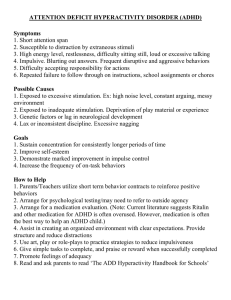

- 97 - deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children were developed by

advertisement