administrative Landscapes AR This session considers how an interdisciplinary approach can be taken to reconstructing governance and authority in the Anglo-Saxon Landscape. Themes covered include law, justice and civil defence. Essential A. Reynolds 1999 Later Anglo-Saxon England: Life & Landscape (chapter 3, 65-110) [ISSUE DESK IOA DAA 180 REY; INST ARCH DAA 180 REY] Case studies J. Baker and S. Brookes 2013 Beyond the Burghal Hidage: Anglo-Saxon Civil Defence in the Viking Age. INST ARCH DAA 180 BAK S. Driscoll and M. Nieke (eds) 1988 Power and Politics in Early Medieval Britain and Ireland (good topical case studies). INST ARCH DAA 180 DRI; CELTIC A 45 DRI D. Hill and A. Rumble (eds) 1996 The Defence of Wessex: The Burghal Hidage and AngloSaxon Fortifications. INST ARCH DAA 180 HIL A. Reynolds 2009 Anglo-Saxon Deviant Burial Customs (esp. chapters 4, 5 and 6)(available online). INST ARCH DAA 180 REY A. Reynolds and S. Brookes 2013 ‘Anglo-Saxon Civil Defence in the Localities: A CaseStudy of the Avebury Region’, in A. Reynolds and L. Webster (eds), Early Medieval Art and Archaeology in the Northern World: Studies in Honour of James Graham-Campbell, 561-606 INST ARCH DA 180 REY S. Semple and A. Pantos (eds) 2004 Assembly Places and Practices in Early Medieval Europe (good comparative case-studies). INST ARCH DA 180 PAN 10. Student Presentations AR 11. Cremation in the Early Anglo-Saxon Period SH Cremating the dead formed a major role in the funerary rites of Early Anglo-Saxon England. This session explores the range of materials found with cremation burials, the containers in which such remains were often placed and the nature of the cremation process. Essential: it is important that you read the following general surveys: C. Wells 1960 A study of cremation, Antiquity, 34, 29-37 [INST ARCH PERS] J. McKinley 1994 Spong Hill Part VIII: The Cremations, East Anglian Archaeology, 69 [ISSUE DESK IOA EAA 69] And select from the following more detailed studies: J. M. Bond 1996 Burnt offerings: animal bone in Anglo-Saxon cremations, World Archaeology, 28 (1), 76-88 [INST ARCH PERS] S. Carnegie & W. Filmer-Sankey 1993 A Saxon 'Cremation Pyre' from the Snape AngloSaxon Cemetery, Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, 6, 107-111 [INST ARCH DAA 180 ANG] J. D. Richards, 1987 The Significance of Form and Decoration of Anglo-Saxon Cremation Urns, BAR British series, 166 [INST ARCH DAA Qto Series BRI 166] T. Oestigaard 1999 Cremations as transformations, European Journal of Archaeology, 2 (3), 345-64 [INST ARCH PERS] 12 H. Williams 2002 ‘Remains of Pagan Saxondom’? – the study of Anglo-Saxon cremation rites, in Burial in early medieval England and Wales, eds. S. Lucy & A. Reynolds, 47-71 [INST ARCH DAA 180 LUC] Do follow up any references or topics you think might be of value to the seminar – you will be expected to contribute fully at each meeting. 12. Inhumation in the Early Anglo-Saxon Period SH This session explores the rite of inhumation burial in Early Anglo-Saxon society and examines the variety of materials found with such burials and the nature of the cemeteries within which they occur. Further topics to be considered include grave elaboration and the means by which cemetery data can be analysed. Essential: it is important that you read the following general surveys: H. Härke 1997 Early Anglo-Saxon Social Structure, in The Anglo-Saxons from the migration period to the eighth century : an ethnographic perspective, ed. J. Hines, 125-70 [INST ARCH DAA 180 HIN] C. A. Roberts, F. Lee & J. Bintliff 1989 Burial Archaeology: Current Research, Methods and Developments, BAR British series, 211: relevant papers [INST ARCH DAA Qto Series BRI 211] And select from the following more detailed studies: A. C. Hogarth, 1973 Structural features in Anglo-Saxon graves, Archaeological Journal, 130, 1973, 104-19 [INST ARCH PERS] N. Reynolds 1976 The structure of Anglo-Saxon graves, Antiquity, 50, 140-4 [INST ARCH PERS] J. Huggett 1996 Social analysis of Early Anglo-Saxon inhumation burials: archaeological methodologies, Journal of European Archaeology, 4, 337-65 [INST ARCH PERS] N. Stoodley 1999 The Spindle and the Spear. A critical enquiry into the construction and meaning of gender in the Early Anglo-Saxon burial rite, BAR British Series, 288 [INST ARCH DAA Qto Series BRI 288] S. Crawford 1999 Childhood in Anglo-Saxon England [INST ARCH DAA 180 CRA; HISTORY 27 h CRA] S. Crawford 1997 Britons, Anglo-Saxons and the Germanic Burial Ritual, in Migrations and Invasions in Archaeological Explanation, eds. J. Chapman and H. Hamerow, BAR International series, 664, 45-72 [INST ARCH BD Qto CHA] S. Lucy 1998 The Early Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries of East Yorkshire, BAR British Series, 272 [INST ARCH DAA Qto Series BRI 272] M. Harman & others 1981 Burials, bodies and beheadings in Romano-British and AngloSaxon cemeteries, Bulletin of the British Museum Natural History (Geology), 35, 145-88 [STORES PERS] Do follow up any references or topics you think might be of value to the seminar – you will be expected to contribute fully at each meeting. 13. The Geography of Anglo-Saxon Burial This session considers how a landscape approach can facilitate a much deeper understanding of Anglo-Saxon society and landscape. Moving away from traditional approaches focussing on material culture we will consider in depth methodological approaches. 13 Essential A. Reynolds 2009 Anglo-Saxon Deviant Burial Customs (chapter 5)(available online). INST ARCH DAA 180 REY H. Williams 2006 Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain (chapter 6). INST ARCH DAA 180 WIL 14. Burial Practice: the ‘Final Phase’ and ‘Conversion Period’ CS Changes in burial practice during the later 6th and 7th centuries culminated in the abandonment of formal furnished inhumation. Graves of this period have been characterized as representing a ‘Final Phase’ (of Furnished Burial), and the changes attributed to a range of causes including conversion to Christianity and cultural alignment with the Merovingian continent. In this session we consider the evidence in the light of recent research and against the longer-term perspective of Anglo-Saxon mortuary practice from the 6th to the 9th centuries. How useful are the terms used to describe 7th-century burial practices? Essential J. Hines and A. Bayliss (eds) 2013 Anglo-Saxon Graves and Grave Goods of the 6th and 7th centuries AD: a Chronological Framework. Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 33. Chapters 1, 8 and 10. INST ARCH DAA 180 Qto BAY Some Key Studies and Sites A. Boddington 1990 Models of burial, settlement and worship: the Final Phase reviewed, in E. Southworth (ed), Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries: A Reappraisal, 177-99. [DAA 180 SOU] J. Blair 2005 The Church in Anglo-Saxon society. Oxford: OUP. esp pp 228-240) INST ARCH DAA 180 BLA; HISTORY 27 E BLA D. Hadley 2011 Late Saxon burial practice, in H. Hamerow, D. Hinton and S. Crawford (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology, 289-311. Oxford: OUP. INST ARCH DAA 180 HAM H. Geake 1997 The use of grave-goods in Conversion-period England, c.600-c.850. Oxford: BAR Brit. Ser. 261 [DAA Quarto Series BRI 261] M. Hyslop 1963 Two Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries at Chamberlains Barn, Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, Archaeological Journal 120, 161-200 (available online) IOA PERS E. T. Leeds 1936 The Final Phase, in E. T. Leeds, Anglo-Saxon Art and Archaeology, 96-114. Oxford: OUP. [DAA 180 LEE] A. Meaney and S. Hawkes 1970 Two Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries at Winnall, Winchester, Hampshire. Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 4 [DAA 410 H2 MEA] C. Scull 2009, Early Medieval (late 5th-early 8th centuries) Cemeteries at Boss Hall and Buttermarket, Ipswich, Suffolk. Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph 27. INST ARCH DAA 410 Qto SCU C. Scull and A. Bayliss 1999 Dating burials of the seventh and eighth centuries: a case-study from Ipswich, Suffolk, in J. Hines, K. Hølund Nielsen and F. Siegmund (eds) The pace of change: studies in early medieval chronology, 80-88. Oxford: Oxbow. INST ARCH DA Qto HIN M. Welch 2011 The Mid Saxon ‘Final Phase’, in H. Hamerow, D. Hinton and S. Crawford (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology, 266-287. Oxford: OUP. INST ARCH DAA 180 HAM B. Yorke 2006 The conversion of Britain: religion, politics and society in Britain c. 600-800. London: Longman. INST ARCH DAA 180 YOR; HISTORY 27 E YOR 15. The Conversion to Christianity in Britain BY 14 This session will consider issues involved in studying the conversion to Christianity in different areas of Britain in the period c.400-700. In particular it will provide an opportunity to explore the problems in bringing written and archaeological sources together, and the question of whether their different approaches can be reconciled. Whether burial practices are indicative of religious belief is a key issue, and one where comparison between different areas of Britain may be particularly valuable. Essential reading A. Boddington 1990, ‘Models of burial, settlement and worship: the final phase reviewed’, in Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries; A Reappraisal, ed. E. Southworth 177-99 DAA 180 SOU S. Church 2008, ‘Paganism in Conversion-Age Anglo-Saxon England: the evidence of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History reconsidered’, History, 93, 162-80 HISTORY PERS (available online) A. Maldonado 2013, ‘Early medieval burial in Scotland: new questions’, Medieval Archaeology 57, 1-34 INST ARCH PERS (available online) Recommended Reading A. Bayliss, J. Hines, K Høilund Nielsen, G. McCormac and C. Scull (2013) Anglo-Saxon Graves and Grave Goods of the Sixth and Seventh Centuries AD: a Chronological Framework INST ARCH DAA 180 Qto BAY J. Blair 2005, The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society (ch. 1-4) INST ARCH DAA 180 BLA; HISTORY 27 E BLA M. Carver 2003, The Cross Goes North. Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300-1300 (especially Pluskowski and Patrick, Petts, Turner and Yorke) INST ARCH DA 180 CAR B. Colgrave and R. Mynors (eds) 1969, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (alternatively, Penguin classics or Everyman translations) HISTORY 27 H BED M. Dunn 2009, The Christianisation of the Anglo-Saxons NOT IN LIBRARY? N. Edwards (ed.) 2009, The Archaeology of the Early Medieval Celtic Churches (especially Introduction, Longley, O’Brien and Hall) INST ARCH DAA 190 EDW H. Geake 1997, The Use of Grave-goods in Conversion-Period England c. 600-c.850 (BAR British series 261) INST ARCH DAA Qto Series BRI 261 J. Hines 1997, ’Religion: the limits of knowledge’, in The Anglo-Saxons From the Migration Period to the Eighth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective, ed. J. Hines, 375-410 INST ARCH DAA 180 HIN S. Lucy and A. Reynolds, (eds) 2002, Burial in Medieval England and Wales INST ARCH DAA 180 LUC B.A.E. Yorke 2006, The Conversion of Britain 600-800 INST ARCH DAA 180 YOR; HISTORY 27 E YOR 16. Art and Society in Anglo-Saxon England, c. 600-1100 JK This session considers the contribution of art historical approaches to the study of AngloSaxon cultural life. Essential J. Graham-Campbell, 2013 Viking Art. INST ARCH DA 181 GRA L. Webster 2012 Anglo-Saxon Art: A New History. INST ARCH DAA 180 WEB Individual sources and case studies J. Backhouse, The Lindisfarne Gospels (1981) [IA DAA 410 N.7 BAC] 15 R. J. Cramp, British Academy Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture (general introduction and various county-based volumes) [IA DAA 180 COR] J. Hawkes, The Sandbach Crosses. Sign and significance in Anglo-Saxon sculpture (2002) INST ARCH DAA 180 HAW J. Hawkes & S. Mills, Northumbria's Golden Age (1999) [IA DAA 180 HAW] G. Henderson, From Durrow to Kells, the insular manuscripts from the 6th to the 9th century (1987) [IA DAA 180 HEN] C. E. Karkov, The Art of Anglo-Saxon England (2011) [INST ARCH DAA 180 KAR] C. Karkov & R. Farrell, Studies in Insular Art and Archaeology American Medieval Studies 1 (1990) [DA 190 KAR] M. Redknap, N. Edwards et al., Pattern and Purpose in Insular Art (2001) [IA DAA 180 QTO RED] M. Spearman & J. Higgitt, The Age of Migrating Ideas (1993) [IA DAA 190 QTO SPE] G. Thomas, ‘Carolingian Culture in the North SeaWorld: Rethinking the Cultural Dynamics of Personal Adornment in Viking-age England’, European Journal of Archaeology 2012, 15 (3), 486-518 (available online) L. Webster, ‘Style: Influences, Chronology and Meaning’, in H. Hamerow, D. Hinton and S. Crawford (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology (2011), 460-500 INST ARCH DAA 180 HAM L. Webster & J. Backhouse, The Making of England, Anglo-Saxon Art and Culture AD 600900 (1992). [DAA 180 WEB] L. Webster & M. Brown, The Transformation of the Roman World (1997) [ISSUE DESK IOA WEB 2; INST ARCH DA 180 WEB] D. Wilson, Anglo-Saxon Art (1984) [INSTARCH DAA 180 WIL] S. Youngs, The Work of Angels (1990) [ISSUE DESK / IA DAA 180 BRI] 17. Viking settlement JK This session considers the range of evidence for Viking settlement in the Northern Isles and the wider North Atlantic from around AD 800 onwards. Among topics for discussion are the question of dating, what characterises a Viking settlement and settlement patterns. Essential Fitzhugh, W.W. et al. (eds) 2000. Vikings. The North Atlantic Saga, esp. Introduction and chapters 8 - 11 [INST ARCH DA 181 FIT; MAIN SCANDINAVIAN QUARTOS A 13 FIT] Barrett, J.H. 2003. Culture Contact in Viking Age Scotland. In J.H. Barrett (ed). Contact, Continuity and Collapse: the Norse Colonization of the North Atlantic, 73-112. [ISSUE DESK IOA 3500; MAIN SCANDINAVIAN A13 BAR]. Myhre, B. 1998. The Archaeology of the Early Viking Age in Norway. In H.B. Clarke, M.N. Mhaonaigh and R. Ó Floinn (eds) Ireland and Scandinavia in the Early Viking Age, 3-36. [ISSUE DESK IOA 3501; INST ARCH DAA 700 CLA; CELTIC N 88 CLA]. Recommended reading Ashby, S. P. 2009 ‘Combs, contact and chronology: Reconsidering hair combs in earlyhistoric and Viking-Age Atlantic Scotland’, Medieval Archaeology 53, 1-33 INST ARCH PERS (available online) Arge, S.W. et al. 2005. Viking and medieval settlement in the Faroes: people, place and environment. Human Ecology 33, 597-620 [GEOGRAPHY PERS; also available as an electronic journal]. Árný Sveinbjörnsdóttir et al. 2004. 14C dating of the settlement of Iceland. Radiocarbon 46 (1): 387-394. [INST ARCH PERS; also available as an electronic journal]. 16 Barrett, J.H. (ed) 2003. Contact, continuity and collapse. [MAIN SCANDINAVIAN A13 BAR]. Dugmore, A.J. et al. 2000. Tephrochronology, Environmental Change and the Norse Settlement of Iceland. Environmental Archaeology 5, 21-34. [INST ARCH PERS; also available as an electronic journal]. Dugmore, A.J. et al. 2005. The Norse landnám on the North Atlantic islands: an environmental impact assessment. Polar Record 41 (216), 21-37. [GEOSCIENCE PERS; also available as an electronic journal]. Graham-Campbell, J. & C. Batey 1998. Vikings in Scotland [INST ARCH DA 500 GRA]. Hadley, D.M. 2006. The Vikings in England: Settlement, society and culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press HISTORY 27 H HAD Hadley, D.M. & J.D. Richards. (eds.) 2000. Cultures in Contact: Scandinavian settlement in England in the ninth and tenth centuries. Turnhout: Brepols INST ARCH DAA 181 HAD Hines, J. et al. (eds) 2004. Land, Sea and Home. Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph Series, Vol. 20 [INST ARCH DA 181 FIT]. Myhre, B. 1993. The beginning of the Viking Age – some current archaeological problems. In A. Faulkes and R. Perkins (eds) Viking revaluations: Viking Society Centenary Symposium, 14 – 15 May 1992, 182-216. Birmingham: Viking Society for Northern Research. [INST ARCH DA 181 FAU; MAIN ICELANDIC A 8 VIK]. Olsson, I.U. 2006. Comments on Sveinbjörnsdóttir et al. (2004) and the settlement of Iceland. Radiocarbon 48 (2): 243-252. [INST ARCH PERS; also available as an electronic journal]. Roesdahl, E. 1991. Revised Penguin paperback 1998. The Vikings. [SCANDINAVIAN A13 ROE; INST ARCH DA 181 ROE]. Vésteinsson, O. 1998. Patterns of settlement in Iceland: a study in pre-history. Saga-book Vol. XXV, part 1, 1-29 [MAIN SCANDINAVIAN PERS]. 18. Anglo-Saxon and Medieval London: Continuity and Change JC This session will consider how archaeological research over the last fifty years has transformed our understanding of the development of London and the lives of its people, in a period of dramatic change between the 7th century and the 15th century. It will also demonstrate how much the study of artefacts, their development and distribution, can contribute to the overall picture. Overviews Museum of London Archaeology Service 2000 The Archaeology of Greater London: An assessment of archaeological evidence for human presence in the area now covered by Greater London (chapters 8 (R. Cowie & C. Harding) and 9 (B. Sloane et al)) London: Museum of London Archaeology Service [ISSUE DESK IOA MUS] J. Schofield 2011 London, 1100-1600: The archaeology of a capital city Sheffield: Equinox [INST ARCH DAA 416 SCH] A. Vince 1990 Saxon London: an archaeological investigation London: Seaby [INST ARCH DAA 416 VIN] R. E. M. Wheeler 1935 London and the Saxons (Preface and Introduction) London: London Museum [UCL Main Library: LONDON HISTORY 70.600 LON] Individual topics and site reports D. Bowsher et al 2007 The London Guildhall: An archaeological history of a neighbourhood from early medieval to modern times London: Museum of London Archaeology Service [INST ARCH DAA 416 Qto BOW pt 1 & pt. 2] 17 R. Cowie & L. Blackmore et al 2012 Lundenwic: Excavations in Middle Saxon London, 1987–2000 London: Museum of London Archaeology Service [INST ARCH DAA 416 Qto COW] G. Egan & F. Pritchard 1991 (repr 2002, 2008) Dress Accessories, c. 1150- c. 1450: Medieval Finds from Excavations in London 3 London: HMSO; repr Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer [INST ARCH HD EGA] I. Grainger et al 2008 The Black Death Cemetery, East Smithfield, London London: Museum of London Archaeology Service [INST ARCH DAA 416 Qto GRA] J. Haslam 2010 ‘King Alfred and the development of London’ London Archaeologist 12.8, 208-12 [INST ARCH Pers; Online: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/london_arch/contents.cfm?vol=12:08] J. Pearce & A. Vince 1988 A Dated Type-Series of London Medieval Pottery, Part 4: Surrey Whitewares London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society [INST ARCH DAA 416 PEA] A. G. Vince 1985 ‘The Saxon and medieval pottery of London: a review’ Medieval Archaeology 29, 25-93 [Online: http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/med_arch/contents.cfm?vol=29] A. G. Vince (ed) 1991 Aspects of Saxo-Norman London 2: Finds and environmental evidence London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society [INST ARCH DAA 416 VIN] 19. Student Presentations and Course Review AR 20: British Museum Visit: Sutton Hoo, Broomfield, Taplow, etc. AR This museum visit considers the finds from one of the most important archaeological discoveries – the Sutton Hoo ship-burial – and examines material from comparable burials, most notably that from Taplow. Essential: it is important that you read the following general survey: M. Carver 1998 Sutton Hoo: Burial Ground of Kings? INST ARCH DAA 410 S.7 CAR And select from the following more detailed studies: M. Müller-Wille 1974 Boat-graves in northern Europe, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration, 3, 187-204 INST ARCH PERS R. Bruce-Mitford (3 vols. 1975, 1978 & 1983) The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial INST ARCH DAA 410 Qto BRU M. Carver 2005 Sutton Hoo: A seventh-century princely burial ground and its context INST ARCH DAA 410 Qto CAR L. Webster 1992 Death’s Diplomacy: Sutton Hoo in the light of other male princely burials, in R. Farrell & C. Neuman de Vegvar (eds), Sutton Hoo: Fifty Years After, 75-81 ISSUE DESK IOA FAR 1 W. Filmer-Sankey and T. Pestell 2001 Snape Anglo-Saxon Cemetery: excavation and surveys 1824-1992, East Anglian Archaeology 95 INST ARCH DAA Qto Series EAA 95 S. Hirst & others 2004 The Prittlewell Prince: the discovery of a rich Anglo-Saxon burial in Essex INST ARCH DAA 410 E.7 HIR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Libraries and other resources In addition to the Library of the Institute of Archaeology, other libraries in UCL with holdings of particular relevance to this degree are: the Main Library and the DMS Watson 18 science library. The early and later medieval galleries at the British Museum both contain material relevant to the course as does the Museum of London. Information for intercollegiate and interdepartmental students Students enrolled in Departments outside the Institute should obtain the Institute’s coursework guidelines from Judy Medrington (email j.medrington@ucl.ac.uk), which will also be available on the IoA website. INSTITUTE OF ARCHAELOGY COURSEWORK PROCEDURES General policies and procedures concerning courses and coursework, including submission procedures, assessment criteria, and general resources, are available in your Degree Handbook and on the following website: http://wiki.ucl.ac.uk/display/archadmin. It is essential that you read and comply with these. Note that some of the policies and procedures will be different depending on your status (e.g. undergraduate, postgraduate taught, affiliate, graduate diploma, intercollegiate, interdepartmental). If in doubt, please consult your course co-ordinator. 19